![[Metroactive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

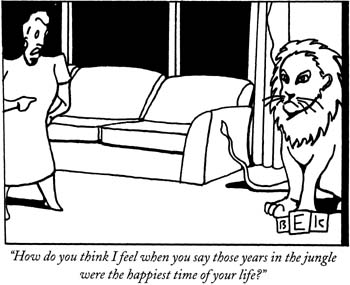

Cartoon Neurotics

The characters in Bruce Eric Kaplan's panels always blame themselves REMEMBER "The Cartoon" episode of Seinfeld? Elaine is chafing about her dashed hopes in life ("I don't know what it is I wanted to be--anything but this"). Once, it seems, Elaine nursed an ambition to become a cartoonist. So she pulls an all-nighter to produce a drawing of a pig at the complaints window of a department store, saying, "I wish I were taller." The cartoon finds acceptance in The New Yorker. Unfortunately, Elaine's victory over oblivion is only temporary. Turns out she unconsciously plagiarized her caption from Tom Wilson's hideous daily cartoon, Ziggy. Jerry Seinfeld's own alternative caption for the drawing--"My room is a sty"--gets a bigger laugh from the studio audience. But Elaine's caption is much closer to that understated, genteel quality of the classic New Yorker cartoon. How to sum up that spirit? Essentially, a wistful pig is a little more profound than a tummeling pig. The writer of that episode, Bruce Eric Kaplan, is in fact a cartoonist at The New Yorker. Kaplan uses the monogram "BEK" as his signature. Along with stalwarts like Roz Chast and the illustrator Bruce McCall, Kaplan really honors the magazine's tradition of hosting the best panel cartoons in the world. Kaplan's first book, No One You Know ($13.95; Simon and Schuster), collects 182 of his cartoons. It's treacherous trying to describe these cartoons as anything other than "really funny." Panel cartoons are balloons, and you can burst them trying to get inside. Kaplan captures a great deal of neurotic energy in a few short strokes of the pen. In his gracious introduction to the book, playwright Neil Simon observes that Kaplan doesn't ever seem to lift his pen off the paper. True, there is an Etch-a-Sketch style to Kaplan's drawings. The cartoonist's work always stands out from the page thanks to its angles and sharpness. And there isn't anything playful about the pictures. The backgrounds are fierce, rude squares within the square: perhaps blood-freezing minimalist paintings, perhaps the windows of crucifyingly chic department stores. The characters are foreshortened, about the right size to loom over a lapdog. Kaplan's hollow-eyed denizens lean forward or are pitched back in the beginnings of a melodramatic swoon. They're always weak at the knees over their hurts. Their left hands, splayed like starfish, are open stiffly, plainly showing how wound-up they are. Caught in mid-tirade, Kaplan's people are the only moving things in their big empty rooms. George Booth, Kaplan's fellow cartoonist, captures perfectly the archetypal poor-person apartment, with its ironing board in the kitchen, its homely mutt poised to start chewing on its fleas, its perilous octopus of electrical wires sprouting out of the overhead socket. Kaplan is just as good at nailing the intimidating spaciousness of the well-bred upper-middle-class flat. Kaplan's dogs, cats and children--the other tenants of these large flats--are just as rife with angst as the adults. A stifled house cat: "Maybe I could have done more with myself if I hadn't been so focused on tearing up the sofa." One dog to another: "Pee on the carpet!' That's your solution to everything!" A pleading little girl to her brother: "You're using the bogeyman as an excuse to shut me out." Even a shark has creases under its eyes, so desperate is it not to be misunderstood. The shark, on the defensive, pleads with a woman at a cocktail party: Yes, of course he loved Schindler's List, but he still thinks Jaws was better. IF NONE of these cartoons have struck you as funny--then, like one of Kaplan's characters, I blame myself. Kaplan's predecessor at The New Yorker, James Thurber, has that same inexplicable quality. Personally, I laugh every time I think of Thurber's caption for a drawing of a miffed woman at a picture window: "Then don't come and look at the pretty sunset, you big ape!" Like Elaine explaining her cartoon pig, I might have to explain that what's funny in the Thurber isn't the unseen husband's gruffness but the wife's thin pretense of aestheticism. And if that kind of explanation can't kill a joke, nothing can! One last example: a Kaplan cartoon shows a (hollow-eyed) fish telling another fish, "I'd appreciate it if you talked to me without staring at my gills." The preface, "I'd appreciate it ... ," to the fish's request is what makes it funny. Kaplan's work is about the diabolism of the civilized. His neurotic characters, just like the Seinfeld gang, nurse their infinitesimal hurts but pretend that they're not great big babies. As regular viewers know, Seinfeld and friends are at their most hilariously mean when they're trying to be evolved and sensitive. Kaplan's terrific cartoons show inside knowledge of faux-sensitivity. No cartoonist today rivals his ability to observe faux-politeness; no one else is as good at caricaturing that smarm that coats so much emotional and business thuggery. [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the July 1-7, 1999 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 1999 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.