![[Metroactive Music]](/music/gifs/music468.gif)

[ Music Index | San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

It's Not Easy Being Nice

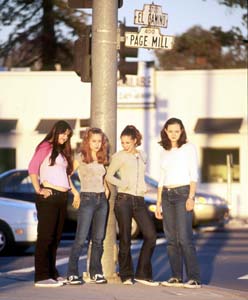

Name to Fame: Formerly called the Electrocutes, the band found fame as the Donnas, where they created stage names (from left) Donna C., Donna A., Donna R. and Donna F.

Name to Fame: Formerly called the Electrocutes, the band found fame as the Donnas, where they created stage names (from left) Donna C., Donna A., Donna R. and Donna F. Greg Roden

When good old teenage rock & roll goes out of fashion, only girls will keep the music alive. Palo Alto's Donnas just want to party By Michelle Goldberg THE DONNAS ARE not the types to demolish hotel rooms. It's easier, in fact, to imagine them giggling over room service. Some Donnas fans, in fact, would be disappointed if they knew how nice the members of the hedonistic, hard-edged nymphet quartet from Palo Alto really are. Although the Donnas are hurtling toward stardom--they have scored photo and story spreads in Spin and Rolling Stone, will soon embark on their second European tour and are about to release their third album, Get Skintight--offstage they can only be described as sweet and self-effacing. Talking to the Donnas, I kept wanting to interject, "But don't you realize that you're famous? Don't you feel like you're on top of the world?" But the Donnas, one 19-year-old and three 20-year-olds, are strenuously down-to-earth. Although they're forever being compared to Joan Jett and Lita Ford, these four are more about fun than fury. If anything, their music resembles the goofy defiance of the Beastie Boys singing "Fight for Your Right to Party" more than Courtney Love bellowing "Teenage Whore." Even though they still have to cope with industry sexism, the Donnas seem to suffer much less dissonance about being girls with guitars than their predecessors. They don't have to assume the impenetrable cool of a Chrissie Hynde or the open-wound hysteria of a Courtney Love to reconcile themselves to being exiles in guyville, because rock isn't all about boys anymore. Nor is pop about rock anymore--which is why the Donnas can be one of the most rapidly up-and-coming rock bands in America and still see themselves as almost marginal. Other kids the Donnas' age don't worship them for being rock stars, because they don't worship rock stars period. "People will be like, 'You think you're so cool because you were in Spin or Rolling Stone, but I don't think you are. I'm still not impressed,' " says guitarist Donna R., known in the real world as Alison Robertson. "We weren't discriminated against because we were girls. We were discriminated against because we were in a band. We were never cool anyway, and it wasn't because we were girls. It was because we were us." Baptism of Sarcasm ALL OF WHICH may explain why the Donnas aren't nearly as egomaniacal as almost anyone else would be in their dream-come-true situation. Most stars seem to get drunk on audience adulation, but Robertson still has a particularly vicious crowd etched in memory--one made up of other high school kids. As we sit together at Bimbo's, a huge, teeming San Francisco nightclub, just before the Donnas' CD-release party, Robertson thinks back to the group's first night-time gig, four years ago, at a community center not far from drummer Torry Castellano's (Donna C.'s) house. The place was full, she recalls, and kids in other bands who had always teased the Donnas ceaselessly were suddenly cheering for them, but Robertson was convinced they were joking. To hear Robertson tell the story, the dynamic sounds like a rock version of the prom scene in Carrie, where the high school elites savored the outcast girl's social ascension only because it would make her humiliating fall all the steeper. "Usually those shows aren't packed, and usually everybody stays away from the stage," Robertson says, "but at this show, since everyone wanted to make fun of us, it was like nobody wanted to miss this. They were crowded in front of the stage, but we knew it was sarcastic, so we were dreading playing." But the Donnas were good. Not just good for a high school band, but good period. Mocked by their peers for years, they'd been spending every afternoon since junior high in Castellano's garage, practicing endlessly and getting so tight that jealous insults bounced right off of them. "I thought we were going to be awful, because I was so nervous. I remember I was going to puke, thinking everybody's out there, everybody's cheering but it's totally sarcastic. But we actually kicked ass. After the first song, everyone liked us." It sounds like a triumph, more than enough to catapult the foursome to the top of the social hierarchy. But it didn't work out that way--the next day at school, everyone pretended that the show had never happened and went back to tormenting the Donnas as usual. Journalists, they say, always ask whether other kids kiss their asses now that they're famous--probably because they want to see the Donnas fulfill their own fantasies of avenging themselves on high school tormentors through media stardom. What adolescent misfit didn't dream that the outside world would one day recognize her genius and whisk her away from her oppressive little suburb? The Donnas, after all, had to take time off high school to go on their first Japanese tour--how much cooler can you get? It seems that they've proved themselves 10 times over. But other kids, especially boys in other bands, didn't show the band respect, and often they still don't. Contempt may have transmogrified into envy, but the end result is the same. When Robertson and bassist Maya Ford (Donna F.) went to UC-Santa Cruz for a semester before dropping out to devote themselves to the band full-time, no one wanted to be friends with them. No one. "We got attitude from everybody," Robertson tells me. "I used to go to the bathroom as far away from our hall as possible to get ready for bed every night, because I just didn't want to see anybody." Ford seconds the bitter memory: "In the dining hall, there were all these huge round tables for everyone to sit at--there's room for eight people--and we'd always go and sit at a table all alone, and no one would ever sit with us." No matter how acclaimed they get--or how good--the Donnas are forever dogged by disrespect. And not just in high school, either. Though reviews of their records have generally been rapturous, writers still have difficulty taking them seriously. Carly Carioli wrote in the Boston Phoenix, "Rock & roll isn't about sex and drugs and speed even when it's about sex and drugs and speed--it's about gestures/winks/shorthand. Their gestures: nympho jailbait jukebox revenge, streetcorner everygirls playing dress-up with Gene Simmons' libido." Natalie Nichols said in the Los Angeles Times, "[T]hey aren't fully aware that much of their charm, for better or worse, is tied to their being Chicks Who Rock."

Driven to Distraction: The members of the Donnas (left to right)--vocalist Brett Anderson, guitarist Allison Robertson, bassist Maya Ford and drummer Torry Castellano--say they were outcasts at their Palo Alto high school. Svengali Rock WORST OF ALL, though, is the rumor that the Donnas were solely the creation of a Phil Spector-like impresario named Darren Rafelli, a Palo Alto man whose tiny label Superteem issued the first Donnas album. Thirty-three-year-old Rafelli first saw the Donnas as 15-year-olds when they were playing a gig as the Electrocutes--the girls' first band--at the Chameleon, a grungy club in San Francisco's Mission district. Rafelli had been writing songs for an imagined girl group, and he asked the foursome if they'd like to record some of them. At first, their parents were skeptical--what does this older man want with our daughters?--but after forcing the girls to bring a male friend to their first session, they eventually grew convinced that Rafelli's intentions were honorable. He wrote all the songs on the Donnas' self-titled debut album and collaborated with them on their second, American Teenage Rock n Roll Machine. He quit his job to accompany them on their first tours, both domestically and to Europe and Japan. But both Rafelli and the Donnas grew tired of the popular perception that he was some kind of Kim Fowley and the Donnas his latter-day Runaways, and so they parted amicably before the Donnas wrote Get Skintight. Though they're still close--they had dinner together before the Bimbo's show--the Donnas are battling the idea that they were his pawns. "People don't think that young girls can write songs," Robertson notes, "and so they think that if there was someone involved he was totally in control of everything all the time. We didn't write our songs for two years out of our six years as a band, which means we've written songs for four years. Now we're writing songs alone again. So if people want to keep making fun of us, they can make fun of those two years of our career." Lilith of the Valley DESPITE THEIR essential apoliticism, the Donnas have run smack up against the alternately exalted and degraded status of women in rock--and of rock more generally. What with the Lilith Fair, the riot grrrls, Courtney Love, Ani DiFranco, Alanis and dozens of other female icons, we seem to be at a uniquely gynophilic moment in pop music. But girl bands still routinely get treated like gimmicks, analyzed according to their hairstyles instead of their albums, or denigrated as the puppets of some male Svengali orchestrating their act--the story that has especially haunted the Donnas. "For guy bands, it's kind of hard to get recognized in the first place, but once they do it's a lot easier for them to get respect," says vocalist Brett Anderson, known as Donna A. "When people talk about guy bands that they like, they'll say, 'Oh, they're such great musicians; they write such great songs.' With us, it's never the first thing that people say. It's about our image or our attitude." Beyond all that, rock itself can no longer take its own relevance for granted. Rock is a youth music that's no longer young, one that's largely been supplanted in the hearts of high school kids by techno and hip-hop. In one of our culture's mean little ironies, women have flooded into rock precisely when rock itself is waning. Are girls with guitars less threatening now because less is at stake--because the MC's mic and the DJ's needle are the new pop phalluses? Or are females breathing new life into music that's already exhausted all the emblems of male rebellion and machismo? Are the Donnas part of rock's future or its past? Critical paeans to the group tend to emphasize how they remind listeners of their halcyon, hedonistic adolescences. (Never mind that "halcyon adolescence" is virtually an oxymoron.) "Hanging with the Donnas is like being in detention with all your best friends," coos Jancee Dunn in Rolling Stone. To me, though, the Donnas are to high school what Grease was to the '50s--they remind me of the youth I wish I had, not the excruciating messy misery that marks most people's young lives. The Donnas rocketed to success by tapping into the myth of the American teenager, not the reality. Now that they're well past graduation, though, one of their challenges is going to be transcending their association with high school--something they've already started doing on Get Skintight, which often sounds like a brash shout of freedom after four years of confinement. With Get Skintight, they've seized on a new romantic American archetype--that of rock & roll itself. Since the Donnas are giddily celebrating rock & roll at a time when no one's sure whether rock has any steam left, the world they sing about doesn't bear much relation to the one we live in. Instead, their music is quintessentially escapist--both in the obvious party-all-the-time sense and in a more subtle way that defies the current rules of cool. They lust after boys in tight jeans when the new emblem of hip is the DJ in ghetto baggies. That's why it's no surprise that the Donnas' first fans were largely adult men, that people their own age didn't know what to make of them. Sure, some of them were thrilled at watching sexy young girls tear up the stage, but the older fans' affection seems more wistful than prurient. "I've been following their career from the beginning," says a grizzled, balding ex-punk smoking a cigarette outside Bimbo's. "They make me feel like I used to feel in the '70s!" "People think we don't understand what we're doing," Anderson says. "They think we're playing this kind of music that we don't really know anything about, that we don't understand why people like us. They think that we sort of lucked out, and that we were doing this thing and everyone likes it, but not because we deserve it, or because we planned it that way." The Donnas' music is deceptively simple--hyperactive, hook-heavy rock & roll with driving guitars and silly, hedonistic lyrics that are often totally self-referential. "Turn up the music you can make me all right/We're gonna get it Friday fun tonight," Anderson sings on "Skintight," the new album's opening track. Other songs continue in this vein. "Rock & roll all weekend long/It starts Friday at the break of dawn," she shouts in "Doin' Donuts," while on "Party Action," she sings, "This party started out so PG-13/I think it needs a little rock & roll machine." Their personas are familiar, too--sexy tough girls who like to party, who want boys but don't need them. The band's lineage weaves together several strands of pop history--the girl-group harmonizing of the Shangri Las, the nubile juvenile delinquency of the Runaways, the bubblegum glam of Blondie. It's hard to know just how much irony is at work here--though their songs profess indifference to school, these girls are smart and savvy. Teenybopper pop, of course, was an essential element in the punk pastiche of New York bands like Blondie and the Ramones, so with the Donnas there's a kind of double remove. But the Donnas' appeal is immediate, not ironic, even if they do tend to evoke nostalgia in middle-aged listeners. Their professions of love for bands like Kiss, Mötley Crüe and Poison sounds like a kitschy joke, especially since so many groups take such perverse joy in resuscitating oft-disparaged musical genres--the lounge movement, for example. But then you hear that the band jumped at the chance to open for those big-haired, blue-collared purveyors of monster ballads, Cinderella, in Reno of all places. And on their new album, they've moved toward a kind of arena-rock sound, replete with the cocksure electric guitar solos so hated by punks of old. In fact, one of the Donnas' goals is to bring back old-fashioned rock & roll. Says Ford, "Maybe we can help the new generation of kids learn that rock & roll is the type of music to like. Most kids only want to buy the Backstreet Boys and pop music, and if we get bigger we can change that. All the videos on MTV aren't really rock songs, they're all kind of alternative or rap or pop songs. I'm not saying that's bad, but rock has been overlooked for a while and somebody's got to bring it back." Adds Anderson, "People don't have to like only rock, but it shouldn't be forgotten."

Greg Roden

Lunch Money THOUGH DARREN RAFELLI was instrumental in launching the Donnas' career, they'd already been a band for two years when they met him as 15-year-olds. When they were in eighth grade at Palo Alto's Jordan Middle School, there was a lunch-time concert for school bands, and best friends Robertson and Ford were angry that only boys seemed to be playing. The two of them had been practicing guitar and bass for a few months, playing R.E.M. songs with a drum machine. A month before the midday show, they recruited Brett and Torry, neither or whom had any kind of training. Calling themselves Raggedy Ann, they played Muffs, Shonen Knife and L7 covers in front of their classmates and had so much fun that they started practicing every day. Later on, they changed their name to the Electrocutes, and their junior year they recorded an album, Steal Yer Lunch Money, which they just released last year. Harder, faster and rougher than the Donnas, the Electrocutes' album is a furious, exuberant exercise in thrash. There's a surprisingly sophisticated sense of humor in its absurdist lyrics, especially the hysterical recitation of frosty drink recipes in "Daquiri Jacquerie" and the refrain that could serve as a motto for the Donnas' bad-girl personas, "It's hard to be nice/not that I try." Initially, the Donnas were conceived of as a side project. When the girls started working with Rafelli during their sophomore year, they only intended to record a few seven-inches, and they felt that Rafelli's pop songs would clash with the Electrocutes' tough metal-chick image. Hence the new names: Anderson became Donna A., Robertson Donna R., Castellano Donna C. and Ford Donna F. In interviews, the Electrocutes would even make fun of those "goody-goody Donnas." With two groups, each with identical members but different personalities, the four friends were already mastering that pop-cult maneuver so beloved of Madonna scholars and other cultural critics--playing with female identity. Pictures of the Electrocutes show the girls done up like caricatures of slutty suburban miscreants, all big teased hair, garish lipstick, hot pink lycra and fake leopard skin. With the Donnas, they assumed the guise of the Electrocutes' antecedents, incorporating the styles of bad-ass females from the '50s, '60s and '70s. Their grasp of pop signifiers and music history was almost intuitive, but it wasn't unconscious. These girls knew what they were doing. "The Donnas aren't going to be together for that much longer," Robertson said in a 1997 Palo Alto Weekly story. "But the Electrocutes have bigger and better plans and we all know it." As it turned out, though, audiences responded far more to the Donnas than to the Electrocutes, and so eventually the girls subsumed their first band into the second. The question remains, though: How much are the Donnas self-conscious roles? "I think they used to be more roles than they are now," Anderson says. "Now, I don't feel like I'm playing a role at all. For a while, it was the Donnas and the Electrocutes, but it's not like we chose the Donnas and forgot about the Electrocutes. We merged them together. So now we're more ourselves--in interviews we don't have to say, 'Oh, the Donnas are so lame!' anymore." Castellano chimes in, "When we first started out with the Donnas we were the Electrocutes and we saw the Donnas as a side project, so it seemed like we were taking on characters. Now this is our band--it's us." The first, eponymous Donnas album was a spare, ultracatchy Ramones-style collection of speeded-up '50s-inspired fluff (it even includes a cover of the Crystals' "Da Doo Ron Ron," which was co-written by Phil Spector). Since then, though, the Donnas have been moving toward the bombastic hard rock that inspired the Electrocutes in the first place, paying homage to the hair bands of their youth. Get Skintight owes at least as much to AC/DC as it does to Iggy Pop. Dense and glossy with screeching licks and careening solos, the record isn't punk--it's just rock. Like its predecessors, Get Skintight is animated by pinballing hormones and girlish intensity, but it's the Donnas' mastery of their instruments as much as the defiant brattiness of their lyrics that holds the whole thing together. The music is tough and surging, the guitar and bass dueling arena-style over Castellano's bombastic percussion, Anderson's voice both rough and playful, lusty, not flirty. The music works within the idioms of cock rock, both sonically and lyrically, with only the genders of the "I"s and "you"s reversed. The exception is "You Don't Wanna Call," a '50s-style disappointed-lover's lament cranked up with power-ballad muscularity. "You Don't Wanna Call" indicates that while the Donnas are heavily influenced by metal, they're not abandoning their pop roots, either. "That first Donnas album was not written by us at all," Robertson says. "The person writing the songs was aiming for us to sound very Ramonesy, and we didn't mind that, we liked the Ramones. But when everybody started to compare us to them, it was kind of annoying, because that's not that sound we're always going for. We don't want to be called, like, a Ramones rip-off band. When we started writing and changing Darren's songs on Rock n Roll Machine, you can hear the difference. I tried to put more Kiss and AC/DC influences into my playing. The reason this last album sounds even less like the Ramones is that we wrote it all ourselves." While the sound on Get Skintight is heavier, the lyrics are lighter and more playful than on Rock n Roll Machine (itself not exactly deep). In addition to all the characteristic rock tropes, the Donnas work in some sly references to their middle-class lives in yuppified Palo Alto. Sings Anderson on "You Don't Want to Call," "Am I not old enough, am I too young/You think I don't know how to eat dim sum." Then on "I Didn't Like You Anyway," she disses a loser ex-boyfriend, "I think that nasal spray got to your head/I knew you were lame/from your wallet chain." And on "Party Action," she exults, "You've got the chow mein, and I've got the champagne." It's only since leaving high school, says Robertson, that the Donnas have become comfortable with their essential silliness. "When we first started out, we wanted to be kind of aggressive because we were the only girl band around and other bands made us so insecure. We wanted to be like the riot grrrls, but we didn't really have much to be angry about."

Donna of a New Era: The Donnas have fought hard to overcome industry and media stereotypes that come with being young, female and in an all-girl rock band. Little Cheeba INDEED, AS KIDS, when the would-be musicians in their school ostracized them, the Donnas had gone looking for community among other young women rockers and found, sadly, more indifference. "We thought that since we didn't fit in at our school, we'd fit in with them, and we went to their shows and gave them our tapes and then found them on the ground. They didn't want us," Anderson says. Unlike the riot grrrls, she adds, "we wanted to write about things we liked, so that when we were playing the songs we'd get excited about them. We don't run on rage, we run on fun." Which is interesting, because they were certainly alienated enough to make raging music. Instead of pouring their anger into lyrics, though, they poured it into practice. "Practicing was so much fun. There wasn't really much to do in Palo Alto, so what we'd do is just walk home and practice for hours, and we would talk about what happened at school," Castellano says. "And how everybody at school made fun of us," Robertson adds. "For us, it wasn't about the message, it was about how well you played. I think people were afraid of us because we played better than people wanted us to play. I think they didn't want us to know we were good so they made fun of us and we believed them." The Donnas' revenge, then, wasn't about writing songs that would make people understand the workings of their souls, it was to pour their souls into their instruments. Even after their high school success, all four Donnas had originally intended to go to college. Anderson, Ford and Robertson each spent a semester at UC schools, and Castellano was registered at NYU. Then, the July after graduation, the band signed with the famous East Bay pop-punk label Lookout!, the original home of Green Day. They soon realized that they couldn't give up their very real shot at stardom. Now, as they prepare for an American tour to promote Get Skintight, they're all living with their parents in Palo Alto. In fact, just a few days after returning from a recent tour in England, Castellano spent the day filling in at the health club her parents belong to, handing out towels. That seems strange at first--that these girls who've built their band around rebellion wouldn't be hightailing it out of their childhood homes the second they were able to. In fact, though, all four of them have inordinately good relationships with their parents. And contrary to their image, they were never the kind of girls who got in a lot of trouble. So while they say that songs like "Everybody's Smoking Cheeba" are based on personal experience, the Donnas seem to be more about experimentation than excess. They even recall being appalled by some of the orgiastic antics of their classmates. "Everyone was sleeping around and stuff, and we weren't into that," Anderson says. Ford adds, "These people were having sex contests about how much sex they could have during lunch break, and we were just like, 'We don't want to be part of that.' It was retarded." That attitude explains why the Donnas' mothers are able to remain basically unfazed while hearing their little girls sing about drinking for two and humping all night. "We didn't feel like she was even in danger," says Maya's mother, Marjorie Ford, just a few minutes before the Donnas take the stage at Bimbo's. "I have a son--who's now studying to be a rabbi in Jerusalem--who was very wild. We worried more about him than about Maya." Hyperactive A FEW MOMENTS after Donna dad Baxter Robertson returns to his table near the front of the stage at Bimbo's, the Donnas strut onto the stage in a cascade of pink and violet light and start playing the opening bars of "Another One Bites the Dust." Wearing tight black leather pants and a hot-pink shirt, Anderson shouts, "We're the Donnas! Are you ready to rock & roll?" Then they launch into a propulsive number off the new record, appropriately titled "Hyperactive." There are hundreds in the crowd, lots of older men reliving their hard-rock teenager years but plenty of kids, too, tightly wound boys and fiercely cool girls, and their enthusiasm is genuine. So is the band's. Robertson curls around her guitar, leans into her solos like a '70s rock god, a gesture that seems too joyfully sincere to be obnoxious. With her model-pretty face entirely hidden behind her shiny hair, she looks like Slash from Guns 'N' Roses after a hot-oil treatment. Anderson has one cocky hip thrust toward the audience, and Robertson and Ford back toward her, each forcing wave upon wave of shattering, twisting noise from their guitars. They're utterly in control up there, glowing with new stardom. Occasionally, though, they seem to look at each other quizzically, laughingly, as if to ask, "Can you believe this?" Their sound is big, beaming, hard and rousing. A few women dance furiously in place, sweaty boys bash against each other in the front row and others pogo to see over them. Most of the audience has never heard the songs from Get Skintight before, but they bop through them ecstatically and scream for encores when the set is through. As fans, the Donnas were never able to find a crowd that shared the adulation for celebratory rock anthems, but that crowd is right in front of them now. The audience has adoration in their eyes. The Donnas are leaders of their own pack. [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the June 24-30, 1999 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 1999 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.

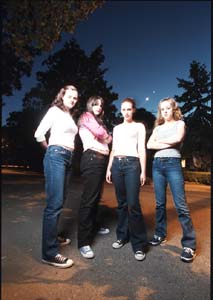

Night Movers: The Donnas rocketed to stardom in high school and put college on hold to devote more time to touring and recording. They've known each other since they were in the eighth grade.

Night Movers: The Donnas rocketed to stardom in high school and put college on hold to devote more time to touring and recording. They've known each other since they were in the eighth grade.