![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

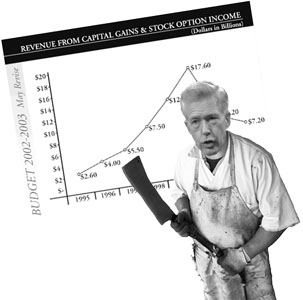

They Feel Our Pain As the state's budget crisis worsens, county leaders do their best to dodge the bullets headed their way, but it's inevitable some critical programs will be hit By Jeff Kearns THIS YEAR'S FISCAL climate has created a kind of economic perfect storm that has the state government looking at the steepest one-year revenue decline anyone's ever seen. Part of the blame falls on what the state spent to bail itself out of its energy crisis. But even outside California, the dual assault of the nationwide recession and terrorist attacks have the feds and almost every state in the union operating in the red. Silicon Valley played a disproportion-ately large role in this year's revenue fiasco. During the years the state enjoyed unprecedented surpluses, the boom in Silicon Valley was responsible for the landslide of money pouring into state accounts. When the economy cooled off, so did the valley's economic engine. From 2000 to 2002, state revenue from capital gains and stock-option income fell from $17.6 billion to $7.2 billion. And since the county gets about two-thirds of its budget from state and federal sources, local officials are in a panic about what's happening in Sacramento and Washington, even as revenues have dropped significantly in the county, too. Sales and property taxes plummeted, and county number crunchers predict that the growth in property taxes will fall to half of what it was last year--from 14 percent growth to 7 percent. County Assessor Larry Stone says property values are down 15 percent from last year, a $3.7 billion drop. However, as predictions worsened last year, and local governments saw the shortfall headed their way, the governor pledged in January not to raid the local government cookie jar. But that was January, when the shortfall was a measly $12.5 billion. Who knew the amount would double? In any case, when Davis released his revised budget in May, counties got a cold, hard look at the $1 billion shortfall in all of its ugliness. It's not as bad as some had predicted, but it's still going to be tough on Santa Clara County, especially in the health and human services department, which means more people on the street and more people not being able to move beyond joblessness and welfare. JIM BEALL HAS LOST track of how many trips he's made to Sacramento during the past months. "I got back at midnight last night," says the weary Santa Clara County Supervisor, the day after Davis issued the revised version of his budget. Beall met with the governor's top budget aides and with board members from the California State Association of Counties. "Everyone says they're willing to work with us," the Beall says, trailing off in a way that leaves little doubt that he's skeptical. For counties, the revised budget proposal was a mixed bag, and their fortunes will almost certainly change once hearings begin. But everyone agrees, even in the best-case scenario, it's not going to be pretty. And the worst of it is that as lawmakers gear up for a budget battle that could stretch into fall, counties must face the prospect of approving their budgets in June. They will likely have to come back after the state budget is finalized and make a second round of cuts even more painful than the first. Santa Clara County is already $85 million short, but supervisors are resigned to the fact that they may have to come back in a few months and make more cuts--bringing the total up to $130 million, or more. To be fair, that $85 million represents just 4.5 percent of the county's $1.9 billion general fund, as opposed to the $23.6 billion, or 30 percent, that the state must cut from its $78.8 billion general fund, but it's still a deep cut for the county. County Supervisor Don Gage, who drove three hours each way to spend an hour and a half in Sacramento, thinks he got through to Speaker Herb Wesson. "Herb got the message that they just can't cut another $50 million. He seemed very sincere, and he came from an environment like ours. His people were there taking notes. But really, I think he got it. I don't know what'll come out of all this, but if they leave us with $50 million worth of hurts, we'll be in a world of hurt. If they nail us, the whole ship is going to sink." HISTORICALLY, Sacramento looks at local government the way Jesse James looked at trains--as an object of plunder," says Bob Brownstein, who served as chief of staff to former Supervisor Susie Wilson during some of the lean years of the 1980s and later worked for former San Jose Mayor Susan Hammer. "Ten years ago, they stole $3.5 billion, and counties have minimal independence, so when the state decides to take a chunk away it's very painful." In the early '80s, after Prop. 13, Brownstein recalls, "board members were in agony--with every option they'd have blood on their hands. County services have extraordinary impact. It's not median landscaping; it's dysfunctional people not getting clinic visits. The stakes are high." That's the scene counties wanted to avoid this year, as Sacramento stares into the deficit's gaping maw. Still traumatized by the budget crisis of a decade ago, local government officials like Beall and Gage from up and down the state began lobbying Sacramento on that issue last year, earning a pledge from Gov. Gray Davis that he would not close the budget gap by cutting the flow of money to cities and counties. The plea was especially important for counties, which get the biggest piece of their revenue pie from the state. And while not all of the county's cuts will be noticeable to most residents, some changes will have the potential to disrupt lives. "We're certainly in a crisis moment," says Amy Dean, head of the South Bay Labor Council. "What all this should point to is that we need to learn from our mistakes, extract some lessons from the early '90s and recognize the structural problems of the budget." Adds Dean: "The budget is an expression of our values as a community. And consequently, the kind of decisions we make--what we expand or contract--is based on those values." For Beall, some of the most painful cuts will be the ones that save money in the short term but come back to haunt the county later. And one of the most painful examples of that for Beall, a longtime proponent of mental health causes, is just that: mental health. On one of his trips to Sacramento, Beall took his case to the Assembly Health and Human Services Budget Subcommittee, highlighting his concerns that mental health and substance abuse costs will be shifted to counties by the governor's budget. "That may save them money, but in the end it ends up costing more. If you cut those programs, you end up putting more people in jail," Beall says. We're worried that this is going to wipe out the last five years of progress" by the county. Beall also testified against an Assembly bill that he said would cut funding for special education and other programs for kids with mental health problems. "It's so expensive when you deal with a kid like that, so prevention is really important because a lot of them can end up in the criminal justice system." Steven Levy, director of the Center for the Continuing Study of the California Economy, who recently made the case for tax hikes to offset the budget crisis, says budget cutting is not only painful, it pits constituencies against each other, resulting in a no-win situation. "Revenue cuts are so difficult to make, all people understand the damage these cuts will cause," he says. "We're all connected, and the connections of a world-class society extend to shared prosperity. We should protect everybody, because if we don't, we don't protect anybody." Adds Supervisor Pete McHugh, chair of the board's finance committee: "Mental health and public health are the last to be expanded and the first to be reduced." What's at stake? "The quality of life for people that live here," McHugh says. So while the Sacramento and American rivers will likely spill their banks with red ink this summer, the pain is just beginning for local governments. The so-called recession may be evaporating--or, again, it may not--but the effects of this year's mess will drag on for years as leaders at both the state and local levels deplete their reserves, defer pricey one-time expenses and borrow to make ends meet--all but assuring that the next one or two budget cycles could be even worse. Although specific cuts are still pending, following are some of the areas which legislators and insiders feel are most likely to feel the pain this budget year and how it will play out locally. Brace yourself--the long, hot summer in the Capitol will be a little hotter and lot longer than usual.

Loren Stein also contributed to this report.

Send a letter to the editor about this story via email . [ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

|

From the May 30-June 5, 2002 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.