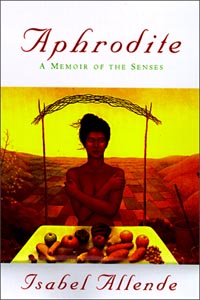

Table of Delights: Martin Maddox's painting 'Morning Grace' graces the cover of Isabel Allende's new book.

Table of Delights: Martin Maddox's painting 'Morning Grace' graces the cover of Isabel Allende's new book.

Aphrodite: A Memoir of the Senses

By Isabel Allende

Harper Collins; 315 pages; $26 cloth

Isabel Allende tastes the pleasures of feast and flesh

By Victor Perera

ISABEL ALLENDE describes her newest work, Aphrodite, as a celebration of the senses--the palate above all--after the rigors of her last book, Paula. In that extraordinary memoir, Allende bore witness to the passage of her grown daughter, who was afflicted with a rare hereditary disease, from a deepening coma to a slow descent into death and rebirth as spirit in her mother's house of spirits.

Allende's yearlong vigil was denied a happy ending, and one can readily understand her desire to reclaim her body by allowing free rein to her lively and omnivorous imagination. Aphrodite is a treatise on aphrodisiacs written ("harvested" might be a better word) with the assistance of her redoubtable mother, Panchita; her world-reknown literary agent, Carmen Balcells; and a cabal of resourceful, globe-trotting friends. Allende revels in the varieties of hedonistic experience with her customary verve and storytelling magic.

In form and content, Aphrodite is as timeless as Ovid's erotic verse, the Kama Sutra and A Thousand and One Nights combined. The book's tone is racy, at times mordant, and as au courant as Diane Ackerman's A Natural History of the Senses or Laura Esquivel's Like Water for Chocolate, to name two probable inspirations.

Allende defines an aphrodisiac as the bridge between gluttony and lust, and there is abundant incitement for both these vices in the pages of Aphrodite. Any food, however bland or repellent, can arouse erotic desire in the partaker and in the object of his or her obsession. The secret lies in the preparation and in the play of the imagination that is brought to the banquet table.

Aphrodite is cobbled together with paradox and contradiction, as all good storytelling is. Allende writes consummately on the ecstacies of a bacchanalia spiced with the right mix of wines and liqueurs--but then admits to "a poor head for alcohol."

She advocates free love as the best cure for melancholy, although she has been a married woman nearly all her adult life; the only break was a three-week period between her divorce and her marriage to her second husband, Willie Gordon, whom she portrays, semifictionalized, in The Infinite Plan. (To judge from the novel, she spent that interval between troths tracking down Gordon and bearding him in his den.)

For all the dizzying array of aphrodisiacs Allende pulls out of her grabbag of edible and poisonous fruits, herbs, mollusks, crustaceans, assorted fungi and a range of fecal or putrescent specialties, she concludes that the imagination is the only infallible instrument of sexual arousal and fulfillment.

Allende remains an acolyte of romantic love, rooted in Rennaissance troubadour traditions. Nothing piques her interest like a honeyed and timely encomium whispered in her ear: "The G-spot is in the ears, and anyone who goofs around looking for it any farther down is wasting his time and ours. Professional lovers ... know that with women the best aphrodisiac is words."

Infinite Planner: Isabel Allende concocts recipes of sensual delight in 'Aphrodite.'

Infinite Planner: Isabel Allende concocts recipes of sensual delight in 'Aphrodite.'

Marcia Lieberman

DURING HER YEARS IN Venezuela, Allende cut her eyeteeth as a columnist for Latin American women's magazines. These lively columns had an edge of audacity that is hard to appreciate fully in English translation, and that holds true for Aphrodite as well, even in the capable hands of Margaret Sayers Peden, Allende's translator. Allende, a self-proclaimed feminist, has puzzled some highbrow reviewers with her premodern notions of love and eros, and with her Latin sexual politics, which do not always conform to North American paradigms. "Feminism has saved me from the traps of imagination," Allende contends, as she leaps headlong into all manner of traps for the sheer satisfaction of clambering out of them with a new tale--or recipe--firmly in her grasp.

Aphrodite opens with well-aimed barbs at the patriarchal "phallocracy" that cornered the market on aphrodisiacs long ago for the exclusive benefit of the testosterone fraternity, while coolly disregarding their female subjects' claim to equal enjoyment. Of course, the masculine obsession with penile fortifiers and enhancers was never confined to Arabian sheiks with vast harems, or to dysfunctional heads of state with diminished or nonexistent libidos.

It's a shame Aphrodite came out too late for Allende to comment on the latest penis-resurrecting wonder drug, Viagra, whose use leaves nothing to the imagination. What does she say of the millions of romantically inert men in our mechanistic age, who are desperate to regain their lost souls under the guise of restored potency? How is a chemically induced, ephemeral erection an improvement, for a savvy and spirited spouse or mistress, over a creatively wielded dildo?

Allende is decidedly postmodern in her reiterated preference for the honeyed or golden tongue over penile penetration. In her garden of earthly delights, cunnilingus rules the roost. She likens the vulva to a fragrant rose or aromatic wine, to a ripe fig or--most appropriately--to an oyster, the ultimate aphrodisiac. The male organ, by contrast, is demoted to a "pathetic" or "shrivelled" pickle, as though sexual liaisons took place in delicatessens.

Of more enduring value than the piquant folk tales and the family anecdotes retold from her earlier books, is the bounty of original and little-known recipes Allende has gathered from every corner of the globe, and from earliest antiquity to the present day. The most outlandish aphrodisiacs are products of hearsay or Asian cuisine, like fugu, the Japanese fish that is so toxic only a master chef can clean and prepare it properly to assure the desired effect without condemning its consumer to a gruesome and shortlived ecstacy.

The choicest of all are Allende's and her Basque mother's South American recipes. Nothing is left to chance in Panchita's impeccable chupe, or chowder, made with sea urchins and well-pounded Chilean abalone, called locos.

Even more enticing is her Chilean curanto, inspired by the Polynesian stew of remote Easter Island that is concocted from various meats and sausages, fishes, mollusks and crustaceans, potatoes and corncobs cooked in an earthen pit overlaid with banana leaves. Perusing Panchita's recipe for her domestic curanto de olla brought back the haunted woods, leaden skies and secret withcraft of another Chilean island, Chiloe, off the shores of Patagonia.

One dark, rainy evening a heavy-browed, thick-waisted curandera rid me of a chill with a peasant curanto that has stuck as durably to my memory as it predictably did to my ribs. Lying in bed late that night, under layers of quilts and ponchos, my dreams abounded in wild trysts with she-goblins, tree-nymphs and fanciful sea-monsters that found fertile soil in my fevered imagination, and never let go.

Victor Perera is the author of The Cross and the Pear Tree: A Sephardic Journey. He is currently translating the narratives of the Kogi Indians of northern Colombia, and completing a book on whales for Alfred A. Knopf.

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![[Metroactive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)