![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Generation Exiles: Matt Taibbi and Mark Ames have gotten death threats in Moscow for their 'expat' tabloid called 'the eXile,' but they continue to publish.

Generation Exiles: Matt Taibbi and Mark Ames have gotten death threats in Moscow for their 'expat' tabloid called 'the eXile,' but they continue to publish.

Trenchant Warfare! How a kid from the Silicon Valley suburbs made Moscow squirm By Mark Ames

When a local attorney's kid stopped by Metro's office sometime in the early '90s for some pointers on how to publish a newspaper, the mild mannered Saratoga-raised UC Berkeley grad dropped no clues that he would emerge as a controversial and internationally significant satiric journalist with titanium testicles. With the pranksterism of '80s-era Spy magazine, the wit of The Onion, the drug-addled rage of Hunter Thompson, an O'Rourke-esque appreciation for the absurd and the bravado of witless war correspondents, Mark Ames and Matt Taibbi have taunted Moscow's petty thieves, mob thugs, corrupt politicians and lying journalists in the pages of their English-language publication, the eXile, since 1997--and lived to write a book about it. Excerpts from Ames' chapters are published here. Obviously, the heroin-fueled fleshpot of Moscow gives rise to passages that some readers may find shocking. Rest assured that we toned down some of the lewdest parts to appease the delicate sensibilities of suburban readers who feign offense to our back-of-the-book sex ads while reaping the economic benefits of the valley's porn-fueled economic prosperity. Others may want to pick up a copy of "The Exile: Sex, Drugs, and Libel in the New Russia," by Ames and Taibbi (Grove Press), which is available at better bookstores.

--Dan Pulcrano THE EXILE WAS THE PERFECT name for our newspaper. I consider myself an exile from California. I wasn't forced out of my homeland in the classic, victim-of-tyranny way, but I was forced out nonetheless. "The eXile" also carried an ironic meaning, especially considering that most Western expats in Moscow spend their off-hours whining about the lack of Western conveniences, the surface ugliness of the Soviet architectural remains, the vulgar decadence of the new rich, the lazy and unreliable work habits of the natives, the rude service--everything that their cozy native lands trained them to resent. There is also a very un-humorous side to the word "exile." To most Russians, few words conjure as much tragedy and cultural/historical pain. Most of the great figures of Russian literary and philosophical history were forced into exile, from Pushkin to Lenin to Solzhenitsyn. The entire aristocracy, what was left after the butchery and counter-butchery in the Civil War, was exiled. With Stalin, exile was socialized, taken to the masses. It didn't matter how clever or rich or dangerous you were--all were welcome! Entire nations were exiled: the Crimean Tatars, the Chechens, Volga Germans, Baltic peoples, Jews ... And here we were, a pissy, free, biweekly English-language newspaper, selling the national tragedy as a joke. Two weeks after I moved to Moscow, Yeltsin disbanded the parliament and civil unrest began. By chance, I happened to move to a dirty little apartment only five bus stops from the White House. The administrative parliament in my district, Krasnopresnensky, voted to side with the rebels. That meant I was living in rebel territory, in the very center of the Russian empire! A week later, it snowed. Snow in September! I lived in a dirty Kruschev-era apartment building, one of zillions of block-buildings planted as if haphazardly on any open piece of land in Moscow. There were no suburban zoning Nazis in Moscow. Just build 'em where you can! My neighbors warned me about the Azerbaidjani refugees, who'd jump and mug me if they knew I was an American. They were ashamed of the decaying state of their apartments. The courtyard was a mess of weeds and ditches with exposed pipes, and a broken monkey-bar set. "It must be so much more beautiful in America, in California," the old Tatar woman next door would tell me with a mixture of sadness and shame. But it wasn't. This was the life that I dreamed of. While the few expats I knew sneered at how the Russians fucked everything up and spoke of Western beauty--the kind of familiar, clichéd beauty of European travel books and suburban development brochures--I treasured these sites, these Socialist ruins. And then it snowed--in my neighborhood, covering the monkey bars and the sickly birches and the courtyard blemishes. In September! A week after that, in my very own neighborhood, civil war broke out. It started on October 3rd, my 28th birthday. The rebels stormed out of the White House and seized surrounding territory, disbanding and beating Yeltsin's riot troops. They fanned out from the Novy Arbat, down to Smolenskaya Ploschad, then raced down to the Ostankino TV tower. I was watching the television as the battle there began. The announcer was terrified. And suddenly, just the way it happened in Dawn of the Dead, my TV went blank. The old Tatar woman from next door invited me over. She couldn't stop crying. I couldn't understand a word she said. She had a full set of metal teeth that wouldn't stop crunching. Through those teeth, she went on about World War II, I think ... something about having to evacuate Moscow to Kazan ... her dead husband ... That night, I could barely sleep. It wasn't just my birthday--it was as if I was finally born on that day. Dreaming of Olga I WAS A STUDENT at Berkeley in the late Reagan years. We had a lot of ideas back then, big dreams about getting famous and destroying the "Beigeocracy" that we thought stifled and controlled American Letters. Everything seemed possible then: world war, literary fame ... Anyway, something Really Big, with us at the center of it all. We'd ridicule the boring lefties, our enemies. We'd drop all sorts of drugs and go to the underground shows: Scratch Acid, Husker Du, Sonic Youth. It felt like something might happen, and soon. Then something happened. As in, nothing happened. At all. And then I graduated. The Bush years marked my decline, the Fall of my empire of dreams. When Bush and his golfing buddies got tossed out in '92, I started thinking, hey, Bush and I have a lot in common. Except in one small respect: Bush was a filthy-rich historical figure, whereas I was an unemployed, barely-published, aging zero. I began to notice something during those years of sliding insignificance. Strangely enough, even though I lived in California, the yardstick by which all cultures in the world measure themselves, my country was, paradoxically, becoming increasingly inaccessible to me. I felt more and more foreign as the months went by. I took a belated trip to Europe, which included a two-week stay in Leningrad, just after the failed August coup in 1991. That 14-day Homeric adventure on the streets of Leningrad really made an impression--I briefly fell into a world of prostitutes, pimps, petty thieves and high embassy officials who had to fight with the OVIR police to extend my visa and allow me to leave the country. Several months after returning home, my slow-working mind began to process it all. I didn't yet realize, consciously, that I belonged in Russia. So instead of staying in Leningrad, I returned to the Bay Area in late 1991. I'd contracted an epic case of scabies sometime during my vacation, an infestation that would define the next nine months of my life. I spent almost an entire year holed up in Foster City, a decaying 1970s suburb built on landfill, staying in a home where my Czech emigre girlfriend and her mother lived. They'd turned the back wing of their house into a care home, and named it "The European Care Home." It was about as close to Europe as I dared to move. At this point, I'd like to take you on a little tour of suburban California. By reminding you of the bland hell that exists before your eyes on a daily basis, you will better understand why I defected to Russia. Foster City was a scary place, even by suburban California standards. On the west side, closest to Highway 101 and San Mateo, Foster City had a cluster of '80s-style 10-story iridescent-green glass skyscrapers. It was the result of a failed attempt to remake Foster City from a commuter suburb to a high-tech center. Foster City was neither high-tech mecca nor residential dreamland. You saw it when you drove past the half-abandoned mid-rises, and into the one-story, residential eastern half, closer to the bay. Every garage seemed to have a second-rate sports utility vehicle with "Ross Perot for President" bumper stickers plastered on the bumpers or on the smoked hatch windows. This was the "angry middle class," and they didn't look all that angry to me: just dull and stingy. In spite of the constant heat, you never actually saw people. And even when you did, they avoided looking at you. They'd check their mail or work on their cars while listening to classic rock. But they'd never look at you. Meanwhile, my scabies infection only got worse. It baffled the doctors. First I was told it was a simple rash, and prescribed Cortisone. I'd squirt the white cream on my ass, but the relief was only temporary. As I later found out, there's nothing scabies mites love more than Cortisone-treated skin. It makes the flesh softer, chewier. Applying Cortisone was like tilling the soil: all the mites had to do now was fuck, and they'd create one of the largest human scabies settlements on planet earth. And fuck they did. When I couldn't stand the itching anymore, I took my ass to another doctor. He diagnosed me with scabies, so he gave me a tube of Elimite. It was like napalm. I couldn't tear my skin off. I was like that Vietnamese child from the war posters, crying and running naked down the rice paddy avenue, only I wasn't in a rice paddy, and no weeping hippie was going to hold up an anti-arachnid protest placard of me scratching myself. I almost never left my bedroom. I'd read Russian novels, dream about that two-week vacation in Leningrad, about the street punks I'd hung out with during that two-week incursion, or the girl, Olga, who became my temporary girlfriend and with whom I'd traded love vows. Olga, the half-Estonian, petite redhead. We met at some metalhead's party on Vasilyevsky island. She asked me to dance, which was strange. But I danced with her anyway. The next time we met there, Olga took me into the corner for sex. My friends were in the same room; the "bedroom" was really just a corner of the room partitioned off by some cheap shower curtains. He and his friends blasted his television on the far side of the room while Olga and I fucked in his bed. I think I caught the scabies from her. One thing I learned about Russians during that vacation was that they made every day count. They weren't looking to relax in front of the television and watch ESPN and talk about their mutual funds and eat at ethnic restaurants. They were looking for action. It seemed as though there, in Leningrad, in 1991, things were possible. It was so alien, and yet, I felt more at ease there than anywhere I'd ever been They didn't oppress you with their pod-people smiles and affected self-confidence the way they did in California. In fact, they looked every bit as miserable as I'd felt inside for, oh, as long as I could remember. My first aborted attempt at fleeing California was a nine-month stint in Prague, from mid '92 to early '93. Prague sounded like a great option: it was cold, alien, polluted, lumpenprole-ish, and yet European. I even didn't mind working a "job" there to make money. My girlfriend and I had cooked up a few schemes. We were going to import used, broken cars from West Germany, fix them up using mechanics from Nova Poka, in Northern Bohemia, then re-sell them in Prague for a profit. The whole thing seemed fool-proof. I bought a Berlitz book to learn Czech. I read up on the history. It didn't compare to Russia, but I tried to be enthusiastic. I began imagining myself, anonymous, wealthy, bundled up in sweaters and an overcoat and gloves ... Cold, alone, wealthy. That sounded nice. I'd be able to write in peace. It would be a kind of minor epic exile. Lonely, true, but at least, I'd finally get away from the country that gave me so little.

SOMETHING ABOUT PRAGUE didn't quite jibe with the intelligence reports I'd submitted to myself back in Foster City. For one thing, there were tourists everywhere. The more I looked, the more I was shocked. Then the shock turned to terror. I was sure that I even saw American students. Must be tourists too, I thought. But I was wrong. Half of America's youth had already moved to Prague before me. They'd scooped me. There were an estimated 30,000 young, nose-ringed, torned-jeansed English-speaking students squatting in the center of Prague, and there weren't a thang I could do about it. I'd come there to make a quick, hot buck with my Czech girlfriend, and wound up getting squeezed out by grunge-hippies half my age. It was as if they'd taken a huge needle, sucked the genetic material out of Foster City, and injected it straight into the nucleus of Prague. As for the Czechs: mere groveling Uncle Tomases, West German wannabes. My obsession with Russia only grew. The difference between Prague in 1992 and Russia of 1991 was the difference between some silly art house film and Terminator. I'd tell that to the few bohos I met, and they were shocked in a condescending way: why would anyone want to go to Russia? was their unanimous reaction. That only made me more determined--because I realized that, if everyone in Prague shuddered at the thought of heading to Russia, where the people were cruel and savage and gunning each other down in the streets, where food couldn't be found and phone calls couldn't be made, then that would mean these people WOULDN'T BE THERE! I took it out on my girlfriend. Her used-car scheme fell apart. Her mother had run off with an abusive ex-boyfriend from Germany. I resented her and her insignificant dump of a country. She was no angel herself. Nearly every Vaclav in town was tapping into her the second I'd turn my back. I even met a few of them. One had a ponytail and tried emulating the American grunge-hippies. Another bragged about his Audi car and the shopping sprees in Stuttgart. I dumped her and moved out on my own, into a dark, ugly apartment that reeked of urine and old tea. I'd go out to teach English to Czech businessmen. They wanted to impress upon me how Westernized they were, which made me loathe them even more. They all stank of beer and cheap deodorant. Then I'd come home and dream about Russia: violent, sexual, chaotic, too authentic for these fucks. Russia had become legendary in my mind, the more my own life diminished. The memory of those two weeks in Leningrad transformed into epic poetry: the all-night drinking and pot-smoking, the young petty criminals who took us into basement hangouts for more pot-smoking, the beautiful girls in their cheap clothes, sitting quietly ... Russia was the anti-matter that the physicists of my mind had been searching for all those years. Moscow Life and Times IN MOSCOW, a startup newspaper called Living Here offered me a job as their feature columnist. The main expatriate newspaper, The Moscow Times, had just printed an old article of mine, "The Rise and Fall of Moscow's Expat Royalty," which caused a minor scandal among the colonialists. Living Here didn't really have any direction, but they thought that if I wrote more articles like that, they'd at least have some readers. Living Here was an accident. The idea for starting up a third expat newspaper in Moscow to compete with The Moscow Times and The Moscow Tribune came from Manfred Witteman, a failed Dutch musician who had spent years slogging around the Moscow Times' offices, fixing computers and playing the feckless alcoholic comic relief. Somehow he convinced his 23-year-old ex-girlfriend, Marina Pshevecharskaya, to pony up $10,000 to start up a newspaper. Marina was a classic "Westernized Russian," a squealing suck-up to any expat. Marina drove a Volvo and hung out at expat parties. She made her money quick and easy, acting as an agent for expats seeking apartments. She'd take a month's rent in commission, in a city ranked as the third most expensive city in the world, after Tokyo and Osaka. Living Here was originally conceived as a real estate and community newspaper for expatriates--that way, Marina would get an immediate return via free publicity for her agency--but the idea was lame, and it fizzled. Under me, Living Here transformed into both a sniper's nest from which to pick off personal enemies, and an irresponsible chronicle of everything vulgar and grotesque. The one thing Living Here aggressively lacked was straight journalism. I had a prejudice against the very concept--and I was too lazy to give it a go. The newspaper was a totally uncensored, sloppy, irresponsible take on the violent culture of modern Moscow. Since no one covered that side of the story--everyone was too interested in top-level politics and economics--we wound up claiming a little chunk of turf. I was pretty sure there was nothing like Moscow in the world. Everyone who lived here felt that; and yet, for some reason, the official Western-reported version of events always made it seem more familiar than it really was. Simple, decent people's struggle to transform Russia into suburban California. You only dreamed of places like this back in California. You listened to your Lou Reed albums and read your Philip K. Dick books and watched Blade Runner, trying to scrape some of the experience off the edges of the medium. But from out there, in the flattest, cleanest, most comfortable coastline on earth, a Moscow wasn't even imaginable. The only Moscow imaginable was the Moscow as measured by the American/European yardstick: how close or far, and at what rate, Russia was approaching Palo Alto. Office Sweet WHEN I LEFT Living Here, I hooked up with their last sales manager, a young American named Kara Deyerin, and her Jell-O-spined boyish husband, Marcus. Actually, only Kara was my official partner. Marcus was too much of a community college moron, and Kara ruled over him with an iron fist. He was an invertebrate, a disgrace to the male gender. He'd sit in our meetings, hands clasped thoughtfully in prayer, then suddenly blurt out, "Why don't we try ..." He even began making editorial suggestions. In his view, we should appeal to everyone, give all points of view, and reach out to the community more. When Marcus even opened his mouth, you knew that the next 20 minutes were gone forever in the waste bin of time. Kara finally banned her husband from attending our meetings. She'd send him on errands instead. It was embarrassing. They came to Moscow with dreams of opening up a Seattle-style coffee shop, the kind where you have open-mic readings, to the background of world beat music or some lesbian folk singer ... Part Indigo Girls, part Friends ... A quaint dream that died along with the tales of other dead dreamers in Moscow, all those stories of expats who'd had their businesses requisitioned by bloodthirsty flatheads and Chechens ... Kara, with her squat, hirsute body, was no catch. It's not as though there weren't options, even for Marcus. Moscow is packed with more female beauty per square mile than any place on earth. And not haughty, cold types, but inviting, curious beauty, always looking to try something new, trade up, succumb to pressure, fall into some wild and unexpected adventure ... You catch their eyes on the streets, something that doesn't happen in America. Femme fatales on every sidewalk! Vixens riding down the metro escalators! Sly seductresses pouring into the streets! Somehow Marcus managed to block that part of Moscow out. We'd often ask ourselves how long he could deny the yawning beauty gap between his wife and, well, just about every single girl in Moscow ... A few months after we started the eXile, Kara invited an acquaintance of theirs from the Midwest to come to Moscow and take over as sales manager. Paul had a ridiculously innocent, puppetoon face: bright red lips, twinkling eye, greased back hair--'80s Wall Street hair ... Paul was a monstrous failure as sales manager, but not bad at trying to fuck the entire Russian female staff at the eXile. His first target was our sexy receptionist Yulia, a half-Estonian 20-year-old with honey-colored hair and big green eyes. He started off by trying to charm her, and she led him on with her inviting laugh, one hand on her chin, big green eyes looking up. From down the hallway, you could hear Paul chortling, like a barking seal during mating season. Within a month, he was literally chasing Yulia down the hallway to try to get her to kiss him. Once, Yulia screamed for me to help her. I had to pull Paul off and lock her in our publisher's office. I blocked the door and told Paul to calm the fuck down. "I love Moscow, man!" he'd wheeze with that hand-in-the-cookie-jar expression of his. "Man, you can do anything here!" Kara and Marcus had to watch this every day: eXile guys chasing women in the office up the walls, into stalls ... Paul fucked the first sales girl he hired, Lyuba, a silicon-lipped 19-year-old blond. She quit a few weeks later. He fucked our production manager, Tanya. He fucked a married card dealer from one of the casinos that he'd landed as our client. He fucked a neighbor of Kara's. He fucked everyone, that is, but his ex, Kara. With her, you just asked for money. Paul was such a failure at sales that even Kara couldn't hide it. He was finally given the boot. He headed back home to America, but first, he pocketed a thousand eXile dollars from an overdue client, and spent them on cards and whores and coke.

Amazing Johnny Chen ABOUT A MONTH after we launched the eXile, I started getting a call from some kind of nervous American nerd asking how he could contribute to the newspaper, since he was a big fan. He stuttered when he spoke to me; he tried to drop hip expressions, but they came out wrong and forced. I did my best to put him off. I have a terrible prejudice about writers who cold-call me--I assume that they must be worthless if they're crawling up to me. It's the same tried-and-true formula that has led to a disastrous record in the field of long-term relationships with girls: if she wants me, something must be wrong with her. This guy had sent a letter to our [sic] page, a place for readers to submit themselves to open abuse in exchange for an eXile T-shirt, and signed his name "Johnny Chen." I thought the name was a joke or a pseudonym, since few people sent us letters using their real names. About a month after that, he called me again, and asked if he could pick up his eXile [sic] T-shirt. I told him to come by after work that day, so that I would miss him. Another fear of mine is that anyone who comes to our office has one intention: to murder me for things I've written. Then disaster struck the eXile. Owen, who wrote club reviews for us under the pseudonym "Robert Plant," got worse and worse as a writer. Not only did he never get his pieces in on time, but he even wrote reviews on clubs and bars that he never visited. And every piece was the same: Russian-managed bars sucked and lacked taste, and Western-style clubs were signs of hope. Readers complained. Just as Taibbi and I were trying to figure out what to do, I got another call from Johnny Chen. "You never answered me, Mark. Just tell me yes or no. Don't you realize that you're passing up an opportunity?" I looked through the bars in our window, across the courtyard, and up to the roof. We were located on the ground floor of a residential apartment block, a horseshoe of eight-story buildings. This crazed gook's probably Oswalding me from the roof across the way, with a cell-phone and a scope-rifle. "Look, I understand your newspaper better than anyone," he went on. "It's basically Revenge of the Nerds. But you guys aren't the real thing. I've seen you and Taibbi--you look like a pair of wrestlers. You guys aren't the real thing, you know. I am. I can give you an authentic dweeb's view of Russian nightlife. All I ask for in exchange is one of your eXile press cards you guys have, so that I can get into clubs and stuff free, and use it to impress girls. In return, let me write your club reviews. Let me at least try. Your Robert Plant guy sucks, and you know it. Everyone I talk to thinks he's a joke, and you're losing cred. But just think: what newspaper, anywhere in the world, would ever hire a 31-year-old Asian-American like me, a fucking Information Manager at a Big Five firm, to write their club reviews? You guys are always trying to buck convention and stuff, and you try to be hip by being unhip: well, here's your chance to make nerd history. Think about it: if it can be proven that a guy like me can get laid and have a wild nightlife in Moscow, then literally ANYBODY can. That's what I tried to tell you in my letter you never read." Column Power GOD DAMMIT, he was right! I mean, only if he could write. But fuck it, even if Chen couldn't write, we'd use his persona, publish his picture, and edit the hell out of it, just to bring the Moscow Decadence myth to a new level. His first review was about a disastrous evening out to a strip joint called Rasputin. The short Chechen club manager was so sure that Chen was a fraud posing as a journalist that he set him up. He sat Chen down at a barstool and motioned one of the girls to join him for a drink. When the aging red-haired stripper-whore sat next to Chen for some light conversation, she ordered a glass of champagne, then later walked. The barman presented the Chenster with the bill: $150 for the glass of champagne, $20 for each gin and tonic that the manager had offered him. Chen threw a fit. He told them he was leaving, like it or not. They could take him out back and beat him, but he wasn't going to victim to a shit Bangkok scam like that. For some strange reason, they backed down, an example of the kind of luck that Chen has had ever since moving to Moscow. When he came into the office to deliver his Rasputin piece, I was shocked at whom we'd hired as our Voice Of Hipness: Chen's longish, parted black hair, square wire-rimmed glasses and beige corduroy pants, and a slight pigeon-toed slouch, spoke of years of half-heartedly masturbating by the computer table. In person, he was much shier and tongue-tied, although on the phone and in print, his voice reflected at least a good working knowledge of coastal California slang. Chen started living up to his promise as the approaching-middle-aged-nerd who shamelessly groped his way into corporeal heaven. He abused his press card as much as possible. He'd flash it in everyone's face, and it paid. At first, I thought his tales of sexual conquest were exaggeration, but once, I saw him at a club crudely French kissing two teenagers. They weren't cute, but they were alive. I found myself even getting sort of pissed off. The bastard! Leeching off our sweat and tears for his cheap thrills! Then Chen started dabbling in heavy drugs. Dabbling? More like Hoovering them off anyone and anything he could find. When Chen came into our offices, we had to hide everything. Piles of phenamine, normally sitting out by our computers on production night, would suddenly be locked into the cupboards. Even our female sales staff hid. Later, it was Chen's famous "rape" review of a club, in which he allegedly wrote about how he raped a girl who'd fallen off the bartop at the Hungry Duck and into his arms, that sparked Stanford professor, Carnegie Endowment honcho and Clinton administration tool Michael McFaul to begin his official ban-the-eXile campaign. Chen made headlines in every Russian-studies academic's Internet mail programs. He became the subject of heated exchanges between journalists, and the focal point of a First Amendment debate. Chen ate the publicity up. "Russian girls get really excited when they see your name in a newspaper," he told me. He'd carry laminated copies of the articles with him into clubs and show them off. "I'm really glad that McFaul jerk attacked me. I've never scored so much pussy in my life!"

The Paradigm Strikes Back SOMETIMES I WONDER if I've betrayed my own revolution. Is this what it was all about? Is this why I paid all those years? Just for sex and drugs? Well--yeah, what the fuck! And lemme tell ya: The People in me are grateful. Grateful for The Revolution that freed them from the bonds of American banality. They're marching in formation down Red Square, having replaced "Land, Bread and Peace" with "Sex, Drugs and Fame." And "Death to the Paradigm Blob," referring of course that that monstrous universe I escaped from. When you have Sex, Drugs and Fame, when you've escaped the bondage of centrist serfdom, you don't need land, bread or peace. Or rather, you have land, bread and peace. Still, Ours is a totally unfinished revolution. It will never be safe so long as that Paradigm Blob in America and its agents--those well-meaning, pious, cruel expatriates--are pushed back far enough that they cannot threaten the superior counter-paradigm that Russia offers. Actually creating a rival superpower, a competing context--that's another task. The only real task that the eXile has. In time, we attracted more and more foreign press. We'd appeared in articles and news programs. We made appearances on Russian television, and attracted Russian journalists to write for our newspaper. All of this pulled us out of the margins and into the world of legitimacy. Something had happened. The Beigeists' most powerful weapon--ignoring and silencing the opposition--was no longer effective. The two-front approach we led had earned us an officially recognized seat in the General Assembly. They were lumbering and clumsy and slow to act. When they finally retaliated, it only worked to our advantage, the way hatred and violence increases the power of the Devil. Kathy Lally of the Baltimore Sun argued that the eXile should be banned from a popular and highly influential Internet forum for Russia-watchers, the Johnson List. We retaliated by playing one of our most devastating practical jokes of all: we caught her agreeing to back a boycott of the eXile's sponsors, and considering acting as a witness in what our phone caller claimed was a criminal investigation into our alleged "hate crimes." We printed the conversations, and she hasn't been the same since. Drugs Are Fun JOURNALISTS aren't just professional liars, propagandists and pickpockets--they're also the lowest, most shameless careerists and ingrates on planet earth. The accumulation of drugs=despair articles in the fall of 1997 spoke more of a conspiracy among careerist hacks than anything remotely resembling the truth. What people forget in every article ever written about drugs is one simple, basic fact: PEOPLE TAKE DRUGS BECAUSE THEY'RE FUN. That's it. It's the most basic premise of all. There's no mystery to the drug thing. People drink water to quench their thirst; they have sex because it feels good; and they do drugs because they're fun. Is it really that difficult a concept to run by the reader? Is this obvious fact really so dangerous and censored that we can never utter it in the printed public? Even Hunter S. and William Burroughs couldn't state it that plainly: they elevated drugs to the mythical level, keeping mum on the single most obvious, dangerous fact. So I'll repeat: PEOPLE DO DRUGS BECAUSE THEY'RE FUN. It's no different from alcohol or roller coasters, except that drugs are A LOT BETTER. If everyone would admit that people do drugs because they're fun, then suddenly, the whole 30-year war on drugs thing would seem savage and bizarre: the war on fun. Which is exactly what it is. Drugs are also incredibly practical. They can help you get through rough times. They can numb you to horrible circumstances. They can improve your social skills. Or they can increase your work efficiency. When I was stuck doing three issues back-to-back, all alone, it was the speed that stepped in as deputy editor, copy editor, ideas-man and gopher. I went days without sleeping, just railing out one strelka, or arrow, after another. True, each issue was worse than the previous one. The last Taibbi-less issue was almost a complete editorial disaster. Readers were beginning to complain about the decline in quality. It could have been worse, though. There could have been no newspaper at all, with me hanging from the ceiling, a scrawled note pinned to my body: "I didn't have what it takes. Go on without me. M" The Beige Bogeyman IT WAS IN THE summer of 1998, as Russia's financial crisis spun totally out of control, that the truly formidable Beigeist Michael McFaul opened up a new front against us, arguing that we should be banned from the same Internet list because we allegedly supported violence against women. The Stanford associate professor, leading Carnegie Endowment analyst, Hoover Institute tool (note the squeaky Clinton-like synthesis of liberal Carnegie and conservative Hoover creds), and the Clinton Administration's most relentless academic propagandist in favor of its near-genocidal reformophilia. As McFaul's SimCity global-village-paradigm crumbled around him in a reality of corruption, cynicism and destruction, he decided that taking on voices of opposition was more important to The Cause than writing truthfully about Russia. McFaul pressured David Johnson, who ran the Internet list, to ban the eXile, based on the now-infamous "rape" article by Johnny Chen. He argued that a publication that glorifies rape in its pages should not be allowed a forum on a "serious" academic list, even if the editor of that list, David Johnson, only reprinted relevant and serious political articles from our newspaper. McFaul argued that by posting our "serious" pieces, Johnson was "tacitly condoning rape and violence against women." In another time, we would have lost without a fight. McFaul expected it to end that way: his ugly confidence showed through in his postings to the list. In the world he came from, you won debates by flashing your credentials, and that was that. A show-trial display of debate might be allowed--the kind of false, cringing, shamefully polite debate that his people conduct. In his Stanford/Carnegie world, a pair of wounded tweaks like Taibbi and me would simply get zapped by 100 rectons of McFaul voodoo-rays, and that would be it. I was terrified and seething mad when he first tried to silence us. Night after night, McFaul and I squared off via email. It got nastier and nastier. I'd whiff out, pound the computer and curse in my oven-like box-sized apartment during those long July nights. I could imagine where McFaul was, on the other end of this Information Superhighway: either in his quiet office on the Stanford campus, in that quaint, nauseating ranch-setting in the rolling Peninsula foothills, where robins and bluebirds chirp in the oak trees outside of his open window ... Or if he wasn't on the Stanford campus, playing god to the sons and daughters of America's oligarchy, then he was reading some comforting Daniel Boorstein book in the study of his two-story Palo Alto home, oblivious to the low background hum of lawnmowers and weedeaters, as a crew of illegals from Guatemala manicure his front yard. I can picture it perfectly because I was reared in Saratoga, about 20 miles south of and 20 degrees hotter than the bay-cooled Palo Alto. McFaul's golden retriever, inevitably named Pasha or Sasha, gnaws on an expensive handmade Earth Toy underneath the mahogany wood desk. His Volvos--both of them--are safely parked in his neatly organized garage, oil trays beneath the chassis. A police patrol car slows before his home to make sure that the Guatemalan gardeners are staying clear of the doors and windows to the McFaul manor. The Guatemalans obligingly cower before the cop. Satisfied, the patrol car moves on to check up on the next two-story beyond the hedges. Mrs. McFaul, who chairs a domestic violence support foundation, returns home late. Over a skinless chicken dinner, she talks about her good fight, while Dr. McFaul, an agitated vein bulging in his forehead, recounts his battle against the eXile, the very incarnation of the McFaul-ian bogeyman. Taibbi and I kept quiet at first. Johnson queried his subscribers as to whether or not McFaul's ban should be enforced. The response was overwhelming: tens of letters representing local bureau chiefs, Russian journalists and various academics, as well as others, came to our aid. We'd become too famous to fuck with. Banning us would mean violating another one of those sacred Beigeist tenets: Thou Shalt Not Censor. It was sweet. We piped in, renaming McFaul "McFalwell" and abusing him from every angle possible. Eventually, he sent an email saying, "Okay, you win, I'm exhausted. I give up." Shortly after, his colleague at Stanford, Gordon Hahn, also of the Hoover Institute, started another email war with Taibbi and tried to have us banned. Within a week, he also surrendered and even apologized. No Return EVEN IF my sex and drugs supplies were slashed to pre-Revolutionary levels--which, in the last few months, has happened--I wouldn't leave Russia. Those are the perks, well-deserved perks, but no longer essential perks. They aren't the reason I came. The most important thing is protecting Russia from going the way of Prague. From becoming a domesticated, obedient member of the Global Village. This paradigm, this counter-universe, so fragile, must be preserved, if only because my very health depends on it. Russia is my home. I have never, not once since moving here, thought about returning to America. Or anywhere else. As this chapter is being written, the Yeltsin regime responsible for creating this horrible, bizarre and yet epic paradigm is cracking apart. I have no idea what will come next, but my instincts tell me that I'll have to be more careful if I want to stay, and avoid getting nailed to the side of a church. Can't have the Russians thinking I'm merely here to rape and pillage. Wouldn't be prudent--or safe. "Uh, guys ... heh-heh ... it was a joke, get it? Yeah?" No, the next people in power won't get it much at all. Anyway, the best thing is to aim our guns Westward only. If only to keep them off our property. [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the May 25-31, 2000 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 2000 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.

Bouncing the Czechs

Bouncing the Czechs

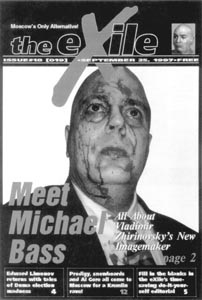

Xtra, Xtra: A candid snapshot of a bloodied Michael Bass--American Jew, petty con artist and aide to anti-Semitic demagogue Vladimir Zhirinovsky--provoked a threatening and barely literate response, which the eXile published verbatim.

Xtra, Xtra: A candid snapshot of a bloodied Michael Bass--American Jew, petty con artist and aide to anti-Semitic demagogue Vladimir Zhirinovsky--provoked a threatening and barely literate response, which the eXile published verbatim.