![[Metroactive Arts]](/arts/gifs/art468.gif)

![[Metroactive Arts]](/arts/gifs/art468.gif)

[ Arts Index | Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Old Gods Waken

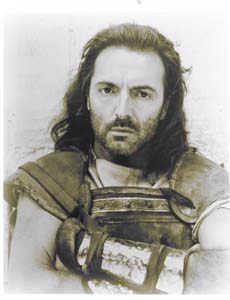

Man on the Move: Armand Assante's low-key, almost passive Odysseus finds himself adrift in a wine-dark sea of prose.

Why classical mythology is all the By Zack Stentz WHO SAYS the classics are dead? Just the other day when I was stopped at an intersection, a huge city bus pulled up next to me. Turning to look at the side panel advertisement, I found myself face to face with the ancient Greek hero Odysseus (Ulysses, for Virgil and Joyce fans), in a poster heralding NBC's upcoming miniseries of Homer's The Odyssey. "The greatest adventure story of all time," ran the tagline, and for once, the network that considers The Single Guy to be "must-see TV" wasn't exaggerating. Long before the first television producer sent his Armani-greaved minions scudding across the wine-dark freeways in search of literary properties to develop for May sweeps, oral recitations of Homer's works were thrilling audiences throughout the classical world. Following the unexpected ratings success of Gulliver's Travels last year (not to mention the economic advantages of adapting works in the public domain), H.G. Wells, Jules Verne and--God help us--Fyodor Dostoyevsky are all getting the miniseries treatment as the networks rush to embrace the Western canon in a way that should make William Bennett and Allan "closing of the American mind" Bloom weep in ecstasy. But is a televised Odyssey necessarily a boon to America's cultural literacy? "Oh, certainly," says Princeton professor Robert Fagles, whose brilliant new translation of Homer's original is a bestseller in its own right. "I've never seen an adaptation of Homer that didn't leave me richer in the bargain." Fagles might want to withhold judgment, though, until he hears some of the dialogue in NBC's The Odyssey. Neither faithful to Homer's text (70 percent of which, it should be noted, was spoken dialogue) nor fully colloquialized, as in Paul Schrader's The Last Temptation of Christ screenplay, the script by Andrei Konchalovsky and Christopher Solimine relies instead on the sort of mock-profound speech declaimed in posh British accents that was used to denote high seriousness in 1950s Bible movies. To get an idea of the end result, contrast Odysseus' televised rebuff of Calypso's offer of immortality--"I would rather lie in my wife's arms for one moment, as a man, than live forever without her"--with Homer's version (as translated by Fagles): "All that you say is true, how well I know ... nevertheless I long--I pine, all my days--to travel home and see the dawn of my return." "I'm sorry that the series is stronger on the visual than the verbal," Fagles says, diplomatically, "but I'll leave that to the television artists." And while a Kenneth Branagh or Morgan Freeman might be able to wring some drama out of lines like "You see, gods of sea and sky? It was I who conquered Troy!" the second-tier cast (Armand Assante plays Odysseus, Greta Scacchi is Penelope and Vanessa Williams shows up as the yummy nymph Calypso) is mostly adrift in this wine-dark sea of prose. Eric Roberts is the surprising and notable exception, as he turns his character, the oily suitor Eurymachus, into a figure of genuine charm and dread.

An Online Odyssey: The elaborate promo page by NBC. The text of The Odyssey online.

More about professor Robert Fagles and his

Five-Minute 'Iliad' SOME HOMERPHILES might object as well to the considerable sanitizing of the source material. Homer's Odysseus was a wonderfully skilled liar and a "raider of cities." Assante's Odysseus is a low-key, almost passive figure. When the program recaps the Trojan war in the space between two commercial breaks in a sort of "five-minute Iliad" (Greeks arrive, Hector takes a spear through the neck, Greeks build horse, Troy burns and now a word from our sponsors), we even see Odysseus feel bad for the Trojans he's exterminating, a notion alien to Homer's ruthless warrior-king. "What you've got to do upon entering the world of Homer is to park your Judeo-Christian values at the door," laughs Fagles, "because they will be infinitely confusing to you." Still, if Shakespeare could turn Achilles into a vicious bully and his climactic duel with Hector into a cowardly ambush in Troilus and Cressida, there's no reason why producer Robert Halmi Sr. and company can't take a few liberties of their own with Homer to make Odysseus more palatable to modern audiences. What's more vexing, though, is how the writers decline to avail themselves of Homer's wonderfully cinematic storytelling style, filled as it is with enough time shifts, multiple points of view and unreliable narrators to rival Pulp Fiction and The Usual Suspects in structural complexity. "It is richly cinematic," says Fagles of Homer's narrative technique. "The way the narrative plays with flashbacks and frames of reference would be the very envy of a David Lean, and not to capture that is an enormous loss." Fagles adds, "The miniseries is very linear, and Homer is not, and he's not for very good reasons. With flashbacks, you can re-evaluate past actions. And there's a reason why the first four books of The Odyssey are about Odysseus' son instead Odysseus himself. You miss the hero by virtue of his absence, and you learn about him through the reminiscences of other people--and above all, Homer is introducing the father by way of the son." Even in the program's most dramatic and visually exciting scene--the confrontation in the Cyclops' lair--The Odyssey's makers manage to miss the boat--or "black, swift ship," as Homer might put it. Odysseus' famously dissembling "My name is Nobody" statement is included onscreen, but the blinded Cyclops' cry to his comrades ("Nobody's killing me!") and their laughing reply ("If ... nobody's trying to overpower you ... it must be a plague sent by Zeus, and there's no escape from that") are not, effectively blowing the punch line to a very funny joke. (Homer's original is even funnier. The Greek term for "nobody" used by the Cyclops--me tis--is a homonym for metis, the word meaning "craft" or "cunning" and often used to describe Odysseus himself.)

Mythology Straight Up IF YOU START messing with the ancients to increase their mass appeal, you might as well go whole hog, which is why I much prefer the "mythology by mix-master" approach used on television's Hercules: The Legendary Journeys and Xena: Warrior Princess series. Both programs season their exceedingly free adaptations of Greek and Roman myths with liberal doses of anarchic action and campy, self-referential humor. The end product might not meet with Joseph Campbell's approval, but it certainly is entertaining, and both shows have turned into sizable hits in syndication. "I think the humor element is an important part of those shows' success," says television and film writer Robert Wolfe, whose own former series Star Trek: Deep Space Nine was recently overtaken in the ratings by Xena and Herc. "They've hit on a really fun way to reach audiences, by telling mythic stories with a lot of humor mixed in." Ironically enough, it was the genre's mythic aspects that drew Wolfe to science fiction in the first place (he's currently working on a Wesley Snipes television movie titled Futuresport). "Television science fiction is like mythology in that it gives us the ability to tell exciting stories against a dramatic, larger-than-life backdrop," he says. "We can consider grander issues--and have one person make a difference in a way that's difficult in a show about doctors or lawyers." It doesn't take a working knowledge of Bullfinch's Mythology to see how many recent science-fiction films and television programs have essentially told mythic stories in high-tech trappings (Star Wars or Babylon 5, anyone?). Now, though, audiences seem to prefer their mythology straight up, without the spaceships-and-lasers chaser to which they've become accustomed. And despite their anachronistic touches and weaknesses in execution, these programs draw viewers on the basis of the power of the original stories on which they are based. And the turning of that original spouse-killing, 'roid-rage sufferer into a blond, muscle-bound Boy Scout nonwithstanding, look for this summer's Disney-animated Hercules film to be a huge hit as well. We may not be heading for an entertainment landscape like the one that exists in India, where the Mahabharata, The Ramayana and other sacred texts are bestselling comic books, blockbuster movies and ratings-grabbers on television. But as The Odyssey and Hercules prove, we don't need William Bennett to spoon-feed us culture because it's virtuous, nutritious and high in unsaturated moral fiber. The classical myths that form the foundations of Western Civilization are good enough stories to sell themselves, and hold their own against the John Grishams and Danielle Steeles of the world.

The Odyssey shows May 1819, 911pm on NBC. [ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This page was designed and created by the Boulevards team.

Copyright © 1997 Metro Publishing, Inc.