![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Movies Index | Show Times | Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

Photograph courtesy of Dog Eat Dog Films Pestering a Pol: The persistent filmmaker buttonholes pro-war Congressman John Tanner about how many representatives have kids in harm's way. Michael Moore on Fire Can the bad-boy filmmaker burn down the house of Bush with his incendiary new documentary, 'Fahrenheit 9/11'? By Geoffrey Dunn IT HAS BEEN 15 summers since Michael Moore crashed into the American mind-set with his iconoclastic and sardonic film Roger & Me. He will be burning into our psyche yet again this Friday (June 25) with a masterpiece of documentary cinema, Fahrenheit 9/11, an incendiary exposé of the Bush administration and its horrifically failed policies both domestically and in Iraq. The pre-release hype for Fahrenheit 9/11 has been smoldering for months. In early May, Moore and his new-found partners at Miramax, Harvey and Bob Weinstein, who financed 9/11, announced that parent company Disney, headed by Michael Eisner, was refusing to distribute Moore's film on the grounds that it was "too partisan" for the Magic Kingdom. Moore and the Weinsteins countercharged that due to favorable tax credits Disney received in Florida (a state prominently featured in 9/11 and, lest we forget, home to W's brother/governor, Jeb), Eisner was balking on the deal. Lots of ink was spilt on the controversy—and virtually all of it flowed Moore's way. The New York Times featured the issue prominently on its front page and later editorialized, "Give the Walt Disney Company a gold medal for cowardice for blocking its Miramax division from distributing a film that criticizes President Bush and his family. A company that ought to be championing free expression has instead chosen to censor a documentary that clearly falls within the bounds of acceptable political commentary." Eisner angrily responded that the Weinsteins knew all along that Disney wouldn't be distributing 9/11 and that their posturing was merely a publicity stunt. Besides, he said, the Disney Corporation caters to folks from all across the political spectrum and the company wasn't going to start taking sides now. Round 1 went to Moore and the Weinsteins. By the time the film premiered at the Cannes Film Festival on May 17, the hype had reached a crescendo. Fahrenheit 9/11 received an unprecedented 20-minute standing ovation and, a few days later, received the coveted Palme d'Or as the best film at the festival. It was the first documentary to win at Cannes since Jacques Cousteau's The Silent World in 1956. In the aftermath of their triumph on the French Riviera, Moore and the Weinsteins put together a unique distribution deal with Lions Gate Films of Canada, whose president, John Feltheimer, had worked closely with Moore on his TV Nation series, and with IFC Films, which aired Moore's TV show The Awful Truth, on Bravo. The word out of Hollywood and Toronto is that the film will open in more than 500 theaters nationwide, the largest opening for a documentary ever. The Republican right—which has reason to feel threatened by the revelations in Moore's film and the potential impact it will have on the November elections—has already issued a counterattack on 9/11. Groups including Move America Forward and Citizens United have threatened boycotts of theaters that screen the film and of the companies that partake in the distribution collective. They are also crafting video ads for television and the internet that slam Moore. Moore and Co. have countered with a worldwide grassroots movement to promote the film. The liberal advocacy group MoveOn.org is trying to counter the conservative campaign with mass mailings asking members to "pledge to bring their friends, relatives and neighbors" to "Fahrenheit 9/11" on opening night. Throughout it all, Moore has done his typical tap dance from moral indignation to biting humor. "The right wing usually wins these battles," he posted on his website (www.michaelmoore.com) last week. "Their basic belief system is built on censorship, repression and keeping people ignorant. They want to limit or snuff out any debate or dissension. They also don't like pets and are mean to small children. Too many of them are named 'Fred.'" Expect Round 2 to go to Moore and the Weinstein's as well. Burn Marks Michael Moore has always had serious detractors from across the political spectrum. A practical populist, rather than a radical ideologue, he's not afraid to mix it up with critics from the left or the right. One of the rumors coming out of Cannes was that 9/11 won the Palme d'Or not because it's a great film but as a result of French political animus for Bush and the war in Iraq. There were further inferences that Miramax's resident auteur, Quentin Tarantino, who headed up the Cannes jury, carried the Weinsteins' water by lobbying strongly on behalf of 9/11. That, I can assure you, is unadulterated merde. Fahrenheit 9/11 is Moore's most mature and nuanced film to date, and certainly his most ambitious: by taking on "the leader of the free world" and trying to bring down his international reign of terror, Moore has raised the stakes in this film perhaps higher than any other director ever has. Fahrenheit 9/11 is a work of revolutionary cinema. Literally. I attended an advance screening of Fahrenheit 9/11 in San Francisco last week, and I entered the small theater on Market Street with cautionary anticipation. I have often been troubled by the "cinematic license" (fudging facts and timelines) employed by Moore in his earlier films and by his self-congratulatory and egocentric posturing. It's all made, admittedly, for some hardy laughs, but most of them were cheap and many of them misdirected. And they came, I believe, at the expense of Moore's larger political message. There's nothing cheap or misdirected in Fahrenheit 9/11. The film goes straight for the jugular. And it draws blood for the better part of two hours. The title of Moore's latest polemic is a play on the fabled Ray Bradbury classic, Fahrenheit 451 (and the François Truffaut film of the same title), in which all books are burned in a post-utopian society (451 degrees Fahrenheit is the temperature at which paper burns). "Fahrenheit 9/11," says Moore, "is the temperature at which freedom burns." The film dices up the Bush Administration from the 2000 election debacle right through to the most recent revelations from Iraq. It's a tour de force of montage cinema--the juxtaposition of imagery creating a message far greater than the sum of its parts. It presents Bush not only as an incompetent leader--by now that conclusion is hard to escape--but as arrogant, vapid, condescending, mean-spirited and lazy as well. It is not an endearing portrait. Michael & Me For those who have been sleeping in the Catskills for the past two decades, Michael Moore is the prodigal son of Flint, Mich., in the heart of the U.S. auto industry. During his adolescence, Moore attended a seminary, but politics and rock & roll soon competed for his attention. He re-entered the secular world of high school, earned an Eagle Scout badge, graduated in 1972 and later attended the University of Michigan for part of a year before dropping out, as he is wont to claim, because he couldn't find a parking space on campus. Moore never worked on the assembly line (a blue-collar life was not to be his), but he became a political rabble-rouser in Flint and soon founded a weekly newspaper, the Flint Voice (later the Michigan Voice), which he helmed for the better part of a decade. In 1986, he left the Voice to assume, at the age of 32, the editorship of the liberal monthly magazine, Mother Jones, then headquartered in San Francisco. It was not, to put it mildly, a match made in heaven. Moore and I had a mutual friend at Mother Jones at the time, and through her, it was proposed that I write an article on the decline of the West Coast fishing industry, in which I had been raised, much as Moore had with auto production in Flint. A meeting was arranged, but Moore was canned before it ever took place by M.J.'s aristocratic publisher, Adam Hochschild. Moore claimed that he had been fired because he opposed the publication of an article by Paul Berman critical of the Sandinista government in Nicaragua; Hochschild claimed that he fired Moore for "inadequate job performance." The firing became a cause célèbre on the American left, while Moore had his first real taste of national notoriety. He left San Francisco dejected, but equally determined, and eventually won a $58,000 wrongful termination settlement from Hochschild. By then, Moore had moved back to Flint and quickly put his settlement on the line; he decided to make a movie about the G.M. plant closings in his hometown, the relocation of union jobs to Mexico and the devastating impact the plant closures had on his community. Moore was a man on a mission. It was on Sept. 1, 1989, that Roger & Me, largely unheard of prior to its initial screening, premiered at the influential Telluride Film Festival. It was an instant hit. Over the course of the next several months, the film played to huge ovations at the Toronto and New York film festivals. Moore was quickly becoming an ascending star in the big-time world of American film. Vincent Canby of The New York Times declared that "America has an irrepressible new humorist in the tradition of Mark Twain and Artemus Ward. ... Roger & Me is rude, rollicking ... witty ... leaving the audience roaring with laughter." Moore's celebrated independent film agent, John Pierson, capitalized on the media frenzy and ratcheted up the bidding war on Roger & Me (a process celebrated in his book Spike, Mike, Slackers & Dykes), and eventually secured a $3 million advance for the film from Warner Bros., a figure positively unheard of in the world of documentary. Not everyone bought into Moore's shtick. The New Yorker's Pauline Kael responded acerbically to Canby's praise by declaring that "the film I saw was shallow and facetious, a piece of gonzo demagoguery that made me feel cheap for laughing." More troubling to me, however, were the underlying politics of Roger & Me. Moore, as is his penchant, focused his moral outrage on a single individual, G.M. president Roger Smith, rather than on corporate capitalism. It was the individual that was to blame, not the system. As Larissa McFarquhar noted in a recent profile of Moore in The New Yorker, "For Moore, everything is personal." It's why, ultimately, Roger & Me didn't pose a threat to Warner Brothers and the film industry and why it was embraced by the mainstream media. Moore's message in the film was reformist, not radical. Moore weathered the criticism all the way to the bank. The film was a runaway hit at the box office (Moore would later claim a gross figure of $25 million, while Pierson contends it was half that much). Either way, he had become a media sensation. His moment on the American stage was to last much longer than 15 minutes; he had become a cultural icon. Green Day Moore's next film project was an unabashed failure, a pathetic comedy called Canadian Bacon, starring Alan Alda, John Candy and Dan Aykroyd. He also tried his hand at cable television comedy in the '90s, first with TV Nation (1994) and later with The Awful Truth (1999). Both relied heavily on the Moore formula developed in Roger & Me, but they never quite found their respective audiences. Timing, as they say, is everything in show biz, and that may have been Moore's undoing with the TV shows. I think that Roger & Me, coming as it did at the end of the Reagan era, served as a corrective balance to the Reagan myth of a reborn America and called lie to the pretense of widespread prosperity. During the Clinton era, however, Moore's voice was less urgent, his message more muted. In 1996, Moore published the first of several books, Downsize This!, which quickly climbed its way onto The New York Times bestseller list. The following year, Moore came back with another documentary, The Big One, a solid documentary on the internationalization of the world economy by corporations like Nike. It didn't quite go boffo at the box office, but it was a moderate critical and financial success and got Moore back in the movie game. With Downsize This! and The Big One, Moore had found his audience--the disenfranchised Generations X and Y--the twenty- and thirtysomethings who were dropping out of the political process, alienated from both major parties, and who were taking to the streets in protest of the globalization of American capital. It was essentially a Green political agenda, and Moore—who has always been something of a cross between the Pillsbury Dough Boy, P.T. Barnum and H.L. Mencken—had become its principal polemicist. While it placed him moderately at odds with the Clinton administration and the mainstream of the Democratic party (largely due to free-trade initiatives like NAFTA), it nonetheless secured for him a solid and unyielding audience base.

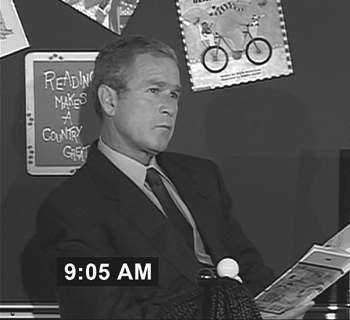

Guileless Goat-Boy: Even after learning that the World Trade Center had been attacked, President Bush continued to read 'My Pet Goat' to a room of schoolchildren. Enter W The contested election of Bush fils for the presidency, ironically, thrust Moore back to center stage in American political theater. He became one of the country's most vocal critics of the Bush administration, challenging its domestic and foreign policy initiatives in the wake of 9/11 in ways that timid Democrats refused to initiate. Moore's book Stupid White Men (2001) spent more than a year on the Times bestseller list (59 weeks), and he followed it up again with yet another No. 1 bestseller, Dude, Where's My Country? (2003). His 2002 documentary Bowling for Columbine, a scathing, if muddled, exploration of gun violence in the United States in the aftermath of the Columbine High School slayings, earned a cool $20-plus million at the box office and won Moore an Academy Award for Best Feature Documentary. At the Oscars, Moore set the stage for the launch of his new film when he declared: We live in fictitious times. We live in the time where we have fictitious election results that elect a fictitious president. We live in a time where we have a man sending us to war for fictitious reasons ... Shame on you, Mr. Bush, shame on you. Michael Moore was a cause célèbre once again. Little more than a year after his Oscar triumph, Moore is now back in the cinematic limelight. By the time Fahrenheit 9/11 opens, the buzz of publicity over the last few months will have become a roar. I won't be surprised if angry audiences take to the streets in response to the film; I am sure they will make their way to the nation's voting booths come November. The film opens with a rehash of the "stealing" of the 2000 presidential election and the vote-counting debacle in Florida. It's familiar terrain that's been covered before. Indeed, we saw it happen before our very eyes, watched it on the networks and CNN and whatever cable channel we happened to surf onto. But when Moore juxtaposes archival network coverage of the contested election with an airplane interview with Bush in which the then-candidate emphatically declares, "We are gonna win Florida; write it down!" one can't escape being sickened by the realization that the fix was in from the get-go. Then Moore cuts to none other than the defeated Al Gore, in his capacity as president of the Senate, presiding over the ratification of the 2000 election. As several Asian American and African American members of Congress attempt to protest the results of the stolen election, a cardboard Gore gavels them to silence because not a single member of the Senate would sign their protest. This early dig at Gore (whom Moore did not support in 2000; he supported Nader) and the Senate Democrats lends an air of credibility to the film that it wouldn't otherwise have. It's as if Moore is signaling to his audience that his moral outrage is bipartisan. In my mind, it makes what follows all the more powerful. What's fascinating about Fahrenheit 9/11 is that little, if any, of the "revelations" in the film are new. Indeed, most of them are covered in Moore's Dude, Where's My Country?, particularly in its opening chapter, "Seven Questions for George of Arabia," replete with 97 footnotes. It's also covered in far more depth in House of Bush, House of Saud, by Craig Unger, who's interviewed in the film. But it's one thing to read about the Bush family's cozy financial links to the Saudi government and the bin Laden family (Unger asserts that they have enriched Bush and his family associates with $1.4 billion), and it's another to see so many news clips and photos of the Bushes and their Saudi cronies cavorting together. Then there's the footage of President W. on the fateful morning of Sept. 11, 2001. Bush was in his brother's domain of Florida, on his way to an elementary school photo-op, when he was informed of the first plane crash into the World Trade Center; he continued to the school. He was in the middle of reading My Pet Goat to the students when an aid walked in and informed him of the second attack. Moore got footage of Bush's visit to the school from a teacher. Contrary to the official line that Bush left immediately following news of the second attack, the clip reveals that Bush stayed for an additional seven minutes—the vapid, muddled look on his face is absolutely disquieting, given the seriousness of the events—before he got up to leave, not on his own initiative, but at the suggestion of another staff member. The footage is indelible. Perhaps the most haunting images from the film (cut very similarly to the opening sequence of Errol Morris' Fog of War) are those of the überbrokers of the Bush Administration—Donald Rumsfeld, Dick Cheney, John Ashcroft, Paul Wolfowitz, Colin Powell and Condoleezza Rice—having their hair primped and makeup applied in slow motion as they await appearances on television. (Wolfowitz actually sticks a comb in his mouth to wet his hair, then spits on it again before the camera.) The sequence made my skin crawl. This is, of course, the power of documentary film—the sense of experiencing actuality firsthand. There is a bond, or an assumption, in documentary construction between the filmmaker and his or her audience that what's being seen on the screen, while edited and constructed, is largely unmediated. The power of documentary is lost when that bond is broken. Moore has broken it in several of his other works. Not so in Fahrenheit 9/11. Nor does Moore go in for his traditional cheap shots in 9/11. His sarcasm is more subtle, his humor more tempered. This is a serious film, and Moore fully respects the gravity. There's a little dig at Britney Spears (who really cares what she thinks about Bush?) and Moore reads excerpts of the Patriot Act over a loudspeaker from an ice cream truck, but Moore's often troubling trademark shtick is kept to a minimum. He lets the images themselves make their case.

Uniform Justice: Moore and Sgt. Abdul Henderson visit Capitol Hill to see if they can talk our representatives into sending their own kids into battle. Closing the Gap The ultimate question on everyone's mind in the days leading up to the release of Fahrenheit 9/11 is: How good of a case does it make? Will it be compelling enough to impel American voters to throw George W. Bush out of office? Many of my friends on the Democratic left view Moore with suspicion. They were angered by his support of Nader in 2000, and they are none too happy that he has yet to support John Kerry. (I suspect Moore is waiting to do so for theatrical effect, but who knows?) Conversely, many of my friends in the Green Party were outraged that Moore endorsed Wesley Clark in the Democratic primary. He did so, he declared, because he thought that Clark could beat Bush. In a matter of four years, Moore had gone from an idealistic Green to a peculiarly pragmatic Democrat. Go figure. But I would suspect that George W. Bush is at the heart of Moore's political alchemy. Fahrenheit 9/11 does not, indeed, make the case for the election of John Kerry. That, I would argue, is Kerry's case to make, not Moore's. And I believe that much of the strength of 9/11's compelling brief against Bush comes from the fact that Moore did not endorse Kerry. It lets the audience come to its own conclusion. One film, of course, does not a campaign make. Please excuse the sports metaphor here, but if the election were a football game, Moore has taken out a solid portion of Bush's front line and Kerry should have an open field in which to run. The Bush team will be spending a considerable amount of energy in the months ahead trying to close the gaping hole created by Fahrenheit 9/11. But as anyone ever involved in politics knows, it's a long time between the Fourth of July and election day. A lot can happen. Whether John Kerry captures the imagination of the American electorate will be up to him and the Democrats, not Michael Moore. In the interim, I would not want to be George Bush come Friday. He will not be a happy camper. Fahrenheit 9/11 was made with the clear intention of stripping him of his presidency. I think that it will have a powerful impact on his fate. The proof of that particular pudding will come next November.

Longtime Metro Contributor Geoffrey Dunn's latest film, 'Calypso Dreams,' is being honored next week by the United Nations' World Conference on Culture in São Paulo, Brazil.

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com. [ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

|

From the June 23-29, 2004 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.