Waiting for RU486

Doctors in San Jose are offering new drug treatments that allow women to choose alternatives to surgical abortion. But they aren't talking about the least painful alternative.

By Cecily Barnes

I FOUND OUT I was pregnant the day after my 23rd birthday. When the telltale pink lines appeared on the indicator window of my home pregnancy test kit, I saw my life pass in fast-forward. What about my career, my still-new relationship, my road trip? My boyfriend drove up soon after the discovery, and he was equally horrified. "I still sleep on a mattress on the floor," he said, almost choking.

It wasn't the right time in my life to have a baby; I was clear about that. What I wasn't clear about was what to do. I hated the thought of surgical abortion. A friend said she'd heard of a local clinic administering the still-banned abortion pill RU486. That Monday at work, I frantically searched the Internet for information. Although I couldn't find any clinics where the French abortion pill RU486 was offered, I discovered that an alternative to it, called methotrexate, was being tested at local Planned Parenthood clinics, one right here in San Jose. By day's end, I had made an appointment.

Heather Smith, an R.N. at the Planned Parenthood Clinic on The Alameda, knew the drill. As I sat with the super-sized paper towel across my lap, she calmly rattled off information about the new therapy undergoing human trials in San Jose. She'd been through this with dozens of women like me before. The process involved two pharmaceutical drugs, she explained--methotrexate and misoprostol. San Jose is one of the six places in California where the process is available.

It works like this: a pregnant woman is given a shot of methotrexate, traditionally used to treat cancer, which stops the cells in the uterus from dividing and growing. Five to seven days later, the patient takes suppository tablets of misoprostol, a drug used to treat stomach ulcers. That causes what Smith says will be like a heavy menstrual period. No risks associated with surgery, no walking through the protesters, no waiting the seven weeks required for surgical abortion.

It sounded too good to be true, and I wanted to know the drawbacks. The first, she told me, is time. Women must wait five to seven days between the two treatments, so the abortion process takes about a week, sometimes longer. Side effects of the misoprostol can include nausea and vomiting. In rare instances, women can hemorrhage.

And women must be very sure they want to end the pregnancy, Smith emphasized. If the pills don't work, as they don't in 15 to 20 percent of all cases, women must have a surgical abortion.

"Basically, there will be grave consequences to the fetus," Smith cautions. "That's why the counseling element is crucial."

I decide that waiting five days for a drug-induced miscarriage is preferable to the surgical alternative.

Smith injected me with a shot of methotrexate, and I went back to work.

For the next five days, I had some nausea, but life continued more or less normally, except for the anxiety. I had made the decision to end my pregnancy, but still felt pregnant. I counted the days, carrying the misoprostol tablets and painkillers with me in my purse. Because the bottles were so bulky, my wallet had to stay at home.

What I didn't know, however, was that a better alternative did exist. That just up the highway, in San Francisco and Oakland, RU486 is being tested on women who are fortunate enough to have heard about it. Although health professionals all agree that RU486 is a better method of medical abortion, methotrexate is being tested only because it is politically preferable. Right-to-life groups have successfully kept RU486 from most women in the U.S.

"There's no question in my mind that RU486 is a better drug. It's safer, faster and more efficient," says San Francisco ob-gyn Bernard Gore, the only doctor in California distributing RU486. "Methotrexate has theoretical risks to the kidneys and the liver, and where you have to wait one week to abort with the methotrexate, RU486 usually works within 48 hours."

Nevertheless, Gore says he considers methotrexate to be a viable option. It's just that RU486 is better.

I wished I had found Gore before taking the methotrexate. But not knowing RU486 was available anywhere, I thought I had no choice.

Drug Money

METHOTREXATE AND misoprostol were first tested on pregnant women in 1994, when Dr. Richard U. Hausknecht placed an ad in the New York Times for "nonsurgical pregnancy termination." Both drugs had already been used in the United States for years, but for the specific purpose of treating cancer, ulcers, psoriasis and arthritis. Under U.S. medical guidelines, doctors have the freedom to prescribe drugs for "off-label" uses at their discretion. So far, however, few have jumped at the chance to combine the drugs for abortion for fear of malpractice suits or political reprisals.

Anti-abortion groups are furious about the new medical abortion technique, which can't be tracked, protested or blocked because of the medications' other widespread uses.

"The problem with methotrexate is that it's already FDA approved for use as a chemotherapy drug," says Laura Echevarria, director of media relations for the National Right to Life Council. "We feel that it's dangerous and irresponsible to use a chemotherapy drug to induce abortion, and we don't feel that women should be treated as guinea pigs."

But even though the group can't protest a drug that's already approved, the NRLC is not giving up. "Our efforts so far have been educational," Echevarria says, "letting women know what the dangers are and that the dangers are very real. We don't know the long-term effects this drug will have on the reproductive system or on future children."

Physicians deny that such dangers exist. But anti-abortion groups consider the new technique no less horrific than surgical abortion. According to Echevarria, the technique should be outlawed because abortion is wrong. But pro-choice organizations say they will continue to administer methotrexate until RU486 is legal.

Meanwhile, 12 clinics across the nation--including Women's Choice in Oakland--administer RU486 in a small study sponsored by the Abortion Rights Mobilization Group. The availability of the drug ends there. (See related story.) Right-to-life organizations have successfully kept RU486, also known as mifepristone, out of the United States by threatening to boycott any drug company that agrees to manufacture it. And since RU486 costs so little, drug companies are even less willing to take on the political hostility, given that they're not going to make a lot of money.

"We're waiting for someone to make this drug who is not interested in making a lot of money, because frankly there's not a lot of money to be made," says ob-gyn Gore. "Maybe the tablet costs eight to nine dollars. No company is going to want to deal with the aggravation if they're not going to make money."

Although the drug has been used successfully by more than 200,000 women in Europe since 1988 and has been found "safe and effective" by the FDA, and despite the fact that it has a significantly higher success rate than methotrexate, drug manufacturers won't come anywhere near it. Currently, the Population Council is working to find a company who will face the right-to-life contingent and distribute the drug. If RU486 is approved, Planned Parenthood director Kara Anderson admits, the organization will likely drop its bid to get methotrexate abortions approved by the FDA.

By conducting a study of methotrexate, pro-choice organizations ensure that a medical abortion option is available to women despite the politics. The study is still under way, and the final results will likely be presented to the FDA for the "safe and effective" stamp of approval in one to two years.

San Francisco physician distributes RU486 in the face of politically inspired ban.

Home Remedy

EGGO WAFFLES, instant oatmeal, a two-gallon jug of water, chamomile tea and an arsenal of maxi pads clutter the kitchen counter at my boyfriend's house Monday evening. At my request, he has even cleaned his room. Next to his bed lie copies of the New Yorker, Harper's, a community college summer schedule and four videos. I shower and put on sweat pants and a T-shirt my roommate loaned me for the occasion that says, "I'm not fat, I'm pregnant."

With U2's The Joshua Tree playing in the background, I brace myself for pain and insert the suppositories. It's 7pm.

Six hours, two movies and three waffles later, nothing has happened and I fall asleep. When I wake up in the morning, little has changed--no cramping and just the smallest amount of bleeding. I call the clinic and talk to Heather Smith. As the form said, she explains, only 50 percent of women respond to the first set of suppositories. Now I should wait until night and use the second set.

The next day I still feel no progress, and at 5pm I impatiently use the next set of pills. My boyfriend and I drive to Circuit City to look for a new stereo.

Twenty-four more hours pass, and still nothing. Back at work the next day, I call Smith, who agrees that I have probably fallen into the 15 to 20 percent minority for whom the treatment doesn't work. She schedules me for a surgical abortion that Saturday. The treatment had failed.

At this point, I wanted nothing more than to have my pregnancy ended immediately. Smith suggested that I wait another week and see if the cramping and miscarriage occurred on its own. No way. Everything was taking too long. Too many phone calls to the clinic and days of work missed. I wanted it to be over with. Suddenly the quickness and certainty of a surgical abortion sounded good. The clinic fit me in that weekend.

Saturday is abortion day at the San Jose Planned Parenthood Clinic. Smith and the other nurses purposely show up early and in street clothes to avoid harassment. Clinic doctors have been known to cut through parking lots and hop a fence to avoid protesters.

We arrive at 9am. Clinic escorts in blue aprons lazily eat donuts, waiting for the usual protesters to show. Since she started nine months ago, the 39-year-old Smith has administered medical abortions to 56 women.

"I feel really good about medical abortion because you can terminate so early," she says. "And luckily, there are, like, 20 Heather Smiths in the phone book, so the protesters will have a tough time tracking me down."

All told, I was there about three hours. After a preliminary exam and small dose of valium, I was back on the table. The procedure took three frightening, loud minutes. As soon as the noisy machine shut off, I took a deep breath. My boyfriend passed out. He was ushered into an exam room, and I was taken into recovery, where four other young women lay on beds, having just come through the same procedure.

I thought about striking up a conversation with the girl next to me but lacked the energy. A nurse about my age with long blonde hair stroked my head and asked me if I felt OK. I nodded. A half-hour later, nurses helped me dress and led me to the room where my boyfriend waited, drinking Kool-Aid and eating saltines to help his blood sugar. On our exit, four protesters stood in a semicircle on the sidewalk, leaning on their signs. They didn't even break their conversation to look up at us. My boyfriend and I shared an uncomfortable little laugh. The protesters were tired, I realized, and we were, too.

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

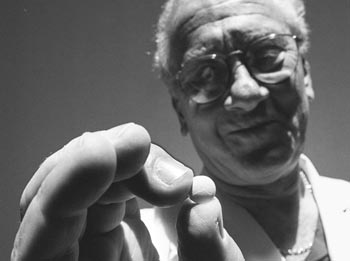

Christopher Gardner![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

From the June 4-10, 1998 issue of Metro.

![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)