Blind Justice

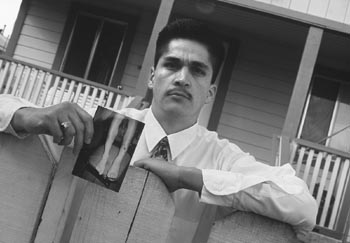

Beaten Man: Norberto Cisneros says San Jose officers shattered his shin when they clubbed him last New Year's Eve. According to police reports, he started the fight.

We will never know the truth about local cops who are accused--rightly or wrongly--of on-the-job violence, even when the city pays public money to the alleged victims

By Cecily Barnes

THE NEW YEAR was still 90 minutes away when six police officers walked up to the Cisneros residence on Pomona Street in San Jose and ordered the "man of the house" to unlatch the front gate. Norberto Cisneros, 30, was throwing a big party, but it was breaking up early and 20 people milled around out front saying goodbye.

When the police yelled for Cisneros, his younger brother Jesus became belligerent. But Norberto walked to open the gate, not wanting any trouble.

"This next part I'm going to tell you all happened in about 30 seconds," Cisneros says, sitting in his living room. "I felt the fence swing open. One of them grabbed me by the shirt and punched me in the rib-cage area. After he did that ..." Cisneros stops telling his story and sticks his fist in his mouth, unable to continue. He looks up at the ceiling, the tears ready to stream down his cheeks. Two minutes pass in silence.

"They were punching me with their fists, all four of them came toward me," he says through glassy eyes. "They were kicking me ... and punching me and clubbing me." Cisneros pauses again.

"Then they picked me up from underneath my arms and dragged me to the car. I said to them, 'I need an ambulance because I'm hurting, and I'm in a lot of pain.' The officer says to me, 'I can't call one because there's too many cars.' About 45 minutes later, they took me to Valley Medical Center."

Zinnia Cisneros sits next to her husband, angrily shaking her head while he talks. "When the cops started hitting him it was like, 'Oh my God, what are you doing?!' " she says. "I'm yelling at them, 'Stop!' and this officer, he was trying to calm me down. While they were hitting Beto [Norberto], he was trying to reason with me. I said, 'OK, I'll be fine if you just stop.' "

But the report San Jose police officers filed that evening tells a very different story.

Officer Peter Perea was first to respond to the dispatch call about a large gang fight at 1457 Pomona Ave. The dispatcher warned Perea that a mob had assembled, clutching rocks and slabs of cement. When he pulled up, some people sped off in cars and others ran from the scene. One man, whose name was not documented, approached Perea, bleeding from the mouth, and told him that the people across the street were "starting shit."

Perea crossed the street to where 40 or 50 people lingered inside and outside the gate. "Based on my training and experience, I associated some of these people to be associated with the local street gang, the West Side Mob," Perea wrote. "Due to the potential violence if the group did not disperse, I began to tell individuals to go home."

When he did this, he says, Jesus Cisneros yelled, "Fuck that, you don't go there!" Perea could smell and see that the man had been drinking and told him to step outside the gate. Cisneros refused, saying, "You come and get me."

"I then entered the yard and attempted to escort Cisneros out to a safer location," Perea wrote. "As Cisneros and I entered the crosswalk to exit the yard, I was jumped from behind and pushed aside."

At that point, he recounts, a fight broke out between the police and several members of the mob. Amid the chaos, Norberto Cisneros came running through the gate and pushed an officer to the ground. Officer Jim Ureta wrote that when he went to assist Perea, "Norberto attacked me, using both of his hands (similar to a football tackle). [He] pushed me to the ground. As I was falling, I grabbed onto him taking him down to the ground with me."

When Cisneros and Ureta were on the ground, Cisneros began "kicking his legs and swinging his arms." Two officers struck Cisneros with batons to protect Ureta.

"Because officer Ureta was down on the ground with the suspect and [Cisneros] was not complying with my commands, I struck the suspect in the legs and arms several times," Officer Michael Obujen wrote.

Ureta handcuffed Cisneros and walked him to his car. However, because he was blocked in by so many police cars, Ureta could not transport Cisneros to the hospital right away. "As soon as the situation was secured," Ureta wrote, "I drove Norberto to VMC."

Accused and Abandoned

FROM THIS POINT ON, the two stories converge. At Valley Medical Center, Cisneros was treated for bruised ribs, a shattered shin bone and head pains. When he was well enough to walk with crutches two days later, he was moved to the Santa Clara County Jail on Hedding Street and charged with two counts of misdemeanor assault on a police officer and resisting arrest.

Almost five months later, it is impossible for the public to know which version of that night's events is more accurate. Even after this case has worked its way through the legal system, there's a good chance the public still won't know. Because of laws intended to guard the privacy of police personnel matters, the public and the media have no access to facts surrounding cases of alleged misconduct. Even after the fact, court documents do not say whether the officers involved were found guilty of wrongdoing or punished.

Of the 45 police misconduct settlements paid out by the city of San Jose since 1994, totaling $720,691, little is known. This is because all police misconduct cases are classified as personnel matters, something the 1976 Peace Officers Bill of Rights has given privacy protection. The SJPD has made liberal use of this right.

New laws pending approval further hinder public scrutiny and prosecution of police misconduct cases.

Forcing the Issue

NORBERTO CISNEROS filed a complaint with San Jose's independent police auditor three days after his release from the hospital on Jan. 5. He is still waiting for a letter to see if the complaint was sustained or if the officers were exonerated. The public will have no access to the findings. Only when a police officer is charged with a crime by the district attorney do victims, the media and the public have access to information about the case.

Last year alone, 102 complaints of unnecessary force were filed with San Jose's independent police auditor, Teresa Guerrero-Daley. But from 1991 to 1996, only nine law enforcement officers countywide were convicted of unlawful use of force on the job, says assistant district attorney Dave Davies.

"They're difficult cases to prosecute in the sense that they always involve issues of reasonable force and self-defense on the part of the officer," Davies says. "Those are areas of the law where only a reasonable doubt needs to be raised to acquit the officer."

But the Human Rights Defense Committee believes that police officers should be held more accountable. Made up mostly of alleged victims of police abuse, the group was formed in 1996 after Gustavo Soto Mesa was shot and killed by a deputy sheriff.

The Human Relations Commission, a similar group appointed by the county, just finished a proposal calling for a civilian review board. The proposal was denied.

"We're very disappointed," says Gertrude Welsh, vice chairperson of the commission.

Most police officers oppose civilian review boards. Guerrero-Daley agrees that they don't work because average citizens aren't qualified to make decisions about police officers. She says public boards can also have the unintended consequence of intimidating a police officer into silence.

"If the officer was going to be honest about what happened, do you think there would be a greater probability that [he or she] would open up to a civilian review board in a public forum, or to a superior in a private forum?" Guerrero-Daley asks. "The officer feels they're being set up for public ridicule."

Tough Job

BECAUSE THEY UNDERSTAND the rapidly evolving situations confronted by officers better than citizens do, police officers are more qualified to make determinations about whether force was necessary, Daley says. As Sgt. Michael Ross puts it, an officer never knows what he or she is walking into. "It evolves so quickly, and you have to make such rapid, quick decisions," Ross says. "It's a tough moment," he says, made tougher if "citizens have the ability to come in hindsight and scrutinize the actions of the officers.

"Do they [the officers] make mistakes? Yeah, they make mistakes," he says. But not many, according to local statistics.

Out of 280,478 calls for service in the 1996-97 fiscal year, only 102 complaints of unnecessary force were filed, Ross says. Of those 102, not one was sustained. Guerrero-Daley, however, isn't sure that no unnecessary force was used.

"The probability that 100 percent of those allegations are false is, to me, just unbelievable," she says. "That a complaint was not sustained doesn't mean it didn't happen. It means it could not be proven. I haven't agreed 100 percent that all of those complaints should not have been sustained."

Lawrence Tyson was responsible for one of these complaints.

In 1991, his complaint reads, four officers beat him with their nightsticks and continued to pound him while he was handcuffed face down on a couch. The officers were in Tyson's home looking for someone else. According to his attorney, Tyson's only crime was standing up to check on his wife.

Tyson's wife, Sharon, filed a complaint with the SJPD's Professional Standards and Conduct Unit. Less than six months later, she got a letter saying the officers had been exonerated.

But in 1992, Judge Gilbert T. Brown dropped the assault charges against Tyson, saying he simply acted to protect himself and his family.

Four years later, Tyson was awarded a $250,000 settlement in a civil suit--the largest amount paid by San Jose in a police misconduct case. To this day, City Attorney Joan Gallo won't concede that the officers used excessive force.

"When we settle a case, it does not mean we think the police officer did anything wrong; that is not a correct standard," Gallo says. "We look and say, 'Are we more likely than not to prevail, and if we were to lose, how much money are we likely to lose?' It's a risk analysis of what will cost the city less money."

Nonetheless, after the city's $250,000 settlement, then Police Chief Lou Cobarruviaz reopened the internal investigation of the officers who, four years earlier, had been exonerated. According to Gallo, the chief stood by the earlier findings exonerating the officers. Although the Tysons heard that the case was being reopened, they were never notified of the new outcome.

"We never found out anything," says Sharon Tyson. "I would have liked to know what the outcome of the findings were. As far as I know, the officers are still employed."

Money for Nothing

IN 1994, A YOUNG MAN high on PCP died as San Jose police officers transported him to Valley Medical Center after he smashed his car into a barbershop. Later his parents sued the city and police department for negligence. The city paid $20,000, and the boy's parents walked away.

"The $20,000 was to avoid what may be a small risk for a large amount of money," Gallo says, explaining that it was cheaper to pay than to risk a jury calling for a $3 million payment.

Taxpayers were never told if the cops had been negligent. While this arrangement makes budgetary sense, it hurts the community's relationship with their police department, Guerrero-Daley says.

"I would prefer that was public information," Guerrero-Daley says. "If people don't hear about these cases, they think they're not happening. Not only that, but having the information public would help the officers that have been falsely accused."

It's the same with the Cisneros case. The police can't comment to defend themselves, since the matter is under investigation, and when it's all over--unless an officer is charged--the files will be sealed.

Sgt. Ross, who works in the Professional Standards and Conduct Unit, says this restriction is a tough break for police officers.

"We have to bite our tongues on what the true facts are, but the complainant can go to you and say anything," Ross says. "It's extremely frustrating because our hands are tied. Like these officers [in the Norberto Cisneros case]--they can't legally answer for themselves in the media, and they're going to watch a news article come out, and they have no say."

This is not the case in many other communities.

In San Francisco, Oakland, San Diego and many other cities, groups of citizens form civilian review boards to investigate cases against police officers. Where such boards are in place, findings are presented at public hearings before the community and media.

The board makes a recommendation to the chief of police as to whether the officer is guilty and if he or she deserves to be disciplined. The finding is then made public.

Whether a city has a citizen review board, an independent police auditor or neither of those is determined by the mayor and City Council.

Until 1993, San Jose had neither. People who had complaints against officers told their stories to other officers working in the department's Professional Standards and Conduct Unit. The unit then investigated the complaints and sent a letter to the complainant about the findings.

In 1991, then-Councilwoman Blanca Alvarado pitched the idea of an independent police complaint office in San Jose, in response to constituents who said filing a complaint at the station itself was intimidating. At a November 1992 meeting, before 400 attendees jammed into the chambers, the council unanimously agreed to hire an independent auditor.

Human rights activists were not satisfied. Having formally requested a civilian review board, the activists began protesting immediately after the council vote. At 12:30am 50 to 75 activists pounded tables and chanted, "Guilty, guilty." Police arrested 24 people to break up the demonstration.

Open Books

TODAY, PEOPLE WHO believe they've been wronged by a police officer can walk into Guerrero-Daley's N. Second Street office and register a verbal complaint. The auditor forwards complaints to the conduct unit for investigation, then attends interviews. But like the police officers, Guerrero-Daley is restricted from speaking publicly about complaints.

That is where an auditor differs from a civilian review board. Sandy Perry from the Human Rights Defense Committee says that public exposure is the key factor in limiting police abuse.

"The principle we're fighting for is community involvement, not just another bureaucratic office," Perry says.

Gertrude Welsh of the Human Relations Commission seconded this principle. "We believe it's not necessarily about bad cops," she says, "but about good government."

But Police Officers Association president Jim Tomaino says citizen review boards rob police officers of privacy. The citizens who sit on these boards, he says, don't understand the responsibilities and dangers of being a police officer.

"How can you take people who don't work a particular position and have them investigating something they don't understand anything about?" Tomaino asks. "Say you have to arrest somebody on PCP. They don't understand what it takes to arrest someone like that. What business is that of non-involved parties?"

According to the ACLU's John Crew, the public are not uninvolved parties. "We're talking about what a public officer is alleged to have done to a member of the public, in public," Crew says. "And if there's a settlement for the officer's alleged misconduct, the taxpayers will have to pay for it."

Art of Darkness

ACCORDING TO Terry Franke, attorney for the First Amendment Coalition, police secrecy around misconduct charges is not new and has been evolving for two decades. The Legislature passed the first police privacy laws, penal codes 832.5 and 832.7, during the 1970s because too many sheriffs' and police departments were reacting to subpoenas by destroying files, Franke says. This epidemic of file destruction followed a Supreme Court decision that prosecutors had the right to information about a police officer's conduct history.

"Rather than combat this lawlessness with prosecution for the crimes of destroying public records, the Legislature was persuaded to enact a new set of rules," Franke says. Under the new guidelines, citizen complaints must be preserved for a period of five years, and are then accessible only through a carefully prescribed species of discovery. The ACLU's Crew believes the Legislature is now continuing this early trend of bowing down to police departments.

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![]()

Christopher Gardner![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

From the April 30-May 6, 1998 issue of Metro.

![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)