Little Italy's Last Stand

Twenty-five years later, Martin Scorsese's 'Mean Streets' is still the definitive take on New York lowlifes

MORE THAN the autobiography of a filmmaker, the 1973 Mean Streets is a biography of a way of life, and then-30-year-old director Martin Scorsese could tell this way of life was already on its way out.

The Manhattan neighborhood where the demigangsters of Mean Streets hang out shrinks before the lens. Filmmakers sentimentalize Little Italy--which can appear pleasant, as in Moonstruck--but Mean Streets depicts the neighborhood as a red-lighted terrarium. The overgrown boys inside this bubble don't have any idea of how to live outside of it.

Mean Streets, which is being rereleased on its 25th anniversary, is essentially a four-person drama about petty and, on the whole, nonviolent criminals. Harvey Keitel plays Charlie, a haunted Catholic, skeptical of priests and yet afraid of hellfire. (As a reminder of the torments that might be his, he dips his hands into flame; Scorsese probably borrowed the idea from Kirk Douglas' Van Gogh in Lust for Life.) "St. Charles" he's called by one pal.

Charles is a numbers runner whose professionalism will be, he hopes, rewarded by his uncle, a local Mafioso named Giovanni (Cesare Danova). Unfortunately for his ambitions, Charlie is tangled up with people Giovanni considers unsuitable: his pretty cousin Teresa (Amy Robinson), who has epilepsy, and Johnny Boy, a self-destructive wise ass played by Robert De Niro.

Scorsese introduces De Niro's character in the act of blowing up a U.S. mailbox for laughs. Of all of the wastrels we see here, Johnny Boy is the only one who really enjoys himself, who doesn't care about "respect" as an abstract concept.

Charles, who has a St. Francis complex, thinks he can save Johnny from the consequences of his irresponsibility. Johnny owes money to every loan shark in town, including the intimidating Michael (Richard Romanus, who looks like a model of Ray Liotta carved by an art-deco sculptor). Michael, tired of being cheated, is ready to break Johnny's legs for him. The problem pinions the guilty Charles between his own ambitions and his duty to his friend.

EARLY ON, Scorsese was using all of the devices that mark him today. There are the long tracking shots--a fight in a pool hall slides along all four walls; Charlie meets his buddies at Volpe's topless joint and the camera follows him as faithfully as a dog--and the soundtrack is loaded with barroom music: the Stones, Phil Spector and Italian tunes when the night gets old.

In the dialogue, too, there is much that was to be copied by writers about tough guys in the next 25 years, especially the repetition and echolalia ("What's the matter with you?" "Yeah, what's the matter with you?"). Too often, as in David Mamet, this kind of talk sounds like blowhardism; here, it is mint-fresh, even the slang.

In one scene, the Robbie Coltraneish actor George Mannoli razzes the bunch as "mooks," a potentially made-up word that New Yorkers and fake New Yorkers have been using ever since. Even the greeting the criminals use--a drawled-out "Aaaaaaaaay!"--got picked up. Henry Winkler, debuting an Italianoid character named Fonzarelli on TV's Happy Days the year after Mean Streets, made the exclamation nationally famous. A few moments, however, are dated, particularly a fag joke that pegs the movie as an oldster.

Still, this hugely influential film sired Trainspotting and Pulp Fiction alike. But like all great originals, it's undiminished by copying. It has corridors and crannies still worth exploring. Charlie delivers a telling monologue on the beach about what he likes in life (movies, chicken with lemon and garlic) and what he hates (the beach, the sun). In one significant scene, we see the Don, Uncle Giovanni, being approached by one of his clients, asking him politely, "May I sit? May I talk?" The calm lunacy that made De Niro famous begins here; his character is given to flamboyant gestures: he uses the light atop the Empire State Building as target practice for his .38.

It's a dark film, but Scorsese is affectionate about the conceits of these would-be hoodlums--hijackers of worthless objects, connivers at $15 hustles. In many scenes, the tone is as light as in Scorsese's dark comedy After Hours. But Mean Streets is also a farewell to youth. Scorsese knew what the fate of these mooks would be.

Keitel's Charlie, drunk in an Italian graveyard, listens to the raucous partying of some Puerto Ricans; it's a new society beyond his tribe, encroaching on the boundaries of his neighborhood. It's a glimpse of a world bigger than the couple of bars and restaurants he calls home.

For the time being at least, Charlie and his friends can squabble, get drunk, hustle, wait for favors and stare at women without much of an idea how to pick them up or how to keep them once they are picked up.

It's one of the most devastating satires ever made in America, and yet it's so warmhearted! In it are the seeds that earned Scorsese his reputation as our most important director, the roots that lead directly to Taxi Driver and Raging Bull, the tropes that inspired his disciples, from Spike Lee to Quentin Tarantino, who spread his ideas to millions.

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![]()

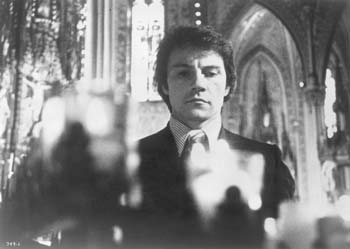

St. Charlie: Harvey Keitel's Charlie wrestles with his ambition and his duty in 'Mean Streets.'

Mean Streets (1973; R; 110 min.), directed by Martin Scorsese, written by Scorsese and Mardik Martin, photographed by Kent Wakeford and starring Robert De Niro and Harvey Keitel.

From the April 9-15, 1998 issue of Metro.

![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)