![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

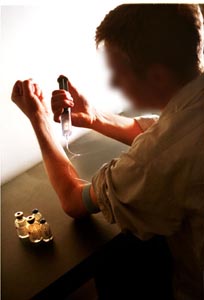

Drugs Not Shrugs: New drugs for the treatment of HIV can cost up to $170,000 per year. In the case of Marc, who acquired his HIV through plasma taken for his hemophilia, most of it is covered by insurance. The photographs have been modified to protect Marc's identity.

Drugs Not Shrugs: New drugs for the treatment of HIV can cost up to $170,000 per year. In the case of Marc, who acquired his HIV through plasma taken for his hemophilia, most of it is covered by insurance. The photographs have been modified to protect Marc's identity.

Photograph by George Sakkestad

Straight With HIV In today's dating scene, explanations, combination-therapy cocktails and supersafe sex are just a 'slice in the complicated life' of an HIV-infected man By Dara Colwell MARC IS TAPPING AWAY on his laptop computer, bent over its tiny keys like a mischievous child. He's emailing a woman he took out earlier in the week, an electronic flirtation that materialized but immediately became more platonic than romantic. "I've told everyone my date can drink and play shuffleboard," he types, laughing out loud. "I think we should retire to Florida together." Then he turns to me quickly, his job skills as a publicist coming to the surface: "Hey, don't write that!" but I make no promises. Marc's prone to putting his spin on everything, telling me how and even what to write. But what Marc will allow me to write is that there's a cardboard box stuck in the corner of his shallow closet. A box full of orange butterfly needles, a 30 cc plastic disposable syringe and enough foil-wrapped packages of rubbing alcohol to stock a nurses station. What he can't keep in the box goes in the refrigerator--a few thousand dollars' worth of concentrated plasma derivative, stocked next to aging condiments and bottles of amber ale. Marc is a hemophiliac and years of sticking needles in his arm and medicating chronic pain have made him flippant on the subject. But not today. "Talking about it sounds too hellish," he says. "I spend so much of the day being normal." He starts shying away from the subject, admitting to a kind of positive denial, and shrugs off my deeper questions. That's because, like half of the hemophiliacs in the United States, Marc is HIV positive. While the media has focused on women and children with AIDS, junkies, African Americans and Latinos, as a subpopulation, hemophiliacs are rarely in the picture. They only represent 1 percent of all AIDS deaths in America, yet more than 50 percent of their population is infected. And they were most likely infected before 1982, the year the Center for Infectious Diseases discovered three hemophiliacs--one in Florida, one in Colorado and the other in Ohio--who had AIDS. Marc was diagnosed with HIV in 1985 at the age of 19. Now in his mid-30s, he's still living, thanks to multidrug combination therapy. And he is part of a wider trend. Since the early '90s, AIDS-related deaths have continued to drop, by 60 percent in California and 47 percent nationally in 1997, according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). But even this is tenuous as there's no guarantee how well or how long combination therapy will work. "This is really a story with no conclusions," Marc says. "It's just a slice of a complicated life." MARC IS ONE OF 20,000 hemophiliacs in the United States. Primarily affecting men, hemophilia causes prolonged bleeding because the body lacks one of the factors needed for normal blood clotting. Depending on the level of these factors in the blood, hemophilia can be mild, moderate or severe. Marc has moderate hemophilia, which means he's at risk for bleeding after surgery or trauma and his joints bleed and swell. Marc's hemophilia wasn't "discovered" right away because he was adopted. When his adoptive mother, Marie, pressed for details (Marc was only a week old), the doctor claimed he didn't know the birth family's history. "But I had my suspicions," his mom says today, referring to a memory of changing Marc's diapers after his circumcision. "There was blood everywhere." Over the next few months Marc continued to bruise easily; he had hip and knee problems; and one day, at around 7 months old, he started screaming and he didn't stop for days--his knee was bleeding internally but the doctor thought it was a spider bite. Finally, he was diagnosed with hemophilia. Looking at Marc's baby pictures, it's hard to believe this chubby, Campbell-soup baby with reddish-blond hair and mischievous blue eyes could be anything but healthy. But by the time he was 4 years old, Marc had been in and out of hospitals for nearly 30 painful transfusions. Before the plasma concentrate he now uses was developed, But Marc's hemophilia was never really "visible." Nor is it now, save for a slight limp and some stiffness in his joints from arthritis. A tall, blond man with a somewhat angular face, Marc looks boyishly young and energetic, like the kind of guy who runs on the track team. It's only when he gets up slowly and begins to walk with a slight awkward turn that his limp becomes noticeable. The limp is surprising because there's always a restlessness, a kind of active curiosity lurking in his eyes. But the limp almost inevitably leads to questions and the questions lead to difficult answers. Hemophilia. Then HIV. The limp is usually the trigger.

MARC WILL NEVER FORGET the day in 1985 when he found out he was HIV positive. He was a 19-year-old student at San Francisco State University, and had gone for his routine annual checkup at the regional hemophilia center in San Francisco. During the checkup, the doctor told Marc he needed to draw some blood. There was a growing concern that the plasma products on the market were contaminated with the virus that caused AIDS. (The term "HIV" wasn't used until 1986.) Just a few years earlier the term had been GRID--Gay Related Immune Deficiency--but the syndrome was renamed because it was becoming clear that it didn't just affect gay men. Because hemophilia is treated by using freeze-dried factor 8 and factor 9 plasma concentrates, it is made from large pools of donated blood. It takes (on average) 20,000 donors to make up one lot, or batch, of factor. Because hemophiliacs use a dozen or so lot numbers every year, they are exposed to the blood of more than 200,000 people. At the time, in the early 1980s, the so-called Big Four drug companies (Alpha Therapeutic, Armour, Bayer and Baxter Healthcare) who made up the billion-dollar plasma industry maintained there was no risk, even though they were collecting blood from untested donors. And even though it was known that three hemophiliacs, with no other risk factors, had come down with GRID symptoms in 1982. Furthermore, the Federal Drug Administration (FDA), which agreed with the drug companies that the risk to hemophiliacs wasn't clear, never required a product recall. The factor on the market had a shelf life of two years. This was the factor Marc was using. And stopping wasn't an option. TWO WEEKS AFTER HIS TEST, Marc was called in. "I knew it had to be bad news," he says. A nurse sat him down in a plain office with a desk and two chairs, pointed to his charts and calmly explained that he had been exposed. "What does this mean?" Marc remembers asking, over and over again. The question, he says, still applies today. They didn't know, the nurse answered. What complicated the situation for Marc was that his girlfriend had just gotten pregnant and had an abortion. Marc couldn't get it out of his head that what he had was a blood-borne disease, a disease that could be sexually transmitted. How, he asked himself, could his girlfriend not be positive? The thought devastated him. He wanted to tell her but she was in class all day. Marc stood on the 15th-floor balcony of his dorm at SFSU waiting for her to come home, growing more and more despondent, wondering if he should jump. His mind raced: He could have unwittingly killed his girlfriend already; he could die himself. He was only 19 with his whole life ahead of him, but his life, he thought, had just ended. With hemophilia, he had faced chronic illness his entire life, but it was treatable. Now he had something else, something no one really knew much about. At that point he simply concluded "future-tripping wasn't in my playbook. The future didn't exist." As it turned out, his girlfriend did not test positive for HIV. MARC CONTINUED TO DATE, having several girlfriends through the years. One of them was Julie, a physicist with scientific curiosity, who wanted to know everything about HIV. She sent away for reports from the CDC, abstracts on HIV transmission, gathered documents on medication and downloaded graphs, charts--whatever she could find on the Internet. After collecting information, she approached Marc about taking preventive antiretroviral medication. She had noticed that people who were HIV positive were fine for 10, maybe 15 years, then suddenly their immune system just collapsed. Marc had been positive almost 12 years. His T-cell, or red blood cell count (a common measure of immune health) was at about 400. Below 200 is critical, normal is anywhere from 500 to 1,100. His viral load (the level of HIV found in the blood, specifically the number of amplified particles found in a teaspoon of blood) was high, at about 20,000. Julie wanted him to take the medication but it was Marc's decision. Taking antiretroviral combination therapy, also referred to as a "cocktail" (although the acronym HAART--highly active antiretroviral therapy-- is gaining use because the term "cocktail" sounds light-hearted and misleading), may seem like an easy decision. But the medication requires patients to follow a complex regimen, taking multiple medications several times a day. Some must be taken with food, others without. Missing a dose can lead to an increased risk for developing drug-resistant strains of the virus. In other words, once someone has started down the path, he may have to stay on it the rest of his life. And there's no certainty how long that path is. Marc finally decided to do it. To celebrate the occasion, he held a "cocktail" party at a bar. Surrounded by several friends, he drank to life. Marc's life now revolves around Crixivan (a protease inhibitor for HIV), Combivir (the "cocktail" of AZT and DDI in one pill), Naprosyn (which treats his arthritis from hemophilia) and factor 9 (plasma derivative). The medication seems to be working. He's bouncing back, with his T-cell count up and his viral load down. Marc's largest complication now seems to be financial. The factor 9 alone costs nearly $150,000 a year, and the HIV treatment nearly $20,000. Because he's a hemophiliac, most of the costs are covered by the state's Genetically Handicapped Persons Program. The rest, by insurance. In November 1998, the Senate passed the Ricky Ray Hemophilia Relief Fund Act, which required a $100,000 settlement be paid to hemophiliacs who acquired HIV through tainted clotting factor between 1982 and 1987. Ricky Ray was a 15-year-old hemophiliac who died in 1992. The amount--$100,000-- seems enormous, but Marc has spent that sum annually for the past 20 years on his hemophilia alone. "We've made the plasma industry rich," he says, hinting at the nasty irony. As I was finishing this article, Marc called and left a message on my answering machine. In a way, it was a typical publicist move--checking up on a pitch, making sure the story got out right. But the news was great. "I've got a little anecdote for your story," he said. He had just got the results from a hospital test, the most accurate test to date. His viral load was completely undetectable. "Pretty cool," he said happily. "I'm dodging the bullet again." [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the June 15-21, 2000 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 2000 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.