![[Metroactive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

The Gay Golem

Gary Indiana delves into Andrew Cunanan's psyche; Maureen Orth reviles the homicidal homosexual

By Michelle Goldberg

YOU HAVE TO LOVE your villains. It's a piece of oft-quoted advice, mostly from one writer to another, and mostly when the subject is fiction, but it may be equally true in the amorphous field of highbrow true crime. That adage goes a long way toward explaining why Gary Indiana's Three-Month Fever: The Andrew Cunanan Story is such a riveting, alarmingly insightful book, and why Maureen Orth's Vulgar Favors: Andrew Cunanan, Gianni Versace and the Largest Failed Manhunt in U.S. History is such a dismal and intermittently offensive bore.

Indiana grew to like Cunanan, or at least empathize with him--the most disturbing thing about his portrait of the infamous spree killer is how familiar Andrew Cunanan seems, how nearly indistinguishable his rage for fame was from that of any smart kid who hates himself and understands what our culture loves. Orth, conversely, sees Cunanan as a queer monster, a trashy pervert whose crimes were almost inevitable given his twisted predilections.

The epigraphs alone set the books' opposing tones. Orth quotes Richard Strauss: "Just look at the vulgar favors that give the crowds of the capital such delight. ... You despise these lewd doings and yet you suffer them." To her, Cunanan's world was a homosexual version of a Hieronymus Bosch painting that fascinates as it appalls.

But this world is Indiana's world, and one of his opening quotes, from a poem by Dory Previn, preempts easy condescension.

Last night I found obscenities

"I wasn't expecting it going into it," Indiana says in an interview conducted over drinks, "but by the time I got through I felt that this might not be somebody I'd want to have as a best friend or anything like that, but he was somebody who could have gone another way and been a really interesting person." A fey, bitchily charming, cunningly intellectual writer, Indiana says the more research he did, the more he recognized bits of himself and his friends in the pre-homicide Cunanan.

Literary true crime tends to distinguish itself from the supermarket and airport gift shop variety by using the crime in question to illuminate some larger aspect of our world. For Indiana, the story radiates outward--his book is about both Cunanan and the media frenzy that surrounded him, and Three-Month Fever implicates our whole celebrity-deifying, money-lusting, gossip-strewn culture. The culture, in other words, represented by Vanity Fair, where Orth is a staff writer and where her version of the Cunanan saga first appeared.

Orth's book looks down at Andrew from on high, descending into his debauched world. Now, there's no reason why Orth, or anyone, shouldn't hate Andrew Cunanan, but her contempt precludes insight, since it supposes that he was so different from us upstanding citizens that there's no hope of understanding what went on in his head.

"No matter how much Andrew Cunanan got, he always wanted more--more drugs, kinkier sex, better wine. Somehow he had come to believe that they were his due," writes Orth. "And why not? He was always the life of the party, the smartest boy at the table. But at twenty-seven he was also a narcissistic nightmare of vainglorious self-absorption, a practiced pathological liar who created alternate realities for himself and was clever enough to pull off his deceptions. ... Lurking just beneath the charm, however, a sinister psychosis was brewing, aided by Andrew's habits of watching violent pornography and ingesting crystal meth, cocaine, and various other drugs so prevalent in some circles of gay life today--but rarely spoken of."

The books agree about the story's basic outline--Andrew Cunanan was a compulsive liar whose manic self-aggrandizement hid bottomless insecurity. Both follow Cunanan through his exploits in San Diego and San Francisco and both record the impressions of the same handful of friends. They concur about most of the facts surrounding his murders--that, his life in California having fallen apart, he had gone to Minneapolis hoping that his former best friend Jeff Trail and ex-lover David Madson would embrace him, only to find that both wanted him out of their lives. Neither writer disputes that the motive for these first killings was Andrew's rage when the two men rejected him. Each follows Andrew as he bludgeons Trail to death, abducts and then executes Madson, kills Chicago real estate developer Lee Miglin in his house in Chicago, murders William Reese for his car in New Jersey, then finally washes up in Miami Beach, where he offs Gianni Versace before committing suicide several months later.

But while the stories are similar, everything else about the books couldn't be more different. Indiana tries to come at the story from inside Cunanan's head, while Orth assumes the guise of a kind of forensic profiler and aligns herself with the police and FBI.

Three-Month Fever is stuffed with the cultural minutiae and psychological acuity of a good novel, humanizing Andrew without downplaying his crimes. Indiana forces readers to feel Andrew's desperation and humiliation, especially upon being rejected by the only two people he felt close to.

Journalistically, Three-Month Fever is far riskier and more suspect than Vulgar Favors. Indiana has stretched the new journalism/true-crime hybrid invented by Truman Capote and Norman Mailer--while they used fictional techniques, he simply uses fiction.

There are things in Three-Month Fever that Indiana couldn't possibly have known. "It isn't my desire to add word one to the 'true crime' genre, or to the 'nonfiction novel' a la Capote or Mailer," writes Indiana in his preface. "Three-Month Fever is a pastiche with which I would like to dissolve both of these unsatisfying modes, concerning as it does a story that is itself a pastiche, and in many respects inextricable from its own hyperbole."

Indiana admits that this passage was intended largely to head off a certain kind of review, one that would dismiss the whole book by challenging its reportorial ethics. And, indeed, this explanation sounds too easy and pat, since Three-Month Fever purports to be nonfiction.

Indiana's mode works, though, for a couple reasons--first of all, he usually alerts the reader to what he's made up, something that cannot be said for new journalists like Capote or Tom Wolfe. Beyond that, Indiana's hybrid is effective because even his more fantastical passages are grounded in solid reporting--he's immersed himself in Cunanan's mind, so his best guesses feel as close to the truth as we're likely to get.

"We don't really need to rehash these facts ad nauseam about when it happened, where it happened," says Indiana. "You have to have all that right, but what people really want to know, I think, is why this stuff happens and what kind of person does it and what would it be like. If a person leaves enough of a trail, you can get a really good impression. In Andrew's case, the trail was muddied everywhere and it took forever to sort out. I took my best guess knowing that I know the world that he lived in much better than any Maureen Orth will ever know. I think it was a big thrill for her to meet a homosexual for the first time when she started her research. I admire Capote and I admire Mailer too, but I didn't want to do it that way. I wanted to strictly adhere to the notion of nonfiction in certain respects and completely violate it in others."

Orth's book strictly adheres to the notion of nonfiction all the way through, but she manages to prove that facts don't equal truth. The reporting is usually scrupulous while the sensibility is horribly off. Thus even her smallest factual mistakes seem indicative of a greater cluelessness--when she identifies Seattle's well-known punkish alternative weekly The Stranger as a gay magazine, we're reminded once again just how out of it she is. Likewise, Orth attributes much of Andrew's homicidal breakdown to crystal meth use and has no trouble reconciling this purported addiction with his massive concurrent weight gain. "How do you gain 40 pounds on methedrine? I'd like to know," says Indiana, "because I used to take speed for 10 years and I never gained a pound--I was a skeleton. I don't know anybody who used crystal meth who ever gained an ounce. I mean, this stuff is nonsense."

Vulgar Favors tries to squeeze Andrew into the pop image of a serial killer, and Orth's descriptions often seem lifted from a particularly lurid episode of Millennium. Describing Lee Miglin's murder, she writes, "The sadistic aspects were consistent with a pattern prevalent among serial killers, whom experts say often need to act out their sadistic fantasies and repeat them until they get it right." Just a few pages earlier, Orth had already tied homosexuality and serial killing together. Enumerating other killers who had operated in Chicago, she adds, apropos of nothing, "Ironically, both [Jeffrey] Dahmer and [John Wayne] Gacy were also gay, and [Richard] Speck was bisexual--they just weren't out of the closet the way Andrew was."

Again and again, Orth links Cunanan's crimes to his fascination with S&M porn. She doesn't see the irony in repeatedly telling us that Andrew's favorite magazine, the one he read "religiously every month," was, of course, Vanity Fair.

Andrew's pathologies all had far more to do with money and celebrity than with sex--in fact, one of the most startling things in Indiana's book is just how rarely Cunanan slept with anybody. He wanted to be a high roller, not a dungeon master. We get a glimpse of some of Andrew's most detailed delusions of glamour in the letters he sent David Madson (quoted in each book) from a trip to Europe with a rich, much older companion whom Madson never knew about. "Avignon is still full of scamps and vamps, c'est moi, ne pas?" says one missive. Then, "Went to Monte Carlo and lost. O.K. Opera in Nice tonight was bitchin', Turandot, but tres avant garde. Food wonderful, company less so. Tomorrow AIDS rally-concert in Place du Ville. Tres cher, Drew." These notes are the ravings of a mind gorged on Conde Nast, not nasty videos.

Which, of course, is another irony--Orth sees evil in the queer underworld, while Indiana locates much of the trouble with Andrew in the chichi cloisters of mainstream gays who adopt and almost caricature the values of the straight world. "The stratum he wanted to move in was one that worships capitalism, worships financial and material success, is spiritually vapid to say the very least, and where appearances are everything. In the book, that woman that I don't name said, 'What other people thought of him was more important to him than life itself,' and to me that was the key to the whole thing."

More than just offering differing interpretations, these two books are situated in opposing moral universes. Vulgar Favors, in the end (and despite the writer's fancy pedigree), works with most of the same assumptions about good and ingrained evil found in quickie checkout-aisle schlock shockers, a world where there's an unbridgeable distance between the smug us and the depraved them.

Indiana's world is more ambiguous--for all its sophisticated wordplay and knowing references, there's a deep humanism to the book. "A lot of people who are ostensible spokespeople for this fictitious entity the 'gay community' came out and said very stridently, 'Andrew Cunanan is not typical of gay people.' I mean, who thinks he is?" Indiana says. "But then they said he's not one of us, which is why I put that quote in the beginning about 'his handwriting was identical with mine.' Of course Andrew Cunanan was one of us."

Vulgar Favors: Andrew Cunanan, Gianni Versace and the Largest Failed Manhunt in H.S. History By Maureen Orth Delacorte; 452 pages; $24.95 cloth

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

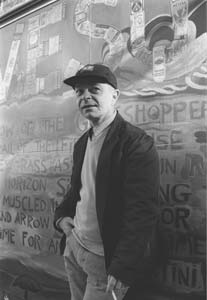

Killer Instincts: Writer Gary Indiana gets inside the mind of a murderer in 'Three-Month Fever: The Andrew Cunanan Story.'

Scrawled across my wall

I swear I can't repeat

The filthy words that I recall

And then the most immoral

Damned insulting thing of all

As I read each line I noticed

His handwriting was identical

With mine.

Three-Month Fever: The Andrew Cunanan Story By Gary Indiana Cliff Street Books; 254 pages; $25 cloth

From the May 13-19, 1999 issue of Metro.