![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Viet Offensive

Christopher Gardner The locally owned Vietnamese news media have run up against a corporate giant in the new Viet Mercury. The small publishers fear that they will be driven out of business and the local community will be left with just one paper, which only wants its money. By Will Harper AT 4:30PM ON a Thursday afternoon in April, when most people in the Bank of America building are counting the minutes until quitting time, Tam Nguyen's day is just starting to gain momentum. He has finally finished up with a client in his law office on North First and Taylor streets, and he's ready to start the second half of his day. He gets in his car to drive a mile to the downtown office of Saigon USA, the semiweekly Vietnamese-language newspaper he helped launch two years ago. Saigon USA's nerve center, located in a strip mall on East Santa Clara between Seventh and Eighth streets, is nestled among businesses like Thanh Tam Beauty Center, Khai Thue Income Tax and Kim Huong Restaurant. Tam swings open Saigon USA's front door and walks inside. The greeting area has the cramped feel and size of a doctor's waiting room: To the left is a dusty off-white couch set (a hand-me-down from one of Tam's friends) and a wood-and-glass coffee table; to the right, a white desk with an old 486 computer on top. In the back, the entrance to the newspaper's advertising "division"--in reality a 6-foot-by-8-foot room with a computer, printer, desk and file rack--still has a drawstring curtain from the days when it was an examination room for a chiropractor's office. But there are clear indications we are in the right place. Take the 15 Saigon USA covers neatly tacked up on the walls, bearing headlines and stories from the past year about the California gubernatorial race, U.S. Senate candidate Matt Fong, and a debate between San Jose mayoral candidates Pat Dando and Ron Gonzales. The masthead design for Saigon USA and the splashy color cover page is reminiscent of USA Today. But in spite of the splashy design, this is still an amateur operation. The paper has no full-time employees. The people pecking away on keyboards and clicking the mice in the old examination rooms are either volunteers or part-time workers. One woman is a business student at San Jose State University. The photographer doubles as the newspaper's bill collector. The publisher, Minh Do, used to work as a pharmacist in Vietnam. Editor-in-chief Khiem Hanh, a cherubic middle-aged man with dark circles under his eyes, had a paper in Saigon that specialized in uncovering government corruption. Now, in addition to this job, he makes his living from a janitorial service. Tam was a first-year journalism student when Saigon fell to the Communists in 1975. Shortly thereafter, at the age of 18, Tam came to the United States. And that pretty much sums up the news background of Saigon USA's managing editor. (The staff box lists the managing editor as Le Phong. That's Tam's pen name, which is also the name of a popular mystery-solver in Vietnamese fiction.) Since coming to the States, Tam has earned a degree in music, spent several years as an engineer and owned a photography shop. He became a lawyer in 1991. His law practice pays the bills, he says, but Saigon USA is his passion. "This is more like a social statement," Tam says of his shoestring operation. "It's more of a community activity than a business. Our goal is to break even." Most advertisers, according to Tam, are friends or acquaintances. So are many contributors, who email stories, snippets and tips from all over the state. The previous night, Hanh was up until 3am wading through and editing dozens of email submissions. (He had to drive his daughter to school five hours later.) As the night progresses, Tam kicks off his tasseled brown loafers, loosens his tie and unbuttons the top of his button-down white shirt. By 10pm, he and Hanh have already scrapped two cover stories and are moving on to a third idea. They ultimately decide to go with a story on San Jose Bishop Pierre Dumaine, who, after a 13-year struggle, has agreed to give Vietnamese Catholics their own parish. In a move that would make many American newspapers cringe, the Saigon USA front-page story on the subject is being written by Bai An Tran, the person who led the fight to get the parish. Tran also supplied the photograph for the story. But passion in this tiny publishing enclave is everything, and this story is no exception. After putting the finishing touches on the paper, Tam boxes it up to go to Pizazz Printing off Oakland Road. It is 2am. Tam has to be in court in Gilroy in just six hours, at 8am. THREE MILES UP THE ROAD, off of Interstate 880, another Vietnamese language newspaper is preparing to go to press. It will be delivered to more than 500 locations throughout the valley next to Vietnamese grocery stores, inside restaurants and on street corners. It operates out of the headquarters of its English-speaking sister newspaper--which generated nearly $280 million in revenues last year--in a building with more than 1 million usable square feet located on 52 acres on a street with the same name as the company's chairman and CEO. The property at 750 Ridder Park Drive and an adjacent parcel--including land, buildings and equipment--are valued at nearly $70 million by the county assessor. The parent corporation is the second-largest newspaper chain in the country, with 52 daily and nondaily newspapers in 28 U.S markets that grossed $3.1 billion in 1998. The publicly traded company has been pushing its new free Vietnamese weekly since its premier issue three months ago, and it has flourished. Prior to the paper's launch, its editor told a trade magazine that the company planned to start out with a 32-page tabloid. By April, the paper had grown to 128 pages, thanks to increased advertising. Publishers of competing Vietnamese publications--many of them mom-and-pop operations without a full-time staff--feel that accounts have been snatched away. Some have even accused the Viet Mercury of trying to run them out of business. When asked about the new paper's business practices, the publisher declared that his paper "isn't about competing with other Vietnamese publishers, it's about offering a mix of products and representing the community."

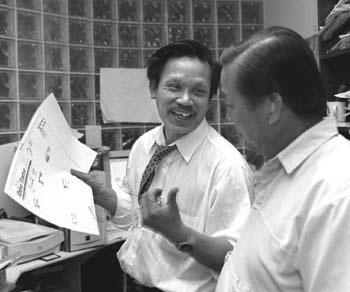

Print of Peace: 'This is more like a social statement,' says Saigon USA co-founder Tam Nguyen. 'It's more of a community activity than a business.' THE PROJECT HAD BEEN a long time in the making. On Feb. 2 at the San Jose Athletic Club, San Jose Mercury News publisher Jay T. Harris hosted a party celebrating the new venture: the Viet Mercury, a Vietnamese-language weekly. Times were changing, Harris told an audience that included Mayor Ron Gonzales, and the Mercury planned to change with them. There are approximately 120,000 Vietnamese living in the valley and about 5,000 Vietnamese businesses. Among those celebrating the christening of Viet Mercury was Val Hoang, an entrepreneur who runs and owns the Internet Metropolitan Vietnamese Network, a sort of virtual Vietnamese yellow pages. IMVN, which Hoang says has fewer than 10 employees, also manages the websites for newspapers like the San Jose-based daily Thoi Bao (Vietnam Times). Hoang says he felt proud to have the prestigious Mercury News printing a newspaper in Vietnamese--it was an acknowledgment of the community's buying power. He left that night with a complimentary Viet Mercury coffee cup. And then, he says with more than a hint of bitterness, some strange things started happening. HOANG SAYS HE FIRST came in contact with representatives from the Mercury News--including Lan Calderon, now project development manager for the Viet Mercury--about 18 months ago. He says they contacted him, suggesting a joint business venture on the Internet. As Hoang recalls their pitch, the Merc people liked that IMVN had established Vietnamese business contacts. "They were looking for a short cut," he says. Hoang says he put together a business proposal, at their request. Weeks went by without a word. Then Hoang says he was asked to put together another business proposal. Nothing came of that either. In the process, though, one of his sales employees went to work at the new Viet Mercury. Another former IMVN salesperson also started punching a timecard at 750 Ridder Park Drive. At first, Hoang says, he didn't think about the situation much. In fact, he insists he was happy for his old staffers; they were now working for a big company that could pay them more. And he still thought of the Mercury as his friend. The Viet Mercury even ran a feature story on Hoang's business in its second issue. Then, Hoang says, an odd thing happened that changed his mind about his "friend." One day, someone called his office asking to speak to "Willie Smith." No one with that name works at IMVN. Hoang decided to Star-69 the caller to trace the origin of the call. Hoang claims the person on the other end turned out to be a sales manager at the Viet Mercury who was looking for new people. Hoang--who concedes he has no direct proof of tampering--says it doesn't bother him if his employees are being recruited. It's the surreptitious way he thinks they have been recruited which bothers him, especially after Mercury reps had initially approached Hoang as a potential business partner and ally. "I have concluded that they are not my friends," Hoang says. "I don't trust them." Hoang's complaints sounded familiar to some local Vietnamese publishers. When he started asking around, he learned that an editorial staffer from Thoi Bao had also gone to work at Viet Mercury, as well as an ad designer who worked for several of the local Vietnamese papers. (Mercury News controller Ray MacLean, who didn't return phone calls from Metro, told the Business Journal that the people they hired came in response to job ads.) But the Vietnamese press barons weren't as concerned about employee attrition. They were beginning to lose something even more important. TAM NGUYEN OF Saigon USA recalls that shortly after the Viet Mercury's debut issue his paper began losing advertisers. "Our clients would say, 'I'm sorry, there was this offer I couldn't refuse. It's too good.' " The too-good-to-refuse offer, according to Tam and other local Vietnamese publishers, was from the Viet Mercury. Gia Dinh, a San Jose newspaper, ran an article accusing the Viet Mercury of low-balling advertising rates in order to win over new clients from its competitors. Gia Dinh estimated the Mercury's printing and operating costs at about $300 a page. A contract obtained by one of the rival publishers shows the Viet Mercury charging an introductory rate of $45 an ad for half-page horizontal ads running in the paper's first 13 issues; for the remainder of the year, the ad rate in the contract goes up to $75. Vinh Phan, co-publisher of the semimonthly family magazine Me Viet Nam (Vietnam Mom), says his publication has lost 10 full-page accounts since the Viet Mercury hit the streets. "Advertisers who have been with us for years are suddenly saying goodbye to us," Phan grouses, "[saying that] their budget doesn't permit it anymore." What makes small-time publishers like Phan nervous is that they don't have the resources to compete with a $3 billion corporate giant like Knight Ridder, which can afford to let the Viet Mercury lose money while it accumulates market share. "Our concern," Phan explains, "is that one day there's going to be only one voice"--the voice of the American-owned Viet Mercury.

Christopher Gardner

THE NEWSPAPER WAR has evoked an intense response from Vietnamese publishers who remember the perils of having only one political voice--that of the Communists who took over their homeland. Over the past two months, cover stories and editorials about the evil Viet Mercury have abounded in the Vietnamese papers. Viet Nam Tu-Do has accused the Mercury of "illegal competition." In an editorial called "American Paper, American Owner," the bilingual San Jose semiweekly Calitoday refers to a "plague" of American-owned Vietnamese papers (even though, according to the Business Journal, the Viet Mercury is the first Vietnamese newspaper launched in the U.S. by the publisher of an English-language daily newspaper). In interviews, Tam of Saigon USA--which ran two front-page editorials on the Viet Mercury in one week alone in April--invokes emotionally laden words like "betrayal." What infuriates Tam Nguyen most is the way Mercury publisher Jay Harris sanitizes what is ultimately a business decision to reach a new market by claiming it is a lofty and noble effort to "represent" the community. Tam asks rhetorically: How are they serving the community by trying to put Vietnamese-owned papers out of business? "If this is a business decision, then say so," he demands. "Don't hide behind the facade of 'serving' the community." The newspapers that have served the South Bay Vietnamese-American community over the past decade--there are currently three dailies, and about a dozen weeklies and semiweeklies--have largely reflected the fervent anti-communism of Vietnamese immigrants. This is a culture, after all, that protested en masse when a store owner had the temerity to hang a poster of Viet Cong leader Ho Chi Minh. It is the same culture that produced a hunger strike earlier this year in front of a government-supported refugee center in San Jose because people felt the director was sympathetic to Communists. In November 1990, the former publisher of San Jose's Vietnam Daily News lit himself on fire in front of the U.S. Capitol apparently to protest Communist rule in Vietnam. "The Vietnamese community is not like other ethnic communities," explains Chau Nguyen, the editor of the general interest magazine Thi Truoung Tu Do (Free Market), which recently ran a cover story on the Viet Mercury. "We are political refugees. We were persecuted by the Communists." CHAU NGUYEN, a Michael J. Fox-size 60-year-old philosophy professor with wispy gray hair, was himself a political prisoner in Vietnam for seven years. He came to the United States nine years ago. Of the Viet Mercury and its American owners Chau opines, "I don't think they understand the pain of the Vietnamese community." But while competing publishers and editors gripe about the Viet Mercury, not everyone is complaining, least of all the Vietnamese Chamber of Commerce, which has benefited from the Viet Mercury's sponsorships of the Tet Festival and the annual awards dinner. "The reaction has been mixed," acknowledges Thuan Nguyen, executive director of the Vietnamese Chamber, quickly adding that the Viet Mercury brings a higher standard of objective news coverage to readers. "Most of the Vietnamese papers, because of limited resources, either just translate the news they buy or just sum up the story," he adds. "The Viet Mercury is going to be able to cover a wider range of topics in different areas of the community." Viet Mercury editor De Tran, a veteran reporter for the Mercury News and the Los Angeles Times, contrasted his paper with the other Vietnamese papers less diplomatically in an interview with Editor & Publisher magazine in November: "They don't have reporters. They don't have a staff. A lot of times they steal stuff." THE MISTRUST in the newspaper war has not been one-sided. In March, Mercury officials began to suspect that the reason Viet Mercury racks were emptying so quickly was not just the paper's popularity. They had information suggesting the papers were being stolen. The San Jose police were notified of the possible thefts. Then publisher Jay Harris wrote other Vietnamese publishers in the area to alert them. "We are not certain that this theft is targeted at our Viet Mercury or any other Vietnamese publication in San Jose," Harris wrote in a March 17 letter labeled "confidential." "Nevertheless, we wanted to be sure you are aware of this threat. I am sure you will agree with me that any such act, regardless of its motivation, would be inconsistent with this nation's tradition of press freedom. "I am equally sure," Harris continued, "that you will agree with me that any attempt to thwart press freedom must be vigorously resisted. We are committed to doing so." If relations between the Mercury and its competitors were already heated, Harris' letter brought them to a boil. Vietnamese publishers took the letter as a veiled accusation that they were behind the theft. "It was an insult," Tam Nguyen says. In response, Thoi Bao published a sarcastic open letter to Harris (translated by New Community Media on its web page): "We don't know the details as to how your papers were stolen. Did the miscreants take your boxes away? Did they throw them in the garbage? "These details are very important. From our experience, many older readers of Thoi Bao take many copies each time so they can distribute them to their neighbors and relatives. We worry that these readers may not know your concerns and ... the police ... would handcuff them and accuse them of stealing and opposing the freedom of the media." The missive concludes by underscoring the David and Goliath battle between the Mercury and the local Vietnamese press: "But what we experience may not be what you will experience. If we can use the Vietnam War as a metaphor, then our paper is like the village guard by the river, relying on the villagers to give him rice to keep the fort protected while he fishes and grows vegetables to keep going. "Whereas Mr. Harris's paper is like a soldier from the Number One battalion who takes showers from water delivered by helicopters, who has strong firepower, and who, with a single encounter with a sniper, calls in for B-52 bombs. "Our freedom of the press is like the life of the village guard on his little fort. And your freedom of the press is like that warrior in the tank, parked behind the battle zone. We live under the same sky but we do not share the same experience." THE Viet Mercury is the Mercury News' second publishing foray into local ethnic communities. The first, a Spanish-language weekly called Nuevo Mundo, debuted in May 1996. The principle behind the creation of Nuevo Mundo was much the same as that of the Viet Mercury: In order to reach the valley's 400,000 Latinos, Mercury News managers felt they couldn't do it in English--they would need to reach out to Hispanics in their native tongue. "I would say they are areas for very great potential growth," Mercury News publisher Harris told Editor & Publisher magazine in March. "These are communities that are large and are growing rapidly." (Harris and other Mercury officials didn't return repeated phone calls.) There are obvious parallels between the controversies sparked by the introduction of Nuevo Mundo and Viet Mercury. For instance, the publishers of already established Spanish-language San Jose papers La Oferta Review, El Observador and Alianza Metropolitan News complained that Nuevo Mundo was stealing their advertisers. They also believed they would be driven out of business, but this has not occurred. Emil Guillermo, a columnist for Asian Week, argues there is a reason for the recurring theme in the Mercury's ventures into ethnic communities. According to Guillermo, corporate news media have taken two approaches to addressing the country's burgeoning ethnic populations: one is cooperative; one is competitive. For the cooperative approach, Guillermo points to the method used by the Los Angeles Times. In recent years, the Times has partnered with an existing regional Vietnamese paper and a Spanish one, La Opinion. The Mercury News and Knight Ridder, Guillermo says, have taken the winner-take-all competitive approach with Nuevo Mundo and the Viet Mercury. That is why the introduction of those papers has caused so much acrimony. In a column titled "When Mainstream Goes Ethnic," Guillermo writes, "Two models. Two ways of tapping into emerging markets. One way is more zero-sum than the other. ... Standard mainstream corporate-think. ... The other is slightly more community-friendly. Partners, not competitors." It's not as if the Mercury News didn't have a chance to become a partner. The owners of the now-defunct Viet Magazine spent several months trying to arrange a joint venture without success. Nam Nguyen, former editor of Viet Magazine and now the editor of the bilingual Calitoday, says he doesn't think there is much use in complaining about the Viet Mercury at this point. The war has already started. The object now is to prevail or at least survive. To do so, Nam argues, local publishers will need to persuade readers that they have a better product. Despite Viet Mercury's vast corporate resources, Nam thinks papers like his can make it. "The Vietnamese paper owned by the Vietnamese people," he says, "can cover the Vietnamese community better." [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the May 6-12, 1999 issue of Metro.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

Small Pressman: Managing editor Tam Nguyen outside the 'headquarters' of Saigon USA, which used to be a chiropractor's office. Three miles away, the Viet Mercury is produced in a building with more than 1 million usable square feet on property valued near $70 million.

Small Pressman: Managing editor Tam Nguyen outside the 'headquarters' of Saigon USA, which used to be a chiropractor's office. Three miles away, the Viet Mercury is produced in a building with more than 1 million usable square feet on property valued near $70 million.