![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

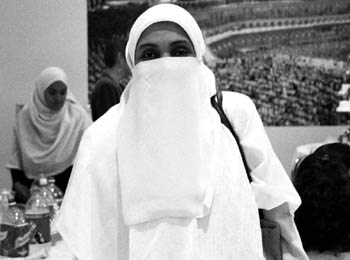

Ill Advised: George Bush was the American Muslim choice in 2000. Many are now saying they got bad information. Invisible Men Once a footnote to electoral history, Muslims are growing politically in America but in what direction? By Najeeb Hasan LAST SATURDAY, in a San Jose Convention Center meeting room, about 150 members of the South Bay's Muslim community gathered expectantly for a South Bay-wide Muslim town-hall meeting. The meeting, sponsored by the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), would be one of 40 such meetings scheduled in major cities across the nation by the American Muslim Task Force, an umbrella group of nine American Muslim political organizations. The nation's 7 million American Muslims, still undeniably nascent in their political identity, are perhaps best known politically for their bloc vote in the 2000 presidential elections, when some polls showed that an overwhelming 72 percent of Muslim Americans voted for George W. Bush. Four years and two wars later, Muslim political organizers have found themselves frantically organizing another bloc vote, this time with the specific intention to unseat the administration they helped vote in four years ago. CAIR organizers brought in a heavyweight political cast, including Zoe Lofgren, Art Torres, Ralph Nader, Grover Norquist (via telephone) and San Jose Mayor Ron Gonzales, to greet the Muslim audience Saturday afternoon. The meeting, according to activist Agha Saeed, would help answer one of the more puzzling questions for political observers: Other than the obvious foreign policy and civil rights issues, what, exactly, are American Muslim political issues? The eventual answer to that question will help distinguish whether American Muslim organizers intend to steer their community toward a narrow, issue-centric political identity—a trap that other religious communities have certainly fallen into—or a broader, issues-centric identity. As it stands, the rest of America can guess fairly accurately the Muslim take on the Israel-Palestine question, the occupation of Iraq and the Patriot Act, but few would have the slightest idea about what Muslims think about the budget deficit, gun control, urban planning, health care or any number of other issues. "I think the community as a whole is not very sophisticated politically," says Umar Faruq Abd-Allah, a Chicago-based academic. "Political action that is more effective is based on municipal and local politics, bottom to top, instead of working from the top to the bottom. Muslims have this preoccupation with foreign policy issues, issues many Americans have had a preoccupation with before. But you have to be involved with internal politics before your voice becomes credible on that stage." CAIR chairman Omar Ahmad opened Saturday's proceedings by listing the most important American Muslim issues; among them, he cited Muslim inclusion in the political process, civil rights, a balanced foreign policy in the Middle East and the need for the United States to have a better relationship with the Muslim world. The issues were straightforward, predictable (but certainly necessary) and, in some senses, narrow—two involved foreign policy and a third was a reaction to bad legislation. Meanwhile, two hours later, when Nader addressed the audience, he ticked off his own list of issues he thought Muslims should concern themselves with: the Patriot Act, the need to use Muslim identity to battle crass, corporate-driven popular culture, voter registration, the occupation of Iraq, the Israel-Palestine issue and the national budget deficit. (Nader was the first and only speaker to mention Israel by name during the event.) Nader—himself of Christian Arab descent—managed to put forward a more creative platform for Muslims than the Muslims themselves. What gives? "Basically they [CAIR and Nader's platforms] are the same," Ahmad responds. "I think he put them in different words. He highlighted the corporate culture and the deficit; what we're saying is we look at it from [the perspective of] an outsider trying to get in. We're saying we should be included to talk about these issues. So it's a matter of timing rather than a matter of whether we care about them or not. How can I discuss the deficit when I'm not even given a seat at the table?" Bloc'd In In the Bay Area alone, there are estimated to be more than 100,000 Muslims, 30 mosques and 15 different Muslim organizations. The Eid prayers for the South Bay's two largest Muslim organizations—the Muslim Community Association in Santa Clara and the South Bay Islamic Association in San Jose—each attracted more than 10,000 worshippers. Nationally, according to numbers collected from the American Muslim Alliance, an organization dedicated to electoral politics, 700 Muslims ran for public office in 2000, and 153 were elected. Today, there are six American Muslims holding state-level seats. The AMA also uses numbers from one of former Rep. Paul Findley's books, which claims there are about 4.2 million Muslims registered to vote in the nation. Agha Saeed, who heads up the AMA out of its offices in Newark, has been for the last decade one of the leading advocates of Muslim inclusion into the American political process. On defining Muslim issues, Saeed takes the easy way out. "I think the question has been answered remarkably well by Dr. Maher Hathout," he says. "When somebody said, What's a Muslim issue?, he said, Name one thing that benefits humanity and is not a Muslim issue. So we believe whatever is beneficial to humanity is a Muslim issue." Saeed's answer, though, begs another question: If Muslim issues are indeed "humanity's" issues, what's the point of having an American Muslim Alliance? For Saeed, the answer is twofold: to maintain an American Muslim identity and to reach into and educate the American Muslim community. In 2000, Saeed was the chair of the organization that cajoled the Muslim electorate to vote Bush. Politically, Saeed, who now advocates a civil rights agenda, has no regrets. The issue Saeed and other Muslim activists were concerned with in 2000 was the federal government's ability to imprison [mostly Muslim] suspects indefinitely based on secret evidence. Bush was the only candidate, says Saeed, who would agree to speak out against the practice. "At that time, the Democratic Party gave us a cold shoulder completely," Saeed recounts. "The only candidate who was willing to meet with us was Bush. We met with him. We presented him the issue; we told him very clearly that we are looking for some kind of alliance, but we would not do it if it was only some kind of assurance in a meeting room. What we would like to have is that pledge translated into a public statement during the presidential debates. So in the second presidential debate, if you go and look at it, Bush said that if elected I'm opposed to profiling of blacks and Arabs—he didn't say Muslims. And secondly, he said if I'm elected I will support an effort to repeal the Secret Evidence Act. That was the public position he took on that issue. We believe by getting him to say that, we put our issue on the map of the presidential agenda. That was a remarkable success for a community of less than 2 percent of the population. Muslims to this day are seen as politically relevant." However, the support of Bush highlights the problem that Muslims are still grappling with as young political community. If your issues are brought up on a national stage, that sounds good, but how politically relevant are you if those same issues aren't addressed after that? "A lot of us did vote very unfortunately and very ill-advisedly [for Bush]," says Abd-Allah. "Muslims like to say—and they may be correct—that Muslims certainly did play a role in electing Bush and Cheney in the last elections. But they were instructed to vote for them, which really shows a tremendous lack of sophistication on the part of those particular organizations who took that position. They were being told that they needed to form a political identity as Muslims in the United States. I would like to see a political identity not based on opportunism and particular issues but based on a principled conviction to civil rights [and a] commitment to Constitutional law and the rule of law." Saeed counters that the endorsement was not a mistake. Rather, he says, Sept. 11 changed everything. "Any serious analyst cannot think of these things without looking at what Sept. 11 was, what it has done to the American psyche, how it has changed the direction of American administration and how it has created a totally new coalition of forces in this country, many of whom are against Muslims," argues Saeed. "So what Sept. 11 did was, where we had gone from 1990 to 2000 [as a political community], we had traveled a certain distance; 2001 took us not only to the starting point but pushed us behind it." Not all of the organizers of the Bush vote take Saeed's unapologetic stance. "I think the criteria that Muslims set for that first election did not include any bigger issues," says one person involved in the negotiations. "That was probably the issue. Maybe the criteria for selection was very narrow and very specific. I really believe that, and I was one of those who participated in making that decision. I think the issue was to make Muslims active in politics. It was an exercise. Did we believe this election would make a true difference? We did not see it that way. We saw it as we just kind of pushed the community into the field. It's like teaching children how to read."

Hot Buttons Perhaps one of the more tricky positions for Muslims in the American political scene is tackling the hot-button socially conservative issues, such as abortion and gay and lesbian rights. As Muslims in the United States are struggling to defend their civil liberties, they, as a result of their socially conservative identities, find themselves taking the opposite position of their liberal defenders on these issues. Social conservatism, Saeed says, was another reason Muslims were attracted to Bush in 2000. "In small ways, yes, this is a difficult political position," Saeed acknowledges. "But what I think is really interesting and instructive to see is how quickly Muslims are learning to live with these things. There's a person elected to a city council in Texas who was at the meeting in New York that I spoke in. He said Muslims should be at the forefront of defending other people's rights, including gays and lesbians. There were about 60 people in the room, and there was a palpable silence in the room. Now, nobody endorsed him, but nobody opposed him. A couple of years ago, there would have been a huge cry in the room. People would have challenged him and reprimanded him. That did not happen. So what is happening is that the struggle for civil rights is teaching Muslims a new kind of sophistication and a new kind of sensitivity. Democracy is learning the art of living with people you don't agree with. I think Muslims are learning it, and learning it in a very impressive fashion." Abd-Allah, meanwhile, warns about the dangers Muslim identity could face by focusing on issues based on ideology. "The way that the religious right works right now, these hot button issues are tagged on to other political agendas in such a way that they alienate people with other agendas, and they win other people who have no business being there in the first place," Abd-Allah says. "Moral issues are brought into the political process to bring voters to vote for parties that do not represent their economic interests. The beneficiaries of the last elections represent a very small amount of people. We and a lot of other religious communities who have liberal sentiments and still hold to their religious values need to look at it another way. I think that what American democracy is based on is a public trust, which is an agreement that we can live together because of shared interest. I would like to see ultimately that these hot button issues not be hot button issues, including for gays and lesbians. [Muslim political identity] needs to be met without making it necessary for our community to be on board with the liberal agenda."

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com. [ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

|

From the June 23-29, 2004 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.