![[Metroactive Arts]](/arts/gifs/art468.gif)

[ Arts Index | Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

Lomographs by Brian Eder, Yina Kim, Lisa Knowles, Cherri Lakey The View from Here How one Russian camera took over the world, and set up a not-so-secret base right in San Jose By Traci Vogel TWO FISH DESIGN studio doesn't exactly look like the setting for a socialist revolution. Carved from an old brick-walled iron foundry, the studio features a warren of side offices, scuffed wood flooring, and a gallery space littered, on the day I visited, with old office furniture, folding chairs and stacks of large pieces of plywood mounted with careful mosaiclike arrangements of photographs. The photographs seemed to be grouped by color. In some groupings, a child's face, blurred by its proximity to the camera lens, complements the pale fade of a sunset, which ends up next to a fence painted sky blue, arcing away in perspective. On top of one stack sits the photo of a sculpture of a man dancing, blown up to about 3 feet by 2 feet. The statue appears to be situated in one corner of a garden, next to a vine-covered wall. The image, slightly blurred, gives the impression of movement or hurried photography. It's an arresting scene, and Cherri Lakey, Two Fish's co-owner, and I stop to gaze at it. "Everyone keeps asking me where that statue is," Cherri says, touching one corner of the photo. "We haven't been able to figure it out yet. It's somewhere in San Jose, but it doesn't look like San Jose." A few days later, while leafing through a how-to booklet for the Lomo camera, I see Rules No. 8 and 9: "8. You don't have to know beforehand what you captured on film. 9. ...Afterwards either." Where is this image? Of what time period? Who is this a picture of? These are all questions the Lomo owner learns to stop worrying about. Context is not the concern of the Lomo photographer. Beauty is.

"What the hell is Lomo?" The question plasters Lomo's promotional material, the website (www.lomography.com) and the how-to manual that accompanies your Lomo purchase. According to these materials, Lomo's quirky history begins late in Soviet-era Russia, in 1982. Spurred to competition by mass-manufactured Japanese minicameras, the Russian minister of defense and industry collaborates with the Lomo Russian Arms and Optical Factory to furnish their comrades with a cheap, but high-quality, people's camera to document their frolicking class-free lives. In order to keep manufacturing costs low, the body of the Lomo Kompakt Automat camera (LC-A) gets made with plenty of plastic.

Fast-forward to the summer of 1991, to a group of Viennese students vacationing in newly democratic Czechoslovakia. Wandering the shops in Prague, the students purchase a couple of old cameras and start shooting reams of film at random. Back in Vienna, they're astonished to discover that the photographs develop into circus-colored shots with an immediacy that recalls the essence of their heady summer. At this point, the Lomo factory in St. Petersburg is out of business, so early fans of the Lomo camera begin to scour shops in the disintegrating Soviet empire, so they can sneak them out. In 1992, interest in the cameras grows to the point where two Viennese friends, musing over rounds of vodka, decide to establish a Lomographic Society in Vienna. Subsequently, Lomo Embassies open in cities around the world. The burgeoning fan club then convinces none other than Russian Premier Vladimir Putin (at the time, the vice mayor of St. Petersburg) to reinstitute Lomo production. He does, and the Lomo is reborn.

Enter Cherri Lakey and Brian Eder of Two Fish Design in San Jose. Cherri, who had purchased a Lomo for Brian for his birthday after seeing a tiny ad in some magazine she doesn't remember, contacted the organization's founders. Two years and a few ambassadorial trips later, San Jose became one of four Lomo Embassy sites in the United States--the others are Washington, D.C., New York and Los Angeles. Being an embassy allows for the throwing of events, such as the recent "Lomo on Ice," in which Lomographers met at San Jose's ice rink dressed in bright colors, and took shots while on wobbly ice skate blades. Embassy status also makes San Jose a flash point for world-traveling Lomographers (and they do seem to do a lot of traveling, judging from the online photo galleries, or "Lomohomes"), and lets Cherri offer programs such as the Lend-a-Lomo, in which interested parties may borrow a camera for two hours during organized events. Two Fish Design is also an official Lomo sales outlet, so if you're hyped on the Lomo after trying it, you can drop $170 for a camera of your own. Or you can buy one from the Lomo website for $10 more.

Cherri likes the way the Lomographic outlook draws different cultures and personalities together. "We loved the fact that there were Lomohomes on the web. People from all over the world communicate through these photos. It's a weird little thing, but it's amazing how it brings people together," she says. This may all sound like so much hype--after all, this is just a 35 mm camera, right?--but Cherri insists she's seen firsthand evidence of this phenomenon in the Lomo Wall events Two Fish Design has organized with the help of the San Jose Redevelopment Agency. In the most recent display, children aged 4 to 15 were paired up with adult Silicon Valley movers and shakers, and their disparate views of local life can now be seen hanging on Lomo Walls at 76 S. First Street, on exhibit until June 1. (Conflict of interest caveat: Metro is a sponsor of this exhibit.)

→ 1. Take your Lomo everywhere you go. → 2. Use it anytime--day and night. → 3. Lomography is not an interference in your life, but a part of it. → 4. Shoot from the hip. → 5. Approach the objects of your Lomographic desire as close as possible. → 6. Don't think. → 7. Be fast. → 8. You don't have to know beforehand what you captured on film. → 9. Afterwards either. → 10. Don't worry about the rules. This is a revolution, but not one that takes itself too seriously. Furthermore, it's a revolution that uses the Internet to spread its aesthetic impulses, as Lomo Society members scan photos to share with others around the world, but it's a movement that scorns high-tech goodies like Photoshop and digital photography. Lomo is full of cognitive dissonance.

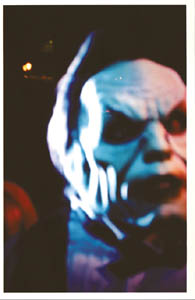

In the spirit of not taking things too seriously, Lomohead Yina Kim prefers to focus on Rule No. 10. "I don't really care about the rules," the middle schooler insists. Then she pauses philosophically. "I like rule No. 10. Does that mean I care about the rules since I care about rule No. 10?" "Sometimes I cheat," Yina continues. "I always wonder what's in my film, what I've captured." Yina's photographs seem remarkably sophisticated for a 16-year-old. Her Lomohome (yinny.net/photo.htm) displays images whose character depends on light effects, strange angles and kitschy subject matter. Yina does profess an interest in the art, praising the Lomo's "warm-feeling pictures." She's also fascinated by the technical aspects. "I'm very interested in old cameras," she says. "Recently, I got an Agat 18K, which takes half-frame pictures. I love to take pictures. It captures my life, my memories. The bad thing about taking pictures is I'm too busy and poor these days, I can't afford film and developing.'

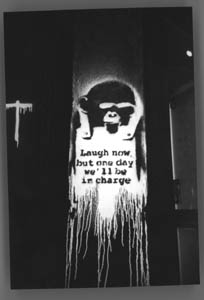

Lisa Knowles, a San Francisco-based graphic designer, echoes Yina's sentiments, albeit slightly more soberly. When asked how she got into Lomography, Lisa says, "I think I maybe took a black-and-white photography class in high school. I have a nice 35 mm camera. But every shot I got back was exactly as I saw it, remembered it. Boring." In contrast, the shots from her Lomo arrived with unexpected details and moods. "The Lomo philosophy appeals to me because it offers a way to be visually creative without being overly critical of the outcome. Any composition you can visualize can be improved by allowing a bit of the unknown to enter in." Lisa was introduced to the Lomo by a friend who owned an early Holga (the Holga is another Russian-made camera carried by Lomo, but it takes 120, or medium-format, film, as opposed to the Lomo's 35 mm). Through the Holga, she was initiated into the Lomo cult: "We entered the international sampling album contest, and as runners-up both won LC-As. This new freedom--'don't think, just shoot'--allows me to ignore the rules of good composition and get fresh results, better compositions, better colors, better shapes. To ultimately see from new angles." "Plus," Lisa continues, "I got into the whole science experiment portion. I've bought old Brownies and borrowed cameras from friends--made color transfers from scans of photos and applied them to other photos." "I carry my LC-A everywhere, pushing the limits--hand-holding flashes, getting up at 5am to take long exposures in the early morning light. Drinking pints and capturing the night. People always want to know what I'm up to. Who is this crazy girl who doesn't look where she's shooting?"

Listening to all these breathless testimonials about the life-changing nature of Lomography left me a little unnerved, so when Cherri offered to lend me a Lomo, I agreed with open skepticism, even antagonism. "I think I might be the worst photographer in the world," I said, taking the innocuous-looking boxy camera in hand. This is hardly an exaggeration--my photographs usually look nothing like their supposed subject matter. When I think I'm too close to something, it turns up occupying one tiny corner and looking like it's a mile away. My friends look so unlike themselves in my pictures that even they end up pointing at the photos on my wall and asking, "Hey, who is that?" Cherri, good cult leader that she is, simply smiled encouragingly and said, "Don't worry." Over the next three days, I took my Lomo everywhere I went--about 50 percent of the time. On the occasions I forgot it; I found myself looking at things I might not have noticed and thinking, "Damn, I wish I'd brought the Lomo."

Reading, "You are addicted to people, colors, glances, stories, long noses and chubby cheeks. ... You want in, to get closer to people and things and at their real lives, to home in on their very essence," I thought, "Yes! That's me! How did they know?" An appreciation for imperfection is part and parcel of the Lomo creed. In my hand, the Lomo itself sits like a tank, with unwieldy corners and oddly placed buttons. Unlike modern ergonomic gadgets, the Lomo does not, at first, feel natural. Anyone impatient with inefficiency would hate it. To the growing number of aesthetes who despise technology's slick production values and disparage the inexorable search for perfection, however, Lomo is a godsend. In her seminal book, On Photography, Susan Sontag writes about how photographs, rather than capturing objective reality, actually help us edit the world around us. Sontag says, "To photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed. It means putting oneself into a certain relation to the world that feels like knowledge--and, therefore, like power."

And yet, this is not a camera of the digital age. Rather than having the ability to discard images immediately if they don't fit the photographer's ideal like digital camera buffs are able to, the Lomohead gets back a packet of random information when she picks her film up from the developer. And it is this very randomness that gives the Lomograph its desired imperfection, its post-moment beauty.

Such imperfection also allows artists to experiment with adapting their instrument. "You can rip the spring out and do bulb settings," Knowles explains. "Duct-taping them to free-standing objects, trees, stop signs, et cetera. Take 30-minute exposures, et cetera." "When you don't look through the viewfinder, every shot is a surprise. ... It's great; I pick up a roll from Photoworks, and it is always a surprise; some rolls are amazing, others miss the mark completely."

Keeping this in mind, I tried not to be too critical when I picked my Lomo photos up from the developer. Out of 24 photos, 22 looked like blurry snapshots. Only two turned out to have any Lomo ambience, but those two made me stop, stare and rethink the photos' subjects. In both, the subjects looked as if they'd been, not idealized, but moved to some metaphorical level I hadn't been aware of. Looking at them felt like looking at a movie made of my life. This, I thought, could get addictive.

San Jose Lomographic Embassy; 150 So. Montgomery Street Unit B; San Jose, CA 95110; Tel. 408.271.5151, Fax 408.271.5152; www.galleryAD.com/lomo Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com. [ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

|

From the May 8-14, 2003 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.