![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Just Say Neighbor

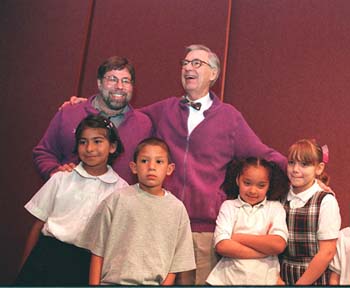

Chris Gardner Mr. Rogers wins Children's Discovery Museum award and brings a beautiful day to San Jose By Corinne Asturias NOT EVERYONE CAN get a room full of reporters, photographers, museum administrators and Steve Wozniak to sing "It's a Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood." Even if it is a beautiful day. Then again, not everyone can appear to make eye contact with and mesmerize close to 1,000 people they don't know. Not everyone is Mr. (Fred) Rogers, who has calmed and inspired children for more than 30 years and was recently brought to San Jose to receive the Legacy for Children award from the Children's Discovery Museum. "You can't rush him. He does things in his own way, in his own time," the CDM's Karen McBride had explained to an impatient media horde earlier. "And he's very sincere," she added, as one rushed journalist rolled his eyes. Mr. Rogers doesn't roll his eyes. He doesn't clear his throat. He doesn't forget what he's saying in the middle of his sentence. He doesn't let his voice trail off. He doesn't prattle and he pronounces everything very slowly and very carefully, to make sure no one gets confused. It's quite a relief, really. Mr. Rogers stands there, looking pleased. The CDM people have given him a brilliant purple sweater with a zipper, to add to his collection. At 70 years old, his hair is more salt than pepper. Beneath his whitened eyebrows, his eyes seem to twinkle. His teeth have become a little craggy, making his smile seem more real. "The greatest gift you can give someone is your honest self," he says. Mr. Rogers doesn't overexplain. What he does is release nuggets of positive thought, one at a time, with lots of air in between. "Human beings," he says, standing in front of a room full of panty-hosed, besuited, beeper-wearing and cell-phone-laden $150-a-head eggs-benedict-eating listeners at the Fairmont Hotel, "are very deep and very simple." He mentions how the tensions of our world pull us into an unnatural state. "How we end up knowing more about people who live in Littleton, Colo., than we do about our own neighbors." He shares favorite quotes and film clips from his show, pronouncing at the end: "The greatest hope in the world lies in the heart of those who are able to care for others." Then he brings the audience to tears by saying nothing at all. He asks everyone to share a moment of silence to remember one person who helped them as a child to live their life "in a way that was good and real." The 750 people in the room do this and some cry. When we meet in the emptied-out CDM theater, the lights are low. I have read Esquire's cover story from November, where Mr. Rogers is described as a hero. But I am not nervous. I tell him how my teenage sons used to watch his show when they were young, but now things are more complicated. "A friend of mine who is a psychologist," he says, enunciating each word as if it might be his last, "once told me that the changes a teenager goes through is the closest to psychosis a person can get without being ill." We sit there in silence, breathing in this thought. I ask him about his own two sons and the episode of Mister Rogers' Neighborhood when they were featured guests. I don't repeat these details, but one of them, I remember, picked his nose until Mr. Rogers was forced to give him The Look. The other one kept on feeding the fish until Mr. Rogers had to tell him, in a somewhat firm voice, to stop. Twice. He looks off through his horn-rimmed glasses to locate this memory in time, then smiles broadly. I ask him if it was intentional, for them to misbehave a bit. Or was it just--an accident? "No, it wasn't planned that way," he says. "But there would have been a chance to tape the show over again, and we opted not to." He tells me that he often chooses to leave mishaps in the program. "I want children to see that things don't always work out, even for adults," he explains. There is too much attempt at perfection on television, he says. "It makes it so you think that anything less than 110 is failure." As we say goodbye, he takes my hand and clasps it warmly. He looks into my eyes and tells me it's been so nice to visit. As I leave, I feel he is one of the most genuine people I have ever met. Then something hits me: to him, in his utter calmness, I must have seemed like a nattering fool. Why didn't I ask him about public education, or what he thinks is wrong with television today? Did I even make eye contact? No! I was probably too busy scribbling in my notebook. But before I get carried away, I realize what Mr. Rogers would say. He would say he likes me just the way I am. [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the May 6-12, 1999 issue of Metro.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.