![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

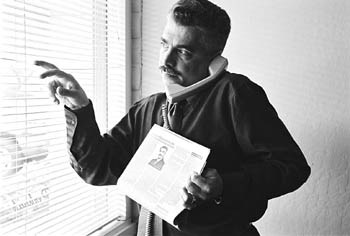

Unsafe Asylum: Local magazine editor Shahbaz Taheri has kept in touch with several Iranian detainees who came to the U.S. for political asylum, and now fear for their lives.

To the Wolves?

Iranian immigrants being detained in prisons post-9/11 say the U.S. government is conducting a secretive and unorthodox program of letting Iranian officials interview them--with the hope of sending them back to Iran, where many fear they will be harmed

By Najeeb Hasan

LATE LAST YEAR, Shahbaz Taheri, editor of the San Jose-based Iranian-American magazine Pezhvak, learned a lesson about the United States government. When the Immigration and Naturalization Services Agency contacted him as part of its homeland security campaign to publicize a new program requiring male immigrants from selected, predominantly Muslim countries to register with the federal government, Taheri was happy to oblige them.

After all, it was in the post-9/11 spirit of halting terrorism, and so he agreed to print--as a public service-- the registration information in his magazine, not knowing that the program would result in the detention and deportation of several hundred Muslim immigrants for minor immigrant-status violations.

In fact, as the national news media relate stories of Pakistani immigrants seeking safe haven in Canada, the ill-fated policy has arguably resulted in perhaps the first post-World War II instance of ethnic groups fleeing the United States in droves to find refuge elsewhere, an ironic reversal of the country's traditional role as the destination for immigrants to avoid intimidation and persecution from unfriendly governments.

The special registrations have predictably resulted in a public outcry from immigration attorneys and advocates, who cite the selective enforcement (only certain Asian, Middle Eastern and African countries are targeted) as patently unfair.

"Many people are going to get deported who have pending petitions [for green cards]," remarks one exasperated immigration attorney. "If that was the case [uniformly], then guess what? Then they have to get rid of half the Mexicans who are here because they have pending petitions and they are waiting for their green cards. Are they really going to do that? I mean, I doubt it ... that will be political suicide."

And so, when Taheri, in good faith, translated the INS information into Farsi and published it in his magazine, the blowback, after the mass detention of Iranians nationwide (Iranians were among the first required to register), caused Taheri to rethink the value of voluntarily cooperating with the federal government. Some readers of Pezhvak, which means "echo" in Farsi, would go as far as to accuse him of being a government agent.

Today, almost three months later, the lesson is being relearned. Indeed, Taheri has helped uncover a quiet round of "consular interviews" of Iranians facing final deportation orders conducted in Arizona and Louisiana in recent months.

While Citizenship officials from the Bureau of Citizenship and Immigration Enforcement (BCIE, formerly part of the now-defunct INS) refused to comment, some Iranian-American attorneys say they have evidence the interviews were conducted by officials representing the Islamic Republic of Iran, a startling turnabout because the United States doesn't have diplomatic relations with Iran (it was named as one of the three countries in President George W. Bush's "axis of evil") and consular interviews are by definition a voluntary process where immigrants are given access to an advocate from their native country, a situation that loses all merit when detainees have fled their native country because of oppression.

Most of those interviewed, immigration attorneys say, don't possess Iranian passports and are likely individuals who came to the United States with the sole aim of fleeing the Iranian government.

In an email circulating in an immigration-attorneys group, one attorney wrote of the consular interviews: "It is akin to the Gestapo interviewing Jews in wartime Europe to facilitate their return to Germany for persecution."

Collect Calling

One of the people rounded up by the government after 9/11 and taken for a "consular interview" was Kouroshe Gholamshahi, a security guard from Sacramento with no criminal record, who was arrested at his home by the INS.

Before that, for the past 17 years, Gholamshahi had been residing in the United States--illegally. An Iranian of Baha'i faith who apparently feared religious persecution in his homeland, he had applied for political asylum in the United States but was rejected (his case was tried by a law student at UC-Davis) and instructed to leave the country voluntarily.

Instead, Gholamshahi opted to duck the law and remain in the United States--a move that was not considered especially risky in the past. He married an American almost five years ago and appeared perhaps on his way toward citizenship (though, because of his deportation order, the matter was complicated) before everything changed after Sept. 11.

Shahbaz Taheri became acquainted with this detainee four months ago, when a jailed and depressed Gholamshahi wrote to his magazine requesting that he send him copies to read. Soon, Gholamshahi began regularly calling Taheri collect from jail. "I'm paying almost $60 every month for the collect calls," says Taheri, who found himself almost involuntarily involved in Gholamshahi's case. As their relationship grew, Taheri alerted private Iranian-American immigration attorneys to what seemed to him as a case of needless detention.

Gholamshahi, Taheri knew, was terrified of being deported to Iran for fear of what would happen to him there. "And each time he calls," Taheri continues, "he wants some kind of assurance through me that something good is going to happen to him, and he keeps asking me, 'Mr. Taheri, what do you think? Do you think I'm going to get out of jail? And what's going to happen to me?'"

Then, about a month ago, Gholamshahi abruptly disappeared from the Sacramento County Jail. His court-appointed federal defender confirmed that the INS, without explanation, had transferred Gholamshahi to its detention facility in Florence, Ariz. When, after a period of silence, Gholamshahi was finally able to make a phone call, he contacted Taheri from Florence and told him that 40 to 50 other Iranians, all on final deportation orders, had been rounded up in the facility and had been interviewed by Iranian officials for the issuance of travel documents back to Iran.

Internet Connected

Needless to say, magazine editor Taheri was amazed. An Iranian dissident himself, who, in Iran, was active in student politics, he had left the country during the time of the Shah and had earned American citizenship and is well aware of the tumultuous relationship between the two nations.

Not believing it was possible that the United States would offer the Iranian government unfettered access to detainees facing deportation back to Iran, he immediately contacted Babak Sotoodeh, president of the Los Angeles-based Alliance of Iranian-Americans. Sotoodeh, upon hearing the news, fired off an email to a lawyers listserve that had been started specifically to deal with INS special registrations.

"I sent an email to our lawyers group," Sotoodeh relates, "saying this is what's going on. It's very strange; has anybody heard a similar thing? And then I got a response that, yes, our people have been removed to Florence too, and they talked to us and said the same thing. So this is how we stumbled upon it."

Meanwhile, 2,000 miles away in Dallas, Texas, immigration attorney Karen Pennington was facing a similar situation. Her client, who requests anonymity for this story because he fears for his life both in the United States and in Iran, was transferred from a county jail in the Midwest to an INS detention facility in Oakdale, La. There, Pennington says, he was only allowed to speak on the telephone with family members twice for two minutes each time.

Pennington learned that her client was being interviewed by officials from Iran for the issuance of travel documents. Horrified, Pennington immediately filed for a Temporary Restraining Order (which was later denied by a federal judge in Dallas), posted a message on an immigration-lawyers listserve and contacted the INS.

The INS, she says, told her they were anticipating chartering a flight out to deport 50 to 75 Iranians. Further, she contends, during the TRO hearing in Dallas, Paul Hunker, the federal prosecutor representing the Bureau of Immigration and Citizenship, informed the judge that her client had been interviewed by Iranian officials.

'Get Rid of These People'

Back in California, Babak Sotoodeh, like Karen Pennington in Dallas, also decided to contact the federal government. He had verified to his satisfaction that interviews by Iranian officials had taken place in Arizona and Louisiana through responses he got from his lawyers groups (for instance, San Diego federal defender Jason Ser also says he had seven Iranian clients transferred to Florence) and through other measures--he had contacted the Florence Project, an immigration-rights organization in Arizona, whose lawyers, after conducting interviews with guards at the Florence detention facility, confirmed for Sotoodeh that the facility was holding Iranian detainees "from all over."

An attorney at the Florence Project says that Sotoodeh did indeed contact them, and the organization reported back that about 50 Iranians facing final deportation orders had been gathered in Florence to undergo consular interviews with Iranian officials.

Concerned, Sotoodeh placed a call to the Iranian desk of the State Department. "The guy right off the bat said, yeah, this is happening," Sotoodeh relates. "I said how can this be happening? He said, well, because INS wants to get rid of these people." Another call to Detention and Enforcement official Lisa Hoechst confirmed to Sotoodeh that the interviews were being conducted by Iranian officials.

The BCIE refused to confirm that the interviews took place.

Forced Interviews

Consular interviews, says an official from the Office of Foreign Missions, are interviews conducted by officers who have the right to visit detention centers in the prisons of the countries they operate in. The catch, though, says the official, is that consular interviews are supposed to be strictly voluntary--if the detainee does not want to speak with the consular official, no coercion is permitted (although the consular official does have the right to verify the noninterest directly from the detainee to ensure the host country itself has not coerced the detainee into the decision).

"That's a consular interview," says a frustrated Sotoodeh. "The counsel comes for my benefit to get me out of jail. Not the counsel shows up to make sure he knows that I've filed for political asylum so that he can write it down and send the information to Iran and make sure that he gets passports to me so I'm deported to Iran and put in jail or die or something. ... These are not consular interviews."

Meanwhile, from the Yuba County Jail in Yuba City, Kouroshe Gholamshahi paints a quite different picture of the consular interview he received than does the official from the Office Foreign Missions. Most importantly, Gholamshahi, who was transferred back to California after the interviews, says a BCIE official had informed the Iranian detainees in Florence that if they didn't meet with the Iranian officials, they would face criminal charges.

Gholamshahi says the Iranian official met with him for about three minutes, asked him questions about his family in Iran and his wife in the United States. Then, after examining his file, the official told him that he didn't know why the BCIE had brought Gholamshahi to him again; he had already rejected Gholamshahi's entrance to Iran three months earlier. Indeed, two other detainees, represented by San Diego federal defender Jason Ser, have already received letters from the Iranian Interest Section saying that the request for travel documents was denied.

"So how come these guys are going through these gymnastics to deport them?" Sotoodeh asks. "The reason is that these guys are political asylum seekers. These are the guys that ran away from Iran without anything. Many of them don't even have a passport. Unfortunately for the U.S. government, if they don't have a passport, they can't deport them to Iran, OK? So, some guy in the State Department or the INS came up with this brilliant idea: Well, how about you contact the Iranian people and make sure they can give them the passport? Now we have a passport; now we can deport them. That's what they're doing."

And in the end, Sotoodeh may very well have the right to be concerned. Although the BCIE isn't breaking any rules, the quiet cooperation between the United States and the Islamic Republic of Iran raises more than a few eyebrows in the Iranian-American community (though some speculate the operation could be an intelligence-gathering attempt by American agents posing as Iranian officials--the BCIE refuses to comment).

Just last May, Amnesty International called for urgent action after publicizing two cases of Iranian asylum seekers deported from Australia. Both cases served lengthy immigration detention in Australia and, when they finally agreed to return to Iran, faced legal charges for criticizing the government. Another man, Amnesty International reports, was forcibly deported and, once in Iran, was executed.

"I'm assuming many people are here because they can't be back in their country," says Faith Nouri, an Iranian-American immigration attorney who also chairs the National Security Entry-Exit Registration System committee of the Los Angeles Bar Association. "We have a very tumultuous history and there is just no question that [Iran] has gone through a lot of changes since revolution, and it is not the same country. Right now in Iran there is no freedom so the government in fact is controlling, is mandating, the behavior for the whole country, for the population. And the people are mandated to behave in a certain way and [those that don't] are going to be basically prosecuted."

[ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

![]()

Photograph by Raymond R. Rodriguez, Jr.

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com.

From the April 17-23, 2003 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.