![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

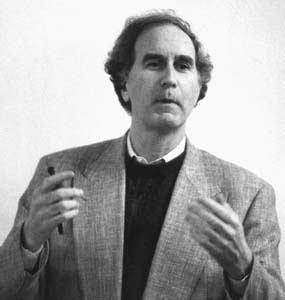

My Way: Though he says he's never had a problem with McEnery, Mayor Ron Gonzales has eliminated the last vestiges of McEnery's power structure at City Hall and taken the city in a regional direction which has left the downtown-centric Mayor Emeritus on the outs.

My Way: Though he says he's never had a problem with McEnery, Mayor Ron Gonzales has eliminated the last vestiges of McEnery's power structure at City Hall and taken the city in a regional direction which has left the downtown-centric Mayor Emeritus on the outs.

Photograph by Chuck Savadelis

The Ron & Tom Wars The ripples of the feud between Mayor Past and Mayor Present have spread across people and projects, in a power shift that has been at times painful. Will Ron and Tom ever get along? Some say this town's just not big enough for the both of them. By Will Harper IT WAS A NIGHT RON GONZALES will never forget. Several thousand citizens sat packed in rows of chairs to hear his second annual state-of-the-city address. And former San Jose mayor Tom McEnery seemed to be everywhere, even if no one actually saw him. The evening's main event, Gonzales' mayoral speech, was held at the former mayor's namesake, the San Jose McEnery Convention Center. After the event, the city's political glitterati traveled four blocks north to celebrate at San Pedro Square, which is owned by the McEnery family--complete with a dinner party in the carnivorous Blake's, one of McEnery's favorite hangouts. But the Blake's regular was not at his usual spot that night. The surrounding landscape was littered with landmarks of the McEnery era: Just down the road to the west loomed the San Jose Arena, a facility that owes its existence to McEnery's decision to flex his political muscle in the late 1980s. To the southeast stood the Fairmont Hotel, the anchor of McEnery's efforts to rebuild the downtown in the '80s. And, of course, there was the convention center, the place where everyone had been earlier in the evening and where McEnery himself had delivered his final address after eight years of mayoral power. But this wasn't Tom McEnery's night. In Gonzales' 45-minute talk about grand visions for the nation's 11th-largest city, McEnery's name never even came up. By most accounts, Gonzales' second annual state-of-the-city speech on Feb. 17 was a resounding triumph. Gonzales, McEnery's second successor, had scored a major political coup by getting Gov. Gray Davis and U.S. Sen. Dianne Feinstein--both of whom made videotaped appearances--to promise money and other support to bring BART to San Jose. Only a few years ago, the idea of bringing the rail passenger service to San Jose seemed impossible. But using the bully pulpit of the mayor's office--something McEnery knows plenty about--Gonzales willed the issue back to the political centerstage. Former Mayor Susan Hammer attended, and she was acknowledged for her efforts in forging the deal for the city's new library with San Jose State University. McEnery says he can't quite remember why he didn't go this year. Of course, it might have been because the invitations to Mayor Ron Gonzales' first state-of-the-city speech in February 1999 omitted his name. The site of the annual event was listed as the "San Jose Convention Center," conspicuously leaving out the word "McEnery." At the time, a mayoral aide explained the error as a "rookie mistake." But "rookie mistake" or not, some say it's one of many slights, large and small, which have contributed to a full-blown and visible rift between Mayor Present and Mayor Past. McEnery knows one thing for sure: He doesn't want to talk about it. Asked if he thinks Gonzales is pursuing a political vendetta, McEnery will only say cryptically, "Being in the mayor's office isn't about petty feuds or an enemies list. It involves doing good things for the community and making people's lives better. "I wish them [the Gonzales administration] well in discerning that simple fact. I hope they're successful." IN THE BRAND-NEW BIBLIOTECA Latinoamericana, 40 first-graders brought in from Washington Elementary School listen attentively as a husky Latino man in business attire reads to them from Pip's Magic, a story about overcoming fear of the dark. Camera crews from KGO and KNTV capture the moment. To add a touch of informality, the reader, 48-year-old Mayor Ron Gonzales, takes off his charcoal blazer--a nice visual for the cameras. The mayor is showcasing a new program designed to place library cards in the hands of an estimated 23,000 first- and second-graders by May 2001. While McEnery, age 54, was a master of the sweeping gesture--such as kicking off a sports arena campaign with cheerleaders--Gonzales boasts a more Clintonian touch for the mundane: fixing sidewalks, painting over graffiti and distributing library cards to schoolkids. When Gonzales finishes the book, he replaces his coat and heads out a side door with bodyguard Chris Galios to the parking lot, where his government-issued black Lincoln Town Car awaits. He is heading back to City Hall, where he'll begin preparing for the monthly board meeting of the Valley Transportation Authority. Gonzales stops to answer a question about the perceived feud between him and McEnery: "Would you consider Tom to be a gracious ex-mayor?" "I'm in no position to evaluate that," the mayor replies. "Would you invite Tom over for dinner?" The mayor pauses, and then awkwardly answers that he doesn't invite anyone over to his house for dinner. "I've never had a problem with Tom," the mayor insists.

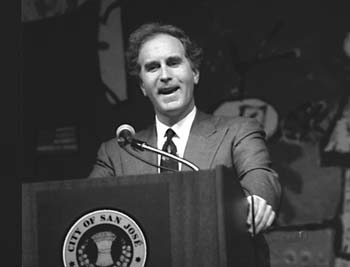

Public McEnemy: Former Mayor Tom McEnery earned a reputation during his City Hall tenure from 1983 to 1991 for punishing nagging council members and out-of-favor home developers. Since the election of San Jose Mayor Ron Gonzales, McEnery has been on the receiving end of rejection from City Hall. BUT EVEN GONZALES' pals find that statement hard to believe. County Assessor Larry Stone, a longtime Gonzales ally, says, "I like Tom, but I don't think Ron does." "I don't know if I'd go so far as to call it a grudge," Stone adds. "There is certainly more than a mild amount of tension between them." Longtime South Bay political operative Rich Robinson observes, "It's obvious that there's no love lost between the two. There may not be outright animosity, but there's certainly an indifference as to what the other guy's opinions are." "I don't think they have breakfast or lunch together," suggests beer distributor Mike Fox Sr., a friend and past supporter of both politicians. Although most insiders agree that a rift exists between Gonzales and McEnery, not everyone agrees as to who is to blame for the bad blood. "There's a tension that exists on the part of Tom," Fox says. "Ron, as mayor, is in the driver's seat." But a McEnery sympathizer, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, believes Gonzales is the source of friction. "A feud takes two people," the McEneryite says, "and I'm fairly certain that Tom McEnery is not too concerned about ... the mayor. Tom's doing his own thing." THE FIRST SIGNS OF A RIFT between the two politicians surfaced as far back as 1988, when McEnery was still mayor and Gonzales, then a member of the Sunnyvale City Council, was running for county supervisor against Milpitas Mayor Bob Livengood. McEnery backed Livengood. Gonzales later groused that he didn't have a chance to make his pitch to the former mayor before McEnery lent his imprimatur to Livengood. After being elected supervisor, Gonzales complained that he tried for three months to schedule a sit-down with McEnery, without success. The relationship continued to cool, sources say, when Gonzales backed Pete Carrillo over McEnery protégé David Pandori for the downtown City Council seat in 1990. But, by 1994, circumstances changed. Ex-Mayor McEnery was now running for Congress in the Democratic primary against then-Supervisor Zoe Lofgren. At the time, Mike Fox Sr. lobbied Gonzales, a notorious robo-campaigner, to get behind Fox's old friend McEnery, a fellow alum from San Jose's prestigious Bellarmine Preparatory School. Fox, who is also known for his formidable fundraising skills, even sweetened the deal for Gonzales, who by then had moved from Sunnyvale to San Jose with an eye on the mayor's seat. "I told Ron, 'If you back Tom, I'll see to it that I support you should you decide to run for mayor.' " So, in spite of his past clashes with the former mayor, Gonzales became a McEnery man. "Ron worked like a Trojan for McEnery," Fox recalls. "Ron was at campaign headquarters many days making phone calls, raising money." The circumstances around Gonzales' unexpected conversion have become part of San Jose political lore. One of the more popular theories--denied by all the parties involved--involves a quid pro quo in which McEnery promised to back Gonzales for mayor in exchange for his help on the congressional campaign. Fox says he knows of no such deal and suggests that gossip perhaps confused Fox's own promise of supporting Gonzales for mayor as being a promise made by McEnery himself. Regardless, to nearly everyone's surprise, frontrunner McEnery lost to Lofgren. Two years later, McEnery's name began surfacing as a possible mayoral contender in 1998. In a Mercury News story--which Gonzales advisers believed either McEnery or an ally planted--McEnery wouldn't rule out trying to get his old job back, saying, "I haven't made any decision about what I'm going to do." In that same story, a McEnery loyalist took an anonymous potshot at Gonzales, who spent most of his life in Sunnyvale before moving to San Jose in 1992: "There's no way Tom is going to sit back and see the mayor of Sunnyvale become the mayor of San Jose." McEnery ultimately didn't run. But McEnery did the next worst thing from Gonzales' standpoint: He backed the future mayor's opponent, City Councilwoman Pat Dando, a former aide to McEnery. "I think he [Gonzales] felt betrayed that Tom didn't support him for mayor," says Stone, who adds sympathetically, "but asking Tom not to support Pat Dando is like asking me not to support Ron Gonzales. They used to work together, and they're close friends."

State of Grace: Mayor Ron Gonzales, at his swearing-in ceremony with predecessor Susan Hammer (left), denies that McEnery is on an enemies list. His chief of staff Jude Barry says, 'If there's an enemies list, it's in some old filing cabinet left over from the McEnery administration.' GONZALES GOT HIS FIRST chance to flex some new mayoral muscle in June, during his first budget process as mayor. The mayor and his staff balked at a recommendation by departing Redevelopment Director Frank Taylor--a Hayes appointee who survived the McEnery and Hammer administrations--to boost the public subsidy from zero to $808,000 to renovate a decrepit green downtown apartment building owned by Dr. James Eu, says the mayor's budget director, Joe Guerra. One project detail that caught the attention of the mayor's budget expert: a $46,000 line item for development management, which was being handled by San Pedro Square Properties, a company run by John McEnery IV, Tom's nephew. (As it turns out, records show, Taylor also quietly awarded a $30,000 contract to San Pedro Square Properties to evaluate development proposals on the block where the Eu building stands.) After several months of haggling, the mayor and the City Council ultimately rescinded earlier offers to help fix up the building. David Eu, the building owner's son, later blamed the deal's demise on Gonzales' grudge against Tom McEnery. The mayor simply says he rejected the project because it was a "bad deal" for the city. Meanwhile, officials for the Cinequest film festival publicly accused the mayor's office of pulling $50,000 in previously promised funds because McEnery is chairman of the organization. According to Cinequest executive director Halfdan Hussey, "The mayor's staff told us that 'a big problem here is Tom McEnery.' " Senior mayoral aide Rebecca Dishotsky, who has acted as Gonzales' arts liaison, denies ever warning Cinequest officials that McEnery's involvement threatened the festival's funding from the city. Gonzales says that previous Redevelopment Director Frank Taylor inappropriately promised Cinequest a $50,000 check from his discretionary account, which doesn't require council approval. Hussey says that Cinequest is trying to move past the recent squabble and is now working with the mayor's office to keep the festival in San Jose. Early in his term, the mayor established a competitive grant-application process for nonprofit groups seeking public assistance--the idea being that no one would get any special treatment. Cinequest received $47,000 through that process in 1999, a mayoral spokesman says, plus another $23,000 in technical assistance and downtown festival funds. That's $31,000 less than the festival received the year before under Hammer. THOUGH McENERY REFUSES to air his grievances with the new mayor publicly, he has privately told pals like Mike Fox Sr. that he believes Gonzales has an "enemies list"--and that McEnery is on the list. The mayor's staff brushes off the suggestion of Gonzales having a Nixon-type hit list as laughable. "If there's an enemies list," sneers Jude Barry, the mayor's chief of staff, "it's in some old filing cabinet left over from the McEnery administration." McEnery certainly was not known for his benevolence as mayor. He earned a reputation during his City Hall tenure for banishing nagging council members and out-of-favor home developers. When Councilwoman Nancy Ianni became a thorn in McEnery's paw over the Arena, the mayor backed an attorney pal, Ken Machado, against her in 1988. Ianni, with the help of local Democrats, secured a narrow victory over Machado. Shortly after the election, McEnery demoted then-Councilman Jim Beall--with whom the mayor once nearly came to blows behind the dais--from chairman to vice chair of the transportation and development committee. Gary Schoennauer, the city's planning director throughout McEnery's tenure, recalls that the former mayor considered certain developers persona non grata around City Hall. Among the outcasts, Schoennauer says, was landowner Charles Davidson, who persuaded previous Mayor Janet Gray Hayes--over then Councilman McEnery's objections--to allow him to build single-family homes in a previously untouched part of the protected Almaden Valley urban reserve. "Tom was proud of the fact that he never had an open door to Charlie Davidson," Schoennauer says, "as the previous mayor had." Schoennauer adds that McEnery also didn't care much for Coyote Valley development firm Gibson-Speno, whom the mayor "saw as an enemy of the downtown." Gonzales, too, has developed a reputation during his political career for punishing his enemies. Despite his recent reconciliation with ex-supervisors Rod Diridon Sr. and Zoe Lofgren, Gonzales still has a strained relationship with former county colleague Mike Honda, who didn't endorse Gonzales for supervisor in 1988 or mayor in 1998. Gonzales, a Democrat, hasn't decided whether to back Honda for Congress, even though Honda is the party's nominee against Republican Jim Cunneen. Earlier this year, Gonzales and his chief of staff, Jude Barry, persuaded political ally Nancy Pyle to run against popular District 10 incumbent Pat Dando, Gonzales' opponent in the 1998 mayoral race. Before Pyle announced her candidacy, Dando had actually tried to mend fences with Gonzales, even praising the mayor for his cost-conscious budgeting. Nonetheless, the Gonzales camp didn't want Dando to enjoy a free ride. And she didn't--Dando raised the maximum $90,000 allowed under the voluntary spending cap toward her re-election. Pyle repeatedly criticized Dando during the campaign for, among other things, exaggerating her teaching experience with the tacit approval of Gonzales and Barry. (Pundits say Gonzales himself was worried about going after Dando during the mayoral race because of a potential voter backlash.) Dando cruised to a 49-point victory. The episode is slightly reminiscent of when McEnery threw his weight behind developer Joe Head in the 1988 council election. Head, who eventually prevailed, competed against Dan Minutillo, who had the temerity two years earlier to challenge McEnery's re-election. But Barry insists the mayor doesn't have McEnery on his radar screen. The real problem, Barry says, is McEnery's inability to get along with any San Jose mayor whose last name isn't McEnery. "It's significant that McEnery isn't on speaking terms with his predecessor, Janet Gray Hayes, or his successors, Susan Hammer and Ron Gonzales," Barry argues. There is truth in what Barry says, many San Jose politicos agree. Although Hayes says she maintains a good rapport with McEnery, she acknowledges that she fought with McEnery over the Arena and that he badgered her about her travel budget when he was a councilman. In his 1994 book, The New City-State, McEnery's only reference to Hayes by name refers to her as "the hapless but still-popular Janet Gray Hayes." "I kid him about that," she says. "I tell him not to give me so much ink in his next book." Former aides to McEnery's immediate successor, Susan Hammer, say her relationship with the former mayor became increasingly chilly as well, most evident during her final term. "It went from OK to bad," one aide acknowledges. A pivotal moment between Hammer and McEnery came in 1995, when the two backed opposing candidates in the District 10 City Council election. Hammer supported Meri Maben; McEnery pushed his former aide, Pat Dando. Dando won and teamed up with another McEnery disciple, David Pandori, to become Hammer's most vocal critics on the council. "There was a view in the McEnery camp," says a former Hammer adviser, "that the McEnery era was the golden age--Camelot. The people in his circle were never willing to give up Camelot in their minds--to them, he was king." But unlike the recent flap between Gonzales and McEnery, the Hammer-McEnery feud remained largely covert. The rift was common knowledge among insiders, but it didn't make headlines. Hammer, after all, was a product of the McEnery era and had been close to the mayor when she was the downtown council rep. Instead of cleaning house when she became mayor, she kept on McEnery loyalists like Redevelopment Director Frank Taylor. In November 1997--when sources say their relationship clearly had soured--Hammer still voted to approve a $1.1 million low-interest redevelopment loan to rehabilitate an apartment building owned by a McEnery family partnership. The building, located in San Pedro Square, isn't even in a designated redevelopment area, but the council made a special finding--on Taylor's recommendation--to allow an exception for McEnery. Under Gonzales, such favorable treatment for McEnery hasn't been forthcoming. Camelot is just another withering old building nowadays. THE BEST BULLET POINT on McEnery's résumé in years past was his access to San Jose's most powerful politicians and bureaucrats. But McEnery has no access to the mayor's office now. His allies on the council are few. His council protégé, David Pandori, is out of politics and working as a deputy district attorney. There is still Councilwoman Pat Dando, another ex-McEnery aide, but she operates as a lone wolf (a fate sealed when she lost her bid for mayor against Gonzales). Old McEnery stalwarts in the city administration have also vanished. Longtime Planning Director Gary Schoennauer, who toed the McEnery party line of stopping sprawl and focusing on the downtown, retired in 1997 to work as a development consultant. Most devastating to McEnery's influence was Taylor's retirement last July, when he left amid speculation that Gonzales wanted him gone. (For good measure, Gonzales' handpicked interim redevelopment director, Richard Rios, later axed Deputy Director Jim Forsberg, Taylor's head machete-wielder.) The city's most formidable bureaucrat, a man the local press regularly referred to as "redevelopment czar," he earned the moniker for cutting development deals involving enormous public subsidies without interference from elected officials. And he kept such a tight lid on redevelopment activities that even council members complained about being unable to get information from the agency. "The Redevelopment Agency was a big black box that spit out hotels and other things people liked," recalls political consultant Darren Seaton, a Hammer aide from 1991 to 1994. "It was extremely difficult to find out what was exactly going on over there." McEnery played a significant role in securing Taylor's feudal reign during the next mayoral administration. Before McEnery left office, he engineered a structural change in city government making it so the redevelopment director reported directly to the mayor and City Council instead of the city manager. This allowed Taylor the freedom to cut deals with Mayor Hammer and council members without any interference from the city bureaucracy. One of Gonzales' first priorities as mayor was to reel in Taylor and re-integrate the agency back into the fold. Before Gonzales came along, Taylor enjoyed near-totalitarian control over the agency board's agendas, adding and deleting business items at will right up to the day of the board meeting. Gonzales changed that. The new mayor forced Taylor and the agency to have future agendas reviewed and previewed by the council rules committee--the same process the city manager always had endured. Taylor retired shortly after Gonzales made the change.

Feud Fight: Mayor-once-removed Tom McEnery, after watching Gonzales slash funding for the Cinequest Film Festival where he sat as board chair, says, 'Being in the mayor's office isn't about petty feuds or an enemies list. It involves doing good things for the community.' SAN JOSE SHARKS president Greg Jamison spent nearly six years working with Tom McEnery, the team's vice chairman since 1994 until he resigned without much explanation in February. But even after all that time working together, Jamison can't say exactly what McEnery did for the team. The Sharks are conspicuously not going to fill McEnery's post. Jamison says that the former vice chairman's duties will be spread among senior management. Asked what McEnery actually did day to day, Jamison is vague: McEnery was "involved in a number of different things," Jamison says, and had an "assemblage" of duties. "Can you name a couple of specific duties he performed?" I ask. "No," he says tersely. Ever since McEnery got the Sharks job, wags have joked about his vague role with the team. (The Sharks' press release about his resignation says he "played a leading role in the organization's growing involvement in youth and charitable activities.") Cynics believed that the job was a payoff for his role in building the arena and brokering the Sharks' sweetheart lease; his influence with money-man Taylor was an added benefit. Even though McEnery had just lost his bid for Congress, the fact he could score such a cush gig the same year showed he still had plenty of clout. Likewise, McEnery's resignation was testimony to his diminishing political clout in the Gonzales era. A high-level City Hall source says that McEnery, without all his old connections, had lost his usefulness to the team. Meanwhile, Gonzales has gone out of his way to put his own imprint on San Jose government--one that bears no fingerprints from the McEnery days. He kept council members out of the loop in the selection of a new city manager, redevelopment director and city attorney until the week they were hired. The mayor weeded out the applicant pools and let his colleagues select from his top two choices. The brand-new lineup: City Manager Del Borgsdorf, a recruit from North Carolina; Redevelopment Czarina Susan Shick, Long Beach's longtime redevelopment director; and City Attorney Rick Sawyer, who had worked under his predecessor, Joan Gallo. McENERY, A SAN JOSE NATIVE from a politically connected upper-crust Irish family with a prep-school pedigree, came along at a time when the city needed a shameless booster to champion downtown revitalization. Gonzales, an outsider of working-class stock who emigrated from Sunnyvale, has started the shift away from the more isolationist, downtown-centric policies of his predecessors. The new mayor has shut off the multi-million-dollar redevelopment handouts that were commonplace under McEnery and Hammer. Gonzales threatened to kill a deal to build apartments on the site of the Jose Theatre with Jim Fox if the developer didn't back off his demands to get an extra $400,000 subsidy--a rounding error by old redevelopment standards. And as his single-minded pursuit of a BART link indicates, Gonzales has put regionalism at the forefront of his agenda. (A wise move for a politician presumed to have statewide political aspirations, observes Terry Christensen, a political science professor at San Jose State.) "The focus for San Jose has totally changed," says South Bay political operative Rich Robinson. "McEnery was all about rebuilding the downtown with the Fairmont and the convention center and things like that. Ron is focused on Silicon Valley and making San Jose the real capital of Silicon Valley. His priorities are improving transportation, keeping Cisco [Systems] here and issues outside the downtown." McEnery doesn't sound melancholy about his exile. He's still got a building named after him for his good efforts. And there's even good news on the horizon: The city is expected to locate the statue of McEnery's hero, San Jose pioneer Capt. Thomas Fallon, in Pellier Park this year. The statue, built near the end of McEnery's tenure, has been kept in storage for a decade--what the ex-mayor jokingly called "the witness protection program." Furthermore, McEnery's favored District 6 City Council candidate, Kris Cunningham, is in excellent position to defeat Gonzales' top gun, Ken Yeager, in the general election. But McEnery doesn't sound as if politics are on the brain that much these days. He talks about his film project, his upcoming book on the Bay Area Irish, and an Internet startup he's dabbling in. He insists he doesn't really miss being mayor anymore. "I don't think," he muses, "you should do anything longer than six to eight years." [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the April 13-19, 2000 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 2000 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.