![[Metroactive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

![[Metroactive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Charles Dickens Superstar

By Jonelle Bonta

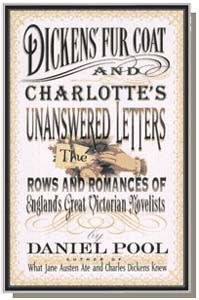

ANYONE WHO'S ever shed a tear over a Dickens novel or sighed over Heathcliff and Cathy--or just loves what Henry James called those "huge, floppy, 19th-century English novels"--will relish every page of Daniel Pool's Dickens' Fur Coat and Charlotte's Unanswered Letters. The book's subtitle is "The Rows and Romances of England's Great Victorian Novelists," but "A Secret History of the 19th-Century English Novel" would have been just as appropriate.

Pool is also the author of What Jane Austen Ate and Charles Dickens Knew, a secret history of Victorian life, from sex to money to tastes in furniture. Dickens' Fur Coat takes on the more substantial topic of the 19th-century publishing business and the birth of the popular audience.

In the dark days before Oprah, a book could cost more than a workingman's monthly wages, so reading was a rich-man's pastime. (In 1830, books sold for an average of 30 shillings--wages were about six shillings a week.) The standard was set by the massive three-volume "silver fork" novels, so named for their authors' obsession with the lifestyle of the upper class. Rather than buy, readers rented from circulating libraries, which dictated the format (and thus the market) for decades.

Like movies today, with their brand-name automobile and soft-drink plugs, publishing in early Victorian England was shamelessly commercial. Publishers advertised on buses; one actually hired shills to go to dinner parties and stir up conversation about his books. Novels were interspersed with commercials. (Thackeray parodied the trend in Punch: "The rich and luxurious may go to Dillow's or Gobiggin's, but we can get our rooms comfortably furnished at Timmonson's for £20.")

The silver-fork novels were so popular, Pool writes, that "even poets were trying to climb on the bandwagon. Elizabeth Barrett Browning decided in October 1844 that 'a true poetical novel--modern, and on the level of the manners of the day--might be as good a poem as any other, and much more popular besides.' " Given the opportunity, Mrs. Browning could well have been the Danielle Steel of her time.

In 1836, the novel was changed forever when a magazine publisher asked the 24-year-old Charles Dickens to write text for some comic prints. The serial novel, printed in cheap, monthly installments (as many as 20 in Dickens' case), created a huge, middle-class reading public.

Huge page about Charles Dickens.

The complete text of Charlotte Bronte's biography.

The Bronte Sisters archives.

Material about Elizabeth Barrett Browning.

DICKENS' POPULARITY paved the way for the second most important trend of 19th-century English literature, the emergence of women novelists. One of the genuine contributions of Dickens' Fur Coat is its illumination of the boulder-strewn paths that Charlotte and Emily Brontë (a.k.a. Currer and Ellis Bell), Marian Evans (George Eliot) and others had to travel.

An essay in the 1859 National Review, "False Morality of Lady Novelists," summed up the prevailing attitude: "Every educated lady can handle a pen ... therefore, [they] take to writing--and to novel-writing, both as the kind which requires the least special qualifications and the least severe study, and also as the only kind which will sell."

After six rejections of her first novel, Charlotte Brontë rewrapped the manuscript and sent it off to another publisher, crossing off the names and addresses of the publishers who had already rejected it. (The seventh try proved providential for both parties--along with a rejection, Charlotte got a letter of encouragement. She mailed back the just-completed Jane Eyre.)

Dickens found one way to beat the system; Eliot found another. Preparing a long "panoramic novel about the Midlands countryside" that could not be bent to suit the three-volume format, she decided to market Middlemarch (which clocks in at 799 pages in the Modern Library edition) in bimonthly installments of half volumes. The overwhelming success of Middlemarch helped Eliot achieve what Pool calls "a quasireligious status."

Indeed, the new popular novelists enjoyed a celebrity similar to today's media stars: "People cut fur off Dickens' coat; by their sheer numbers forced him to barricade himself in his hotel rooms; he hired a secretary to help him sign autographs, gigantic banquets were tendered him--it was all a new and delightful madness."

Dickens' Fur Coat is a juicy book on a dry subject. It's a bit depressing--but also reassuring--that vulgarity was as much a part of the Victorian library scene as our own. To paraphrase H.L. Mencken, no one went broke underestimating the taste of the Victorian public.

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

Victorian audiences created the first demand for high-profile novelists

Victorian audiences created the first demand for high-profile novelists

Dickens' Fur Coat and Charlotte's Unanswered Letters by Daniel Pool; HarperCollins; 265 pages; $25 cloth.

From the June 19-25, 1997 issue of Metro.