![[Metroactive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

Rand Scheme of Things

The movie 'Spider-Man' nimbly sidesteps the cranky objectivism of co-creator Steve Ditko

By Richard von Busack

THERE IS A philosophical debate going on in Spider-Man that no one has addressed much in the reviews. Some critics have argued that the film resonates with a mass audience because of post-9/11 longings for a hero. That longing is stressed in the TV ads, in which a terrible sub-Journey anthem bays away as Spider-Man wraps himself around a flagpole.

Steven Winn of the San Francisco Chronicle wrote, "It's hard to watch Spider-Man's high-flying stunts ... and not register the vulnerability of those mighty Manhattan towers." Fair enough, and the New York locations function like a little vacation in themselves.

What's more interesting is the question of Spider-Man putting duty ahead of his own desire for riches and happiness, a choice that goes back to the origin story in the first issues of The Amazing Spider-Man. The incidents of the comic-book story are all there in the movie, with special attention given to doomed Uncle Ben, who tells his surrogate son that "with great power come great responsibilities."

This origin story was co-written by cartoonist Steve Ditko, and you wonder what he'd think of Uncle Ben's admonition today. Ditko, Spider-Man's reclusive co-creator, has been called the "J.D. Salinger of comics." The Los Angeles Times' Jordan Raphael recently profiled Ditko, who, as usual, refused to talk to the media. Ditko, a Pennsylvania-born cartoonist, illustrated and co-wrote 38 issues of The Amazing Spider-Man. In 1966, he quit the book, walking out on Stan Lee, the better-known writer and editor of Marvel Comics.

Recent communiqués from Ditko--as Raphael notes--show his current obsession with the mediocre masses dragging down the heroes of our world. "According to friends and former collaborators," Raphael writes, "Ditko's life has been heavily influenced by objectivism, the philosophy of rational thought and individual free will sketched out in Ayn Rand's novels The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged.

"Ditko sees the world in stark black and white, with no grays. As such, he does not compromise on issues that contradict his artistic or ethical sensibilities. In one incident, he stopped doing a series and furiously chastised the publisher because of a slight color error on the cover of the first issue."

One can only guess what Ditko would think of the way the movie goes against Rand's ideals. Willem Dafoe's Green Goblin delivers a speech to Spider-Man that goes something like, "There are 8 million people out there, and their purpose is to hold people like us up." But faced with a choice between surrogate fathers--Dafoe's wealthy Norman Osborn and humble Uncle Ben--Parker makes the choice that helps the most people.

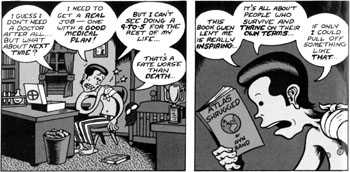

Comic-book artist Peter Bagge's satirical version of the debate between power and responsibility appears in Marvel Comics' The Megalomanical Spider-Man No. 1 ($2.99). This comic book, dedicated to Ditko, gratifies on several levels. While being about Spidey, it's still completely a Bagge comic book. Here is the familiar Tao of Bagge--the bulging eyes and the gesticulating crescent-shaped arms, the bad attitude and the defeatism all beloved by readers of the late, lamented Hate Comics.

In Bagge's satire, Spider-Man is depressed by one too many battles with costumed maniacs. ("Why do I subject myself to this? This is the police's job!") He gets his gloves on a copy of Atlas Shrugged and is inspired to go private. Founding Spider-Man Co., he builds a skyscraper and puts "that old bag" Aunt May into a retirement home. For laughs, he hires his old nemesis J. Jonah Jameson as his coffee-boy.

Bagge, lifelong comic fan that he is, colors his satire with some famous gossip about Marvel's golden age. Supposedly, at the height of the Marvel empire, Lee ordered his staff to refer to him as "Your excellency." Parker does this, too.

The selfish Parker gets his just deserts. After the heroically self-sacrificing, but completely accidental, "death" of Spider-Man, Parker (who survives) holes up as a writer in a Queens slum. In Bagge's final scene, Parker tells a reporter that his own misreading of Rand lead him into trouble. The reporter dismisses Parker as a kook. Still, Parker, this once-split character--now no longer an objectivist fanatic--finds contentment at last.

Rand's idea that there is a conspiracy of the mediocre against geniuses--the confederacy of dunces Jonathan Swift wrote about--is seductive to the oppressed few. But as an idea, it's too narrow for anything but satire.

The film of Spider-Man satirizes quite a few of our expectations. Still, there's a level of seriousness in it about the duties we have to each other. That's one of the many reasons why it's such an easy film to recommend: not just for the acting, which is roundly good, and not just for director Sam Raimi's enviable talent for slapstick (I loved the instant of the mutant spider pausing, as if savoring the moment, before he gives Parker's hand the fateful bite). Comedy aside, Spider-Man makes responsibility look romantic, even invigorating. The film is about a man free in the air who is yet always aware of what's going on down on the ground.

[ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.

![]()

In The Bagge: Peter Parker overdoses on philosophy in Peter Bagge's 'Spider-Man' satire.

Send a letter to the editor about this story

.

From the June 6-12, 2002 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.