![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Movies Index | Show Times | San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Just Do It Again

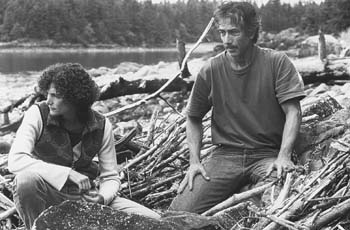

Next Time, We Go to Vegas: Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio and David Strathairn camp out in all the wrong ways in 'Limbo.' 'Limbo' and 'The General's Daughter' counsel that the second time's the charm when characters try to overcome emotional traumas THE QUICKEST way to restore an amnesiac's memory is a strong blow to the head, and the quickest way to cure a trauma is to force the sufferer to re-enact that trauma. I may not know much medicine, but what I've learned, I've learned in a movie theater. Two new films, John Sayles' Limbo and Simon West's The General's Daughter, both traffic in medical advice: the best way to get over a scarring experience is to go out and do it all over again. To be fair, both films demonstrate the disastrous consequences of Dramatic Re-enactments as therapy. The death of the title character in The General's Daughter comes after she restages a personal tragedy. In Limbo, David Strathairn plays Joe, a man who lost his crew in a boating accident. When he faces the sea for a rematch, he's overcome a second time. West tries to make his movie one of the most thoroughly distrusting views of the military since Ronald Reagan was elected president. Eventually, his nerve fails him. Sayles, being the more personal of the two directors, has the better imagery about greed corrupting the wilderness and the wilderness striking back. In his more than a dozen films, writer/director Sayles has studied communities from the Texas border (in Lone Star) to the grimier parts of New Jersey (City of Hope). But this communitarian quality jibes badly with what is actually a basic tale of survival in Limbo. The film is set in a fictional small town in Alaska. The canneries are shutting down; the place has almost completed the transformation from fishing town to a hamlet full of B&Bs. In a few well-chosen shots, Sayles could have established the atmosphere of this ailing town, with its most optimistic years behind it--if he weren't so literal-minded. He's telling, not showing, and he tells for about 40 minutes. One of Sayles' characters emerges to take over the story. Joe is a handyman who becomes involved with Donna, a flighty cocktail lounge singer (badly played by Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio), single-parenting a troubled daughter, Noelle (Vanessa Martinez). The budding relationship between Joe and Donna gives the man the emotional strength to go out to sea again. Enter the villain: Casey Siemaszko, playing Joe's estranged half-brother, Bobby, stinking to high heaven with unsavoriness. Bobby has drug dealers looking for him; they intercept the boat. Joe, Noelle and Donna escape with little more than their lives and the clothes they have on. Stranded on a remote Alaskan island, they wait for rescue. Sayles has the guts to leave his story with an open ending. The film literally closes in limbo. You could say that the early scenes of the decaying community are meant to underscore the isolation; you're not sure anyone will be looking out for the castaways. (But again, this could be suggested with compact storytelling and acting.) Haskell Wexler's photography in the second two-thirds is stunning; the blues and whites of icebergs and water look alive, as does the green dripping forest in which the three survivors hide, living on seaweed and mollusks. When Wexler is showing us how vast and cold Alaska is, we have the satisfaction of a story well told. But the acting is as rocky as the Alaska coast. Young as Martinez is, she outshines Mastrantonio. What should seem like an equal mix of resentments between mother and adolescent daughter instead makes Donna appear to be a stereotypical bad mom. Joe is supposed to have been a basketball player who blew out his knee, but isn't it hard to imagine Strathairn doing something joyous like playing basketball? This extremely morose actor was once a clown, strangely enough. Strathairn's teacher was Bill Ballantine, who wrote the best book about professional clowns, Circus World. I guess Strathairn must have been one of those sad clowns. JOHN TRAVOLTA, a more laid-back clown, perks up the dreadful The General's Daughter with his comedy. And yet the sorrow of a good community disintegrating suffuses this film as well. Stark raving dumb though it is, The General's Daughter is about the disillusioning of a macho military policeman who hero-worships a general. Travolta plays Paul Brenner, a CID investigator vested with the authority to arrest any officer in the Army. Madeleine Stowe plays Sarah, a rape investigator--Scully to his Mulder. The pair are assigned to investigate the rape and murder of the daughter of a revered general (played by James Cromwell), who has just retired and is about to get into politics. The general's daughter, Elisabeth (Leslie Stefanson), an Army captain, has been found murdered in the middle of an Army base. Was she snuffed because of her secret life as a dominatrix? Paul and Sarah find a cache of secret tapes of the dead girl roping and riding various slaves. The fishiest of all the red-herring suspects is the insinuating psychiatrist Col. Moore (James Woods), who is such a mad doctor that he even listens to classical music in a silk dressing gown. How could director West refuse to include a scene in which Moore explains how he helped Elisabeth devise a berserk re-enactment ritual to cure her of her emotional problems? Now, that would take some fast talking even by Woods' standards. As Gen. "Fighting Joe" Campbell, Cromwell checks in with a barely changed version of his Dudley Smith character from L.A. Confidential. Clarence Williams III also reports for duty as the general's aide; apparently, his office is a sauna, because he shows up as beaded with glycerin sweat as a rump roast in an advertisement. "There's three ways to do something," Williams' character intones. "The right way ... the wrong way ... and the Army way!" Director Simon West (Con Air) could have gone more than three different ways with this lurid who-done-it. More than one person I saw this film with suggested that the material ought to be sent up as satire, and sent up hard. But West leans on the story for tragedy. Certainly, The General's Daughter would be tragic if you could believe a minute of it. Travolta coasts. At one point he's bludgeoned by shovels, only to pop up in the next scene dabbing the back of his head daintily with a clean handkerchief, on which about a tablespoonful of blood can be seen. Having nothing believable to show, West tries to create a mood through algae-cam photography. I don't think there's a clean window in this picture. On the bright side, no one this side of the Bizarro planet will be able to use The General's Daughter as a recruiting tool. In telling a story that would scare any woman out of enlisting, West displays both a point of view and a provocative subject. But he undercuts them with the usual beauty shots of the machinery, the helicopters and planes. An aerial shot of the military academy West Point makes it look as exotic as the queen's palace in The Phantom Menace. West, however, compromises the frightfulness of his view by setting a subsequent scene in the greenhouses and vegetable gardens of the military academy. Even in this grim fortress, there are homely comforts, small good things--the scene is as laughable as everything else West puts on the screen, whether it's tony dankness or Freudian agony. JOHN SAYLES CLAIMS that when he makes his movies, setting comes first. The filmmaker had wanted to make a movie in Alaska, where he'd once worked in a fishery. He thought of making an adaptation of Conrad, but none of the novelist's works seemed right; still, Limbo includes some elements of Conrad's Lord Jim, that masterpiece about not being good enough for your ambitions. I wish that Sayles had added dimensions to Joe's character by showing how his shipwreck had weakened him, making him nose-blind to his half-brother's stink. I wish Joe hadn't been such a sturdy movie paragon. (The narrator of Lord Jim honors the titular hero, but he's ironic about his efforts to make up for one terrible mistake.) I also wish that The General's Daughter had been about a woman who had endured, somehow, what the Army had done to her. See, people who make the conservative choice to live in a small town or join the Army give up a lot of the pleasures of life because of their need for support; they enjoy the sense that people are constantly watching their backs. Real traumas have been healed in hospitals or talked out in group therapy or AA. When you think of how you got over personal troubles, usually you remember a lot of faces and not just one big ritual. Movies, however, require scenes of an individual cutting his own way in the world. The idea of fixing a problem with the help of an adventure is the simple excuse for a story, and, in a sense, not a real story. Only in the movies can you find expiation in two easy hours.

Limbo (R; 126 min.), written and directed by John Sayles, photographed by Haskell Wexler and starring David Strathairn and Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio. The General's Daughter (R: 115 min.), directed by Simon West, written by Chris Bertolini and William Goldman, based on the novel by Nelson Demille, photographed by Peter Menzies and starring John Travolta and Madeleine Stowe. [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the June 17-23, 1999 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 1999 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.