![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)

![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Music Index | Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

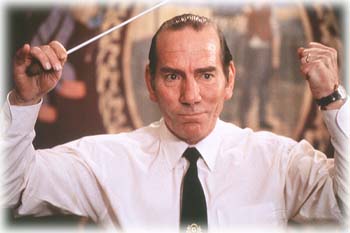

Unusual Suspect

Pete Postlethwaite talks about Brassed Off, Keyser Soze and William Shakespeare

The matchless gravity of actor Pete Postlethwaite was first noted by those who saw him in Terence Davies' 1988 film Distant Voices, Still Lives. The shadowy British memory-piece was about post-WWII life in Liverpool and the successful escape from it--in movies, in drink and in popular song. Postlethwaite played a tyrant of a father, based on Davies own dad, and displayed a rage and sorrow seemingly too big for one man's body to contain.

It wasn't Postlethwaite's first movie (he had a walk-on 20 years ago in Ridley Scott's The Duelist), but over the years since Distant Voices, Still Lives, Postlethwaite-spotting has become a pastime. Some recent sightings: stealing the show as the only one in the cast who knew what iambic pentameter was in Baz Luhrmann's William Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet [as Father Lawrence]; turning up, sleek as an viper, as the lawyer Kobayashi in The Usual Suspects.

Shaven-headed and earringed, like Mr. Clean on a bottle, Postlethwaite plays a great white dinosaur hunter in The Lost World: Jurassic Park, before leaving the picture midway with the parting line, "I've walked in the company of death long enough." (Certainly, he's walked in the company of dialogue like that long enough, as have we all.) But the film closest to his interest right now is the little comedy/drama Brassed Off (translated from the British, "Pissed Off").

Postlethwaite plays Danny, the captain of a sinking ship. It's the small town of Grimley in Yorkshire 1992; the right-wing British government has plans to close the coal mine. The colliery's century-old brass band, which Danny currently leads, is thus also doomed, but the group gets a shot in the arm with the arrival of Gloria (Tara Fitzgerald).

Ewan McGregor (Trainspotting) and the ridiculously pretty Fitzgerald provide the love interest. The story of the labor struggle is blended with the band's shot at a national band competition. It's an evocative, funny film, but it could have used more light and less heat in the finish. Director Mark Herman underscores the obvious pathos of the story. Postlethwaite, however, acquits himself with ease throughout. When the movie addresses you as if you were at a public meeting at the end, his quiet integrity almost carries off the closing speech.

I interviewed Postlethwaite at a hotel near Union Square in San Francisco. He had been here before, during his small role as the Old Man who gives James Henry Trotter the magic oddities in Henry Selleck's James and the Giant Peach. "That's when I fell in love with San Francisco," he says, "It's very vibrant, very full of life.")

Metro: Where are you from?

Postlethwaite: Just outside of Liverpool, in Lancashire, a place called Warrington. I'm very much rooted there. We're actually living in Shropshire now, a place about 70 miles south of Lancashire. Very different, very beautiful, wild country, pretty much unexploited, pretty much untouched. People say to me, don't you live in L.A. No, why not? I say, one day, come to Shropshire and see where I live, and then tell me to live in L.A.

Metro: You have been working a lot lately.

Postlethwaite: Like a gerbil on a treadmill--and I know every tread by heart. Well, not quite. I keep saying I won't do anything for a while, and then somebody throws a script at me. I am trying to regulate my life a bit, so that I can slow down a wee bit.

The films that I've done, I've done because they were beautifully crafted, beautifully written scripts, with directors who had fantastic visions of what they've wanted to do. Not one of them do I think, 'I'm sorry I did that'--not one. That's luck, really, that's luck as much as anything.

Metro: There's a certain limitation on British actors in American films.

Postlethwaite: Yeah, but then again, you get to do something like Romeo and Juliet, which was the first time I'd done Shakespeare on film.

Metro: You'd done Shakespeare before, though.

Postlethwaite: Oh, yeah, I was in the Royal Shakespeare company for five years. Anyway, I was doing an American accent, and not one person mentioned it all in the reviews. That's great. The world of international film is global, we have to get rid of these categories those barriers and divisions the better.

Metro: I didn't notice the American accent, but I did mention that you had the phrasing right.

Postlethwaite: If you try to go against the rhythm of those lines, they'll eventually win. You have to go with them, but not in a sing-songy way. If you go with them, they'll help you pull you along--you can do 10 lines without taking a breath. The more you do it ,the better you get. He's one of my favorite writers; he does write a good yarn. And I think Baz Luhrmann did a terrific job.

Metro: I've noticed that British film critics always seem to feel "we've had Shakespeare"--what they don't realize is that you don't have much first-rate Shakespeare in the U.S. and the rest of the world.

Postlethwaite: They didn't take umbrage at the new Romeo and Juliet; even theorists thought it captured the zest of youth. That's why the story is alive today. And it was definitive--it will be another 10 or 15 years before anyone does another film of Romeo and Juliet, just like there hadn't been one since the Zeffirelli version.

In the Beginning

Metro: Distant Voices, Still Lives wasn't your first film, was it?

Postlethwaite: It was the first film I did a major role in. I can't remember what I've done. Someone dug out on the Internet--The Duelist, but all I did there was shave Robert Stephens. I can't remember the chronology, but I was in The Dressmaker and A Private Function. But Distant Voices, Still Lives is the one that people appreciated. I don't know how well it went into the public marketplace. It was In the Name of the Father that spread the name of Postlethwaite across the globe.

Metro: What was Terence Davies' directorial style like?

Postlethwaite: Extraordinary. He had a very, very precise vision and aural perception of what he'd wanted, of what piece of music was going to accompany a scene, how long a shot would take. Very mathematical: In a nutshell, he'd say a scene will take place at 13 1/2 seconds.

Metro: That precise?

Postlethwaite: It was quite strange for an actor who was used to improvising. Strangely, I enjoyed the discipline and embraced it. It was a different discipline--different from working with somebody like Jim Sheridan on In the Name of the Father. At one point, Sheridan threw the script into the Liffey [the river that runs through Dublin] and said, "Sod the writing--we'll see if it looks good."

Metro: When you received the script of The Usual Suspects, could you tell you had something really different?

Postlethwaite: I read it, and I didn't understand it the first time, but it didn't matter. You knew it had sinew, it had depth, it had wit. I met Brian Singer, the director, over lunch. I told him the script was fantastic; he asked me, "What do you want?" "I said, "Any part." He said, "Why not? They're all Keyser Soze."

Metro: So, are you Keyser Soze?

Postlethwaite: Who knows? Nobody knows. That's what's good about The Usual Suspects. The audience is a lot more intelligent than we're led to believe. They love to be challenged. I don't think people really want visual chewing gum. I think they want something that does everything to them. It's a challenging film; critics said you had to go twice. What producer in the world wouldn't love that?

And the Band Plays On

Metro: Your new film Brassed Off is set in Grimley. There's not town called Grimley, is there?

Postlethwaite: There is a town called Grimesthorpe; that's the place where the story happened in real life.

Metro: And you'd say you came from the same class as the miners?

Postlethwaite: Very much the same class. In Lancashire, there are more steel mills. There are coal pits in Lancashire, but more of them in Yorkshire, in those rolling hills there. Culturally, classwise, I'm from the same people.

Metro: What was the economic explanation the Tories made for the closings of the Yorkshire coal mines--was it a "bottom line" argument?

Postlethwaite: They tried to say that it was an economic argument, but when that didn't work, they argued that the way forward would be nuclear power. There was still lots of coal, and now the mines are closed and we're importing cheap coal from Poland. The reason why the Tories gunned the miners in the pit was that they were politically active. The smashed them so they closed down the pits. The conservatives made war on the unions, and won, in fact.

Metro: What's the effect now?

Postlethwaite: Apocalyptic. The pit was not only closed down but destroyed, razed. They covered the pits up with concrete, burying a quarter of a million pounds worth of equipment.

Metro: What was the point of that? Plowing the land with salt?

Postlethwaite: That was vindictiveness, because Grimesthorpe had one of the strongest unions. She [Margaret Thatcher] made an example out of them, that's what she did. Out of the goodness of her bitter, twisted little mind. Lovely lady.

Metro: How long were you up in the north of England making Brassed Off?

Postlethwaite: The shoot itself was eight to nine weeks; we went up, me and Steve Tompkinson, who plays my son, up two weeks earlier. We just drove around, and said, "hello," and people said, "hello" back; after that, we were accepted. Then we started going to some of the miners' pubs, listening to their stories.

Metro: Were the local people touchy when you first arrived?

Postlethwaite: They were a little bit so, because about a year or two years before, there had been a film crew come to do a documentary about them and supposedly the crew was giving the kids �5 notes to throw rocks at the windows. After a few weeks, they saw that what we were doing wasn't like that. We had a great responsibility. We were making a film about a community that's been ravaged already; you don't want to go in again and ravage them with a poor, shoddy film.

In the same way, when the local people found out that Ewan McGregor could actually play the cornet and that Tara Fitzgerald could play the fluegelhorn and that I could actually sort of keep them in time with the wagging stick--then the community could tell we weren't there to take advantage of them again.

Metro: Did you have any musical training before you went into this film?

Postlethwaite: No musical training whatsoever. I can't read music. The soundtrack was prerecorded at Abbey Road, and I just listened to the soundtrack over and over again. You have to play it loud. It drove the family mad. They said, "It's either you or that brass band--one of you has got to go."

Metro: The editing on the finale of the performance of the William Tell Overture was especially rousing.

Postlethwaite: The camera was on a crane and on a track, to track down and crane in. Quite rightly, they used the most extraordinary technique to do the most extraordinary piece of music. The music is like a character; it builds and builds. They really went to town with that sequence--a really excellent piece of filmmaking.

Metro: Which film do you think it was that Steven Spielberg saw you in that led him to cast you in The Lost World?

Postlethwaite: In the Name of the Father, which was in opposition to him at the Oscars the year of Schindler's List. It was his bar mitzvah that year. And quite rightly, too, I think. If it had been any other year, In the Name of the Father would have won more. But there you are, that's the luck of the draw.

Metro: And you're in Spielberg's next film, about the slave-ship mutiny in the 1850s?

Postlethwaite: I play the District Attorney William S. Haliberd, who prosecutes the case. [This means he's the villain.] A Yankee, with a New England accent.

Metro: And aren't you due for some British stage work in the near future?

Postlethwaite: I'm sworn to secrecy. Supposedly you lose the impetus if you talk too early, but I should be on stage in London by this November.

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

This page was designed and created by the Boulevards team.

Web exclusive to the May 29-June 4, 1997 issue of Metro

Copyright © 1997 Metro Publishing, Inc.