![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)

![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Movies Index | Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Cannes Doings

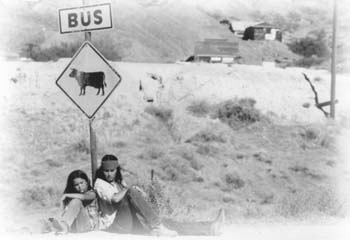

Vanity, Thy Name Is Cinema: Inspired by the murky symbolism of Jim Jarmusch's "Dead Man," Johnny Depp dons red face and directs himself as a Native American stud and metaphoric stand-in for America's first oppressed peoples in the ridiculously inept neo-Western "The Brave." Our man in the south of France surveys the good, the bad and the ugly at the world's most famous film festival By Rob Nelson THE CANNES FILM FESTIVAL is defined by the most extreme contradictions: culture and glamour, art and commerce, critical debate and crass deal-making, challenging cinema and mainstream product. Such dichotomies seemed encapsulated by this year's closing film: Clint Eastwood's Absolute Power, an artful studio movie by a Hollywood moneymaker and hallowed auteur, a critique of absolute power and the thing itself. But Cannes also makes room for the likes of Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami's The Taste of Cherry, a gorgeously minimalist character study of a man's consideration of suicide. The film shared the Palme d'Or with The Eel, a gently quirky melodrama directed by Japanese master Shoei Imamura. These two worthy winners might be cited as proof that a movie's inclusion at Cannes is an indicator of quality, but most of the 19 movies screened in competition this year left a lot to be desired. Still, befitting the 50th-anniversary spirit and the near-pathological obsession with cinema that engulfed the Cote d'Azur for the last two weeks, several pictures purveyed a critical take on the industry--or at least returned the media's gaze. Albeit unfunny, the Argentine comedy La Cruz (The Cross) resonated with the working press because of its main character: a psychotic film critic (Norman Briski) who gets fired for writing too many negative reviews. Out of a job, the critic nevertheless tells a friend that he's planning to attend the next Cannes festival. Speaking of beleaguered journalists, two events centered on The Blackout, Abel Ferrara's salacious portrait of a Bad Lieutenantstyle Bad Actor (Matthew Modine), managed to hit critics where they live. A mosh pit in front of the tiny Cinema des Arcades caused one faint journalist to experience a literal blackout, while Modine's press-conference request for a black British critic to repeat his question because "it's dark in here" prompted the writer to accuse Modine of racism. (Ferrara responded to this charge in typical Bad Director form: "I've seen his type selling cassette tapes for 20 bucks in Rhode Island.") Meanwhile, The Blackout itself proved another of Ferrara's intense trips through the gutter of Catholic guilt and insatiable addiction (and cinematic self-reflexivity). At the other end of the art-film spectrum, Jean-Luc Godard's latest project, Histoire(s) du Cinema (parts 3A and 4A), is another enjoyably inscrutable inquiry into the question "What is cinema?" Using pilfered clips from Hitchcock and Italian neorealists to metaphorically wrest film history from its copyright owners, the former Cahiers du Cinema reviewer goes on to suggest that anyone with a VCR and a remote control can (and should) be a critic. The plural histoire(s) in Godard's title seemed to reflect the many diverse histories in the making at Cannes--encompassing everyone from Godard to, ugh, Luc Besson (whose The Fifth Element opened the fest in faux-epic fashion). The vast gulf between these two auteurs could be measured by the fact that Godard's press conference was, shamefully, only poorly attended, while French celebrity Besson was greeted with shrieks of "Luc! Luc!" every time he crossed the Croisette. In a way, The Fifth Element seemed the perfect Cannes opener: articulating the insidious Planet Hollywood mentality that provided at least half the plot here, and proving that a French director could make a big-studio blockbuster with no less an icon than actor/restaurateur Bruce Willis.

SIMILARLY, but on a lower budget, the French would-be wunderkind Mathieu Kassovitz scraped the scummy bottom of Tarantinoesque Americanisms with Assassin(s), a repulsive and plagiaristic hit-man thriller that inspired vindictive boos. It's clear that Cannes isn't immune to dilettantism. In fact, actors Johnny Depp and Gary Oldman were somehow allowed to make their directorial debuts with films in competition. In Depp's ridiculously inept neo-Western The Brave, the actor practically dons red face for his role as a Native American stud who submits to death by torture in exchange for reparations from an old sadist (Marlon Brando, playing Col. Kurtz once again). Meeting the press, director Depp had the gall to suggest his film as a modern metaphor for the genocide of Native Americans. Somewhat more authentic was Oldman's verité-style Nil by Mouth (co-produced by Besson, of all people), which portrays south London family squalor through such characters as a monstrous lug (Ray Winstone) who regularly beats his faithful wife (Kathy Burke) to a bloody pulp. Beating the viewer over the head, Oldman includes "Can't Help Lovin' Dat Man" on the soundtrack and gives the abusing husband a didactic soliloquy explaining that he himself had been hit by his dad. Like so many first-timers, Oldman uses excessive violence mainly to show that he means business. (Sony Pictures Classics took the bait in this case.) Another act of assault-as-showmanship was perpetrated by Austrian director Michael Haneke, whose family-under-siege thriller Funny Games is one of the most disturbingly sadistic films I've ever seen. Like Wes Craven's Scream, it winks at the viewer about how cleverly it's overturning horror conventions while basically preying on our sympathies and cultivating real-world fear. Conversely, Cannes favorite Wim Wenders gave his latest work of techno-pacifism the pretentious title The End of Violence. Amounting to an arty but equally insufferable version of Grand Canyon, it's an L.A. story that focuses on a producer of violent movies (Bill Pullman) who gets a taste of his own medicine when he's compelled to offer his kidnappers a million dollars--in percentage points. (Ironically, Wenders himself was attacked at Cannes by two masked thugs who attempted to steal his car; unlike his character, the filmmaker gave chase, but the thieves got away on a motorcycle.) Wenders, with his healthy budget and hip cast (Pullman, Andie MacDowell and Gabriel Byrne), joined Besson and Ang Lee in delivering an overwrought and underdeveloped American film. (Lee's deadly dull The Ice Storm, with Kevin Kline, Sigourney Weaver and Joan Allen playing pent-up East Coast parents in the early '70s, merely aspires to the somber WASP melodrama of Ordinary People.)

The official Cannes site in French. An English Cannes site. Cannes netcasts.

UNEXPECTEDLY, one of the more satisfying movies in competition turned out to be L.A. Confidential, a big-scale Hollywood genre film based on the James Ellroy novel and directed by the heretofore hacklike Curtis Hanson (The River Wild). Set in the 1950s, and featuring Kevin Spacey and Kim Basinger in what amount to minor roles, L.A. Confidential is a noirish cop thriller that recalls De Palma's The Untouchables in its sharply edited shootouts, snappy dialogue and confident use of two unproven hunks and soon-to-be stars (Russell Crowe and Guy Pearce). Another surprise was that Michael Winterbottom's Welcome to Sarajevo, which had been hyped from the fest's first hours as the likely Palme d'Or winner, turned out to be a facile and familiarly rendered drama of Western journalists (Woody Harrelson, Stephen Dillane) struggling to reveal the truth of a distant war to an uninterested audience back home. Winterbottom (Butterfly Kiss, Jude) continues to expand his dramatic range with this, his third film, which is powerful insofar as it includes some real footage of Sarajevan concentration-camp prisoners within its Oliver Stonelike visual blitzkrieg. Otherwise, the mix of hand-held video and wide-screen Steadicam shots is off-puttingly slick--as is the "ironic" use of cheery pop songs like "Don't Worry, Be Happy" and the predictable lack of native Sarajevans as major characters. Ultimately, the film's point--that representations of difficult subjects need sugar-coating to get over--is made more unintentionally than not. In the midst of this curiously underwhelming lineup, it was fortunate that such reliable masters as Wong Kar-Wai (Happy Together) and Atom Egoyan (The Sweet Hereafter) came through with films that mostly met their high expectations. Egoyan intrigued his many fans by showing more emotion than usual in his intricate adaptation of Russell Banks' novel. Like last year's Palme d'Or winner, Secrets & Lies, The Sweet Hereafter is a tale of family turmoil dredged up and laid bare, as a repressed big-city lawyer (Ian Holm) swoops into a small town in British Columbia to seek settlements for the grieving parents of 14 children who died in a bus accident. In a typically complex Egoyan narrative, we discover that Holm's character has loved and lost one of his own brood, too. Egoyan was criticized in some quarters for failing to tie up thematic loose ends, but I'd say that further supports his ambitious bid to make his oeuvre a little messier and more true to life. The ratio of strong films to weak might have improved further with the presence of Zhang Yimou's new Keep Cool, but this was not to be. Just as the New York Film Festival was nearly denied permission to screen Zhang's Shanghai Triad because of the Chinese government's objection to another picture (The Gate of Heavenly Peace), here a Chinese film about homosexuality called East Palace, West Palace provided the pretext for China's ban on Keep Cool. This situation was all the more disappointing in light of the fact that Palace played like a timid and didactic Kiss of the Spider Woman knock-off, in which a gay man (Si Han) explains his sexuality to a homophobic cop (Hu Jun)--the latter being a surrogate figure for the perceived mass audience. China's hostile reaction to the film bears out its degree of risk. And in this way, East Palace, West Palace provided a worthy object lesson: Given the serious threat to world cinema being posed by imperialist Hollywood, any movie that distinctly reflects its country of origin is worthy of respect. [ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This page was designed and created by the Boulevards team.

Copyright © 1997 Metro Publishing, Inc.