![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Where have you gone, Jack Allen?

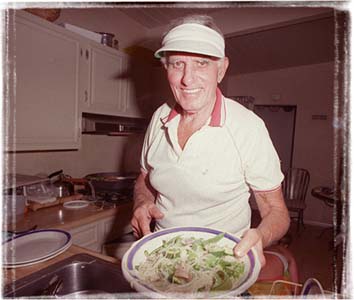

Dan Pulcrano Jack Allen in 1987. By Dan Pulcrano LONG BEFORE ALICE WATERS was celebrated for inventing California cuisine, Jack Allen combed local markets for sweet figs, raspberries and Comice pears, and the docks for fresh Petrale. Allen called San Jose in those days a "Roller Derby town," for its restaurants specializing in chicken fried steak, roast beef and "the fish of the month." He cared little for French culinary pretension, terming their bilingual menus "redundant," and pointing out that sauces evolved to mask the smell of old meat cellared by noblemen with a penchant for overhunting. He had equally little patience for contemporary culinary fads. "The Italians have been cooking nouvelle cuisine for centuries," Allen noted. Nonetheless, he acknowledged, "some of the worst cooks in this country are Italian." Many wharf restaurants "would close up if they lost their French fryers." Born to the Sicilian-American family that founded the Contadina tomato paste cannery, Allen was a man of prolific opinions. He relentlessly wrote letters to politicians and editors to rail against the insanity of nuclear weaponry or complain about the man he called "that idiot in the White House," Ronald Reagan. Equally passionate about overdevelopment and sprawl, Allen penned columns that mourned the destruction of the idyllic Santa Clara Valley of his youth, comparing his creekside jaunts between San Jose and Alviso to "a trip down Mark Twain's Mississippi." "We should have a Requiem service and bow our heads, paying homage to the bizarre fact that perhaps the best soil in the world lies buried under millions of tons of concrete and macadam that acts as the foundation of our far-flung and sprawling residential areas, regional shopping centers, technological plants and heavy industry that clutters up the valley."

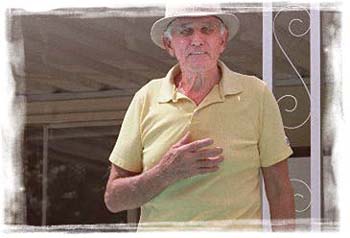

Jack Allen serves a plate of cappellini primavera at his Palm Springs home. I ENJOYED HANGING OUT with Jack when I was in my 20s. He was a guy with style who knew how to live, and the half-century age difference between us seemed to dissolve in his eternally youthful ways and his stories from America's lost past. When I'd see his Jag parked outside Paolo's, fedoras lined up under its rear window, it was a signal to take a break from the rat race and savor things that really matter: friends, good food and stories about gangsters , baseball heroes and movie stars in the '30s and '40s. At Paolo's, the restaurant he founded, he loved to talk about how he conned a New York restaurateur out of a prized cheesecake recipe for his pal Joe DiMaggio. The bartender would mouth the words over his shoulder as Jack delivered the punchline word for word, as he had done several hundred times before. Jack would invite me down to Palm Springs, and one time I took him up on the offer. I wasn't really surprised when I saw the 74-year-old sunning himself by the pool amidst seven bikini-wearing women in their early 20s, including three nurses from Sweden. "Jack, where did you find them?" I asked. "In the supermarket," he replied. "I invited them over for pasta." And three days later, they were still floating around on air mattresses. In between sautéing peas, zucchini and mushrooms for the cappellini, he would toss a cast iron chair in the pool, or jump in wearing golf shoes and a fedora. "Shit, that hat cost me $120," he'd say, then laugh. During one of the supermarket runs, Jack started splitting peaches in half in the fruit section, until it attracted the attention of the produce manager. "You call these things peaches!" he lectured the poor soul. "They're dry inside. Peaches are supposed to have juice!" Jack cussed like a sailor and didn't hesitate to take anyone to task for delivering a shoddy product or service. Anyone who spent any time with him, though, came to know he had a heart of gold. He raised money for everything from diabetes to psoriasis, fed the homeless, took young people under his wing and paid for their educations. Employees stayed with him for decades. And celebrities sought out his acquaintance because he refused to flatter them. Age finally caught up with Jack, and he spent his final years in bed at the home of his daughter, Carolyn. Although his sharp mind was bent by that cruel and bizarre disease named after Dr. Alzheimer, he must have gotten word that his friend Joe DiMaggio was waiting at a corner table on the top floor. He died Monday at the age of 87. And just as DiMaggio's passing marked the end of an era for America, Jack Allen's departure closes the book on a period in San Jose's history [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the May 27-June 2, 1999 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 1999 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.