![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Movies Index | Show Times | Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Puppet Show

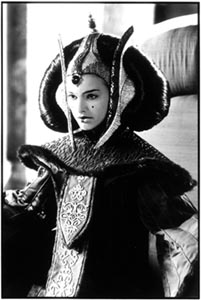

Photograph by Keith Hamshire

'The Phantom Menace' is more like a toy chest than a movie

By Richard von Busack

RICH AS DIRECTOR and writer George Lucas is, who'd want to be in his shoes? His Star Wars series is a focus for the inchoate longings for so many people. Anything he does with the saga is bound to rub at least a few million fans the wrong way.

Is it a surprise, then, that The Phantom Menace is such a cautious reiteration of the previous three installments of the epic? The new film is banal throughout. What it has are puppets by the score--it's more like a toy chest than a movie.

The theme is politics: the decline of the space republic. While the senate of that republic dithers, the lovely planet of Naboo is invaded by a federation. For pro-forma reasons, the federation needs the signature of Naboo's queen on a treaty to make their invasion legitimate.

Under the escort of a pair of Jedi knights (Liam Neeson and Ewan McGregor), Queen Amidala (Natalie Portman) is rescued and escapes to the capital planet of the republic to plead her cause. On the way, the group makes a fuel stop on the desert planet Tatooine, where they meet Anakin Skywalker (Jake Lloyd of Jingle All the Way), a boy slave who will later become Darth Vader.

But the political situation is hopeless. As commandos, our heroes return to Naboo for the battle to free the planet. The three-way climax restages and cuts together the denouements of the first three movies in the series: space battle (Star Wars), land battle of primitive soldiers versus modern soldiers (Return of the Jedi), light-saber duel in the interior of a power plant cooled with plummeting 1,000-foot ventilation shafts (The Empire Strikes Back).

Elected Royalty

The politics of The Phantom Menace are clouded. Queen Amidala lives in a colossal version of Italian Renaissance splendor. Gowned and powdered, she's painted like a kachina doll. But this vision of exotic royalty also informs us that she was elected to the throne.

The council of Jedi doesn't seem to answer to the senate or its grand counselor (Terence Stamp, in a cameo). Since blood tests determine whether a Jedi candidate is acceptable, it must be some sort of hereditary honor. (We already know, from the previous films, that Jedihood descends from father to child.)

Lucas' vision has always been top-down; there's royalty and then there are the peasants. (We hear that the people are suffering on Naboo, but we never see even one of them.) Does the authoritarianism of the Star Wars movies come directly from the samurai films--especially those by Akira Kurosawa--that Lucas used for inspiration? What I wish is that Lucas remembered what a physical comedian Kurosawa had as his reigning samurai star. The late Toshiro Mifune had a dry comic style. He had a body. He waddled a bit; in Yojimbo, he had fleas.

Has no one ever noticed what bores the Jedi are? Pious and righteous, walking around in their monks' robes with their hands folded--real knights and samurais knew courtly arts, but the Jedis don't seem to have social graces. They give off such an odor of sanctity that it must be like entering a joyless priesthood to join their ranks.

As the Jedi master Qui-Gon Jinn, Liam "Mr. Celtic Twilight" Neeson does seem to register some slight interest in a non-Jedi--the unattached mother of Anakin--but he leaves her without regret. (Her son leaves his mother with only minimal sorrow; the way Lucas handles the parting is shockingly bad. They say the main occupation on Tatooine is moisture-farming, but this scene doesn't raise even a tear. )

Qui-Gon's apprentice is the young Obi-Wan Kenobi, played by McGregor with a Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts accent. The sexless, bodiless quality of the acting is inevitable, since so much of the movie had to be played in a vacuum, to wait for the effects to be constructed.

The actors recite dialogue that sounds like subtitles read aloud ("You have brought hope to those who have none"). Keeping emotions flat is a way of standing back for the parade of the toys.

Among the toys, the prime one is the cute character Jar Jar Binks. He's a clumsy oaf, a sort of frog on stilts with a conical head who speaks a variation of pidgin Hawaiian adorned with lisps; and he grates on the over-12 viewer like an entire kennel of Ewoks.

The arrival of the robot soldiers, who come in racks like the action figures they are, is one of the movie's most interesting sights. So are the rolling artillery machines that unfold, stand and fire on their own.

But when you're praising the robots in a movie, it's as bad as praising the architecture. It's an acknowledgment that something human is missing. We could have used a place to stand for a second, a place to puzzle over the ideas of the movie--or to wonder how Lucas can reconcile the aristocracy with democracy, the arbitrariness of one and the frustrations of the other.

In making The Phantom Menace kid-safe, Lucas removed the mood that made his previous stories fascinating. The rumbling voice of James Earl Jones, well spoken and threatening, doesn't shade The Phantom Menace. The movie tries as its main villain Darth Maul, who is an assistant villain doing a prime villain's job. He's little more than a bloodhound following our characters. (His terrapin-face make up and horns has been marketed like Coca-Cola; they call him Maul because you'll be seeing him in the mall all summer.)

The demi-villain Anakin is never more than the unironic and uninflected kid hero. For someone who's going grow up to be Darth Vader, he's relentlessly sane. This is another movie of which it can be said: it's not over until the plucky little kid punches the air and says "Yes!"

The best poster for The Phantom Menace was a picture showing a child's shadow as the armor and cape of Lord Vader; there's no shadow here, just a singularly annoying kid. "He knows nothing of greed," says his mother, but as an actor Lloyd knows plenty about arrogance.

It seems that Lucas also doesn't know when he's overreached, nor does he seem to remember that his best efforts in this series involved collaboration with writers and directors. The "Eastern-like philosophy," as the press kit aptly describes the deep thought of the Star Wars series (the phrase is equivalent to "meat-like food") conflicts with the Western political thought.

The dark side of the inwardly looking philosophy is that it can align with fascism. After all, the Japanese general staff in World War II were all very religious, in tune with what they thought the Force was. What are the implications of power?

In this chaotic menagerie of toys and rockets and explosions, Lucas ducks the issues that might have turned The Phantom Menace from popcorn to genuine myth.

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![]()

The resolve of Naboo's young Queen Amidala (Natalie Portman) is put to the test by an invasion of her peaceful planet that embroils her in intergalactic politics.

The resolve of Naboo's young Queen Amidala (Natalie Portman) is put to the test by an invasion of her peaceful planet that embroils her in intergalactic politics.

The Phantom Menace (PG-13; 131 min.), directed and written by George Lucas, photographed by David Tattersall and starring Liam Neeson, Ewan McGregor and Natalie Portman, plays at theaters through the universe.

A web-exclusive to the May 13-19, 1999 issue of Metro.