![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Movies Index | Show Times | San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Brilliant 'Sunshine'

Istvan Szabo's family epic is far from sunny, but dramatically rich

By Michelle Goldberg

A SEARING EPIC ABOUT three generations of Hungarian Jews, Sunshine delivers a forceful anti-assimilationist polemic without subsuming character and drama to politics. Although there are moments when the ideological contrivances are too blunt, there are many more when the film is entirely enveloping. It's a deeply depressing movie, but also a philosophically, dramatically and visually rich one.

Divided neatly into three parts, the film begins with Ignatz Sonnenschein, then follows his son, Adam, and Adam's son, Ivan--all three played by Ralph Fiennes. It's a risky move that could have come off like a coy gimmick, but it ends up working beautifully. Fiennes is better than he's ever been, creating three distinct characters who are nevertheless doomed to a common destiny. The fantastic costumes and art direction help--the film moves from the lush, genteel burgundies and bronzes of turn-of-the-century Europe to the utilitarian grays of the communist era, rendering the sweep of history in color and clothing.

Ignatz is raised with his brother, Gustave, and his orphaned cousin Valerie in a middle-class, religiously observant home. He becomes a judge, Gustave a doctor. In typical family-epic style, Ignatz is temperate and obedient while his brother is fiery and radical, and they eventually find themselves in opposition as a socialist uprising succeeds the monarchy's tolerant liberalism. Ignatz has only one rebellion: his love of the passionate, sensual Valerie, who becomes his wife and, eventually, the family's matriarch. (Valerie is played first by the divinely incendiary Jennifer Ehle and later by Ehle's mother, Rosemary Harris, giving the character an uncanny continuity.)

Early on, Ignatz, Gustave and Valerie decide to change their last name to something less Jewish, trading Sonnenschein, which means sunshine, for Sors, a Hungarian name meaning destiny. The switch is portentous. Even as Ignatz and his descendants try to escape their roots--Adam, a championship fencer, converts to Catholicism--their fates are tied to the tragedies of Jews in 20th-century Europe, and each man pays for his conformism. Adam wins a gold medal in the 1936 Berlin Olympics and thus believes himself exempt from the increasing oppression of Hungarian Jews. Because of his complacency, he misses his chance to flee the country, leading to the film's most shattering scene. Ivan spends his teenage years in a concentration camp. He emerges a devoted communist, lusting for revenge on Nazi collaborators. Despite his fealty to the Communist Party, though, he too finds his Jewishness will always keep him apart. Playing with the tension between the individuality of these men and their parallel fates, director Istvan Szabo (who won an Oscar for his 1981 film, Mephisto) illustrates the dehumanizing power of anti-Semitism. At the same time, he suggests that Jews themselves will find no solace in escaping from their history--the story seems to come full circle only when Ivan, disenchanted with communism, changes his name back to Sonnenschein. There may be a latent Zionist message in Sunshine, but on the whole the film's mix of empathy and bitter political fatalism recalls Milan Kundera's novels, which offer passion and insights, but no answers.

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![]()

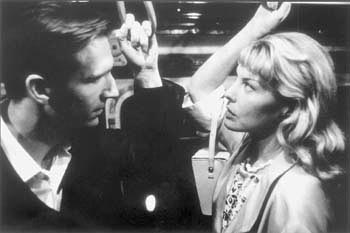

Hanging in the Balance: Ivan (Ralph Fiennes) and Carole (Deborah Kara Unger) share an intense moment.

Sunshine (R; 180 minutes), directed by Istvan Szabo, written by Szabo and Israel Horovitz, photographed by Lajos Koltai and starring Ralph Fiennes, Jennifer Ehle and Deborah Kara Unger, opens Friday at the Park Theater in Menlo Park and Camera One in San Jose.

From the June 22-28, 2000 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.