Monkeying Around

Virginia Woolf's pet marmoset finally receives a roomy biography of its own

By Tai Moses

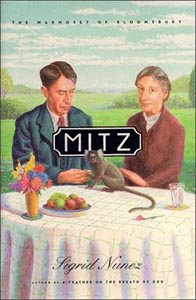

HAS EVEN a particle of history about Bloomsbury, the legendary London literary clique, gone unexamined? With the publication of novelist Sigrid Nunez's droll new book, the answer is no. Thanks to Nunez, even Bloomsbury's tiniest resident has her own biography. The pet marmoset who belonged to Virginia Woolf's husband, Leonard, is the subject of Mitz: The Marmoset of Bloomsbury.

A marmoset is a tiny arboreal monkey scarcely larger than a baby squirrel, native to the rainforests of South America. Such a creature would be miserably out of place in dreary drizzly England, and apparently that was Leonard Woolf's impression when he first saw Mitz, suffering from rickets and mange, come limping across the Rothschilds' fabulous lawn at tea one day in 1934.

Quentin Bell, Virginia Woolf's nephew and later her biographer, loathed Mitz, claiming that her face resembled Joseph Goebbels' (as Bell noted in his 1996 memoir, Bloomsbury Recalled). The marmoset, wrote Bell with uncharacteristic venom, "seemed to be in a perpetual state of vicious fury; ugly at all times, it became hideous when it vented its spite at the world. It was deeply in love with Leonard and would spit out its jealousy upon the rest of humanity."

Nunez's portrait of Mitz is far more forgiving--Mitz looked nothing like a Nazi but was merely clownish and elfin, like most marmosets. She was certainly passionate about Leonard Woolf, who, after all, had saved her from a wretched existence. But the animal's charms were lost on most of Leonard and Virginia's friends and family members. Virginia's sister, Vanessa Bell, referred to her as "that horrid little monkey," and the only person who seems really to have liked Mitz was Lady Ottoline Morrell, one of Bloomsbury's great party throwers.

The author has combed through voluminous heaps of Bloomsbury lore, the countless biographies, memoirs, diaries and letter collections (Virginia Woolf left nearly 4,000 letters and a 30-volume diary) and culled her facts and quotations carefully, adding invented conversation and shaping her book with a jeweler's eye for precision. There is not much in this slender volume that is new, but the novelist's approach provides a charming, if circumscribed, window into the Woolf household.

Virginia Woolf's own book Flush: A Biography (1933)--a waggish reconstruction of the life and times of Elizabeth Barrett Browning's pet spaniel--was obviously Nunez's inspiration. While Flush was neither a critical nor a popular success, Virginia's friend and occasional gadfly E.M. Forster called it "doggie without being silly" and praised the book for furnishing "a peep at high poetic personages and a new angle on their ways."

FORSTER'S APPRAISAL could just about sum up Mitz, which is considerably less a book about a marmoset than it is a portrait of one of literature's most celebrated creative and domestic partnerships. Virginia Woolf considered pets to be symbols of the "private side of life--the play side." Play is in abundance here, but always balanced by work, the Woolfs' passion.

This is Bloomsbury's twilight era: Lytton Strachey is dead, Virginia's beloved nephew Julian Bell will soon go off to die in Spain and the foremost topic on peoples' minds is the growing threat of war in Europe. Meanwhile, Virginia is feverishly at work on her tempest of a book, The Years.

The Woolfs' domestic and social life comes into sharp focus, images unfolding like an accordion string of postcards: Mitz unties T.S. Eliot's shoelaces; Vita Sackville-West sends a Christmas pie; Leonard and Virginia relax in the garden of their Sussex cottage. After being served breakfast in bed by Leonard, Virginia goes to work in her studio, sitting in a cozy armchair with a plywood board over her knees for a desk.

In this vein, the Woolfs soon begin to resemble a frumpy, eccentric aunt and uncle. One pictures Leonard's clothes covered with dog hair, the corners of the couple's London flat smelling suspiciously of Mitz (marmosets are notoriously odoriferous).

Mitz is most useful not for the events it depicts--most of this information can be gleaned from other sources--but for what the distillation of Mitz's story tells us about the Woolfs themselves. It speaks well for the stability of the Woolf household that a fragile tropical creature like a marmoset could thrive there for more than four years. Leonard seems to have treated the tiny monkey with the same solicitude he lavished upon his wife. As the only resident male, he often addressed the other members of his household--wife, spaniel, marmoset and maid--as "the ladies."

THERE ARE NO monkeys in either of Nunez's two previous books: the autobiographical novel A Feather on the Breath of God and the psychological drama Naked Sleeper, and the narrative style Nunez has adopted for Mitz--its prose so relaxed as to resemble a children's book at times--alternately beguiles and annoys. Perhaps Nunez took on her whimsical role as a marmoset's biographer as a relief from novel writing, just as Woolf herself undertook Flush as, according to Nunez, "something to cool a brain that had seethed and bubbled over during the feverish labor of completing The Waves."

But what, I found myself wondering, does that marmoset represent? "Cats and monkeys, monkeys and cats--all human life is there," Nunez quotes Henry James. I began to see Mitz as Virginia's muse incarnate: an intractable presence, capable of both succor and torment, alternating between wild chatter or baleful watchfulness.

Author and marmoset were, Nunez observes, "two nervous, delicate, wary females, one as relentlessly curious as the other." In her diary, Virginia wrote that Mitz behaved "as if the world were a question." In contemplation of this tiny animal, as dependent upon Leonard as she herself was, Virginia seems to have found a reflection of her own nature.

This is not as strange as it sounds. Virginia's own pet names were monkey derived: her childhood nickname was Apes; Vanessa called her Singe, French for monkey; and Leonard's name for her was Mandril (she called him Mongoose). What it all suggests is that, in addition to their valuable artistic, literary and intellectual contributions--the denizens of the small London neighborhood that was Bloomsbury also found time--thank goodness--for a bit of innocent monkeying around.

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Marmoset See, Marmoset Do: There was more to Bloomsbury than literary witticisms.

Marmoset See, Marmoset Do: There was more to Bloomsbury than literary witticisms.

Mitz: The Marmoset of Bloomsbury

By Sigrid Nunez

HarperFlamingo; 116 pages; $18 cloth

From the June 25-July 1, 1998 issue of Metro.

![[Metroactive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)