The Lawn Good-bye

Sensitive gardener meets sensitive little girl; some insensitive people intervene

A VIEWER CAN get the wrong impression from Lawn Dogs. Screenwriter Naomi Wallace has created alternately tough and callow dialogue that suggests a novice film-school grad's work. Director John Duigan, who has made the film with more sensitivity than sensibility, goes along with Wallace's conceit.

Both, however, are veterans. Wallace is a noted playwright; Duigan, an Australian, has made an even dozen movies, including Romero (1989), about the martyred archbishop; Flirting (1990); and his lofty cheesecake hit Sirens (1994).

Lawn Dogs takes on two tricky issues. One of these is the most danger-prone relationship imaginable: the friendship of a single man and a little girl. In America, our little girls are exceptionally pristine, and our single men are exceptionally suspicious. There is no quicker path to destruction than to have such a friendship misunderstood--murder is less grave. The narrative problem with such a friendship is that this danger is common knowledge. How dumb can Trent (Sam Rockwell) be not to realize that peril?

Trent, who's in his early 20s, works a power mower in a walled-off minimansion development called Camelot Gardens. (The film was shot among the golf-course farms outside Louisville, Ky.) Brick gateposts rise out of a field to ward away strangers; an armed security guard named Nash (Bruce McGill), believing himself to be the sheriff, leans on outsiders.

Ten-year-old Devon (Mischa Barton) takes an interest in the gardener initially because of her isolation from her socially striving father (Christopher McDonald) and straying mother (Kathleen Quinlan). The gardener and the girl are linked by a brush with death: Trent was shot by the police years before, and Devon has had two operations for heart problems.

Trent lives in a trailer in the woods that Devon discovers. She keeps turning up on the man's porch, and a friendship ensues. Before long, Devon's parents, Nash and a couple of local bullies (David Barry Gray and Eric Mabius)--one of them, inevitably, a genuine child molester--all descend on the two like a ton of bricks.

An impressive spot of digital magic marks the end of the film, and some of Wallace's lines have the dry, stinging quality of New Yorker cartoon punch lines. (Nouveau riche mom, bringing a salad bowl to the table: "Le salad, c'est arrive.") Wit aside, the pitch and mood are artificial. Devon says that her fellow kids "smell of television"; Lawn Dogs smells of playwriting.

I said Lawn Dogs was about two tricky subjects. The second is probably even more prickly than child/adult love. I'm speaking of class. Duigan lays the class differences on thickly, as only a non-American would. He doesn't realize the mix of signals, the embarrassment, the mutability that are all a part of the difference between the lower and upper classes in this country.

Duigan doesn't seem to realize how quickly the tables can be turned--how in America, a truck driver can shame a professor for his elitism. By making Trent completely persecuted (the bullies even have a police dog), he adds to an atmosphere of dread; watching Lawn Dogs is like waiting for a collision that everybody knows is coming.

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![]()

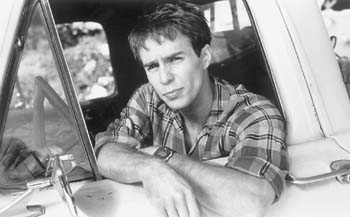

Lawnmower Man: Trailer-dwelling loner Trent (Sam Rockwell) drives straight into trouble when he befriends a young girl in 'Lawn Dogs.'

Lawn Dogs (Unrated; 101 min.), directed by John Duigan, written by Naomi Wallace, photographed by Elliot Davis and starring Mischa Barton and Sam Rockwell.

From the June 25-July 1, 1998 issue of Metro.

![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)