![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Family Feud

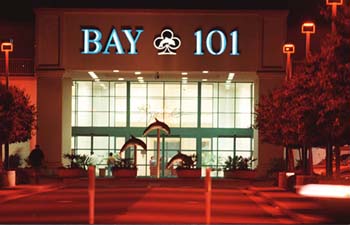

Christopher Gardner Split Personality: The Bumb family made millions off of the San Jose Flea Market (below), started by George Bumb Sr. in 1960, and bolstered its financial fortunes with the opening of Bay 101 in 1994, a project started by now-outcast son Jeff Bumb.

The Bumbs made millions off of their successful gaming club, Bay 101, but the experience tore the family apart and aired the dirty laundry of a once tightly-knit and fiercely private clan. By Will Harper FROM THE protected confines of his silver 1998 Lexus SC 400, Jeff Bumb peers out his window to take in the imposing sight of the 72,000-square-foot salmon-hued house of cards he once called his baby. "I did a great job," Bumb says of the sprawling gambling club, furiously chomping on a piece of Wrigley's Doublemint, the gum he chews when he's not sucking on an unfiltered Camel. The air conditioning is on, but beads of sweat surface on Bumb's forehead, between a pair of fierce-looking blue eyes and a receding blonde hairline. A blue knit polo shirt covers his stocky 52-year-old frame. Bay 101 was Jeff's idea--no one disputes that. Even in the tangle of legal briefs and heated accusations, no one denies that Jeff is the one who hunted down a site, negotiated the deal and spent hours on the phone lobbying San Jose City Council members for a big, new gaming house in San Jose. He babysat the construction site every day for almost five months. On weekends he'd bring his wife and a few of his 10 kids down there, too. The dolphin fountain at the front entrance is there because he wanted it there--water and fish are good luck. He chose the building's peachy-pink paint job, he says, because he wanted "a pleasant, welcoming earth tone." As we do our drive-by on a Tuesday midmorning, there are more than 100 cars in the parking lot. The day before, Monday at noon, half of the club's tables were full of gamblers playing seven card stud, Omaha and Texas Hold 'Em. "It's making a whole lot of money," Bumb says of the club which city financial forecasters have predicted will gross $34.6 million this year, $11.5 million more than its cross-town rival, Garden City. But Jeff Bumb hasn't made a penny from the club since it opened in September 1994. `He drives by every day on his way to his Maverick Consulting development business in Mountain View, but he never gets off the Brokaw/First Street exit to pay a visit. In fact, he hasn't set foot in the place since October 1995, the year he stopped talking to his father and three brothers. But Jeff Bumb would greatly prefer not to talk about this. The only reason we are driving around in his Lexus today is because he knows I have read the bizarre and bitter contents of a 2-foot-high stack of documents down at the Santa Clara County Superior Courthouse. He can't ignore it. In the last five years, the Bumb family and its enterprises have been investigated for illegal political campaign contributions, an alleged profit-skimming racket out at the Berryessa Flea Market and even a murder-for-hire scheme involving Johnny Venzon, a former cop, convicted thief and gambling addict. Jeff himself was hit with a federal grand jury investigation over financial transactions in connection with a multimillion-dollar residential development near Silver Creek Road. If all this weren't enough, a sexual relationship between his 14-year-old daughter and a 19-year-old Bumb cousin was reported to police, slicing the family's cherished privacy wide open for the world to see. Ultimately, Jeff says with resignation, he hopes I find the truth, "not my truth, not their truth, just the truth." THINGS WERE certainly simpler back in the old days, before Bay 101, when the Bumbs were known for the Berryessa Flea Market, the family-owned business started in 1960 by 75-year-old family patriarch George Bumb Sr. The Flea Market, touted as the nation's largest, made the Bumbs rich, grossing nearly $12 million in 1996. Today, Bumb family enterprises include the local Premium Pet Stores chain, Air One Helicopters and, of course, Bay 101. The Bumbs' reputation as an unconventional, insular, wealthy, large brood keeps tongues in political circles flapping. One wag refers to them as "the Beverly Hillbillies of San Jose." Their pun-afflicted surname adds to the hillbilly mystique. Jeff Bumb remembers that when he was going to school at Bellarmine in the '60s, the other kids would call him things like "Bumbsy" or "Bumbo." Jeff didn't mind, though. "I liked my name," he maintains. "It made you tough, made you get a thick skin." Three years ago, the Mercury News listed the Bumb family in the Top 10 of the valley's most generous political contributors. Campaign records show that Bumb & Associates and Bay 101 have made at least $587,000 in campaign donations since 1994 to local and state politicians and ballot measures. Over the past year alone, Bumb & Associates and Bay 101 have given $56,000 to now-Attorney General Bill Lockyer, the man in charge of card-room regulation. But the Bumbs are hardly traditional political players. When family patriarch and Flea Market mastermind George Bumb Sr. was invited to attend a party with President Clinton in San Francisco a couple of years ago, he refused to go and sent his community relations specialist, Betsy Bryant, instead. When Vice President Al Gore called to personally invite the elder Bumb to a fundraiser at the Los Altos home of real estate magnate George Marcus, Bumb put the VP on hold for several minutes, ultimately making Betsy take the call. "What am I going to say to the vice president?" he asked. Seven of George Bumb Sr.'s eight grown children reside in the eastside foothills within a mile or two of their father, often on the same block. Most of George Bumb Sr.'s five dozen grandchildren have grown up in the 95127 ZIP code and have attended the family-run K-12 Catholic school, St. Thomas More, located on Flea Market grounds since 1978. (Tim Bumb, the school's director, says it was put there to save on rent. About 20 percent of the 130 students there are Bumb relatives.) When the Vatican eliminated Latin from the Catholic mass in the '60s, George Bumb Sr. responded by building his own chapel, named for the rebellious St. Athanasius, at the base of Mt. Hamilton, where Latin mass is conducted on a regular basis. For all his quirks and controlling behavior, the old man is regarded as a benefactor by most family members and some Flea Market employees who know their boss to be capable of great generosity. As legend has it, the Bumbs still send a monthly check to the widow of a former head of security who died of a brain tumor 20 years ago. Bryant, who acts as emissary for the family and its patriarch, thinks the Bumbs are a misunderstood bunch. In her 10 years as the Flea Market's community relations specialist, Bryant has come to adore the lack of pretension among this clan of millionaires who have their offices in a mobile home where none of the furniture seems to match. "It's a very strong family. It's very tightknit," says Bryant, adding that the senior Bumb doesn't give interviews--ever. "The thing they probably value most is their privacy," Bryant explains. Privacy hasn't been so easy to come by for the Bumbs in the '90s, since they got involved in Bay 101. The card club has done more than bring unwanted public scrutiny to this insular group. It did the unthinkable: It pitted Bumb against Bumb.

Life of Brian: Initially denied a gaming license by the state, Brian Bumb has since received a provisional license and become a partner in Bay 101 with his brothers, Tim and George. He also runs day-to-day operations at the family-owned Flea Market. FROM THE START, Jeff's three brothers and father didn't share his enthusiasm for opening a lavish gaming house. It wasn't the idea of gambling. Jeff's grandfather, Frank Bumb, had met his wife, Mary, at a card parlor in San Francisco where they worked. George Bumb Sr., an avid card player, held a regular weekly family poker game at his home. And Jeff himself had been playing poker since he was 12. It wasn't the money, either. The Bumbs had a plenty of experience with a cash business through the Flea Market, which they've run for almost 40 years. Tim, the second youngest of George Bumb's four boys, was already running the family toy business, Fact Games, and Premium Pet Stores. George Bumb Jr., the quiet one with a flair for things mechanical, was already at the controls of Air One Helicopter. And Brian, the handsome and gregarious youngest brother, was in charge of day-to-day operations at the Flea Market. The gambling palace Jeff Bumb--the oldest son who is often described as the most entrepreneurial of the four brothers--had in mind was going to take a lot of effort and political skill. He wanted to relocate and expand Sutter's Place in Alviso from a five-table card room to a 40-table one, matching the size of Northern California's largest card room, Garden City in San Jose. That promised to be a hard sell to the San Jose City Council, which would have to authorize both the new site and the expansion. But Jeff was confident. Over the years, he had developed working relationships with the city's politicians and bureaucrats. Whenever trouble arose at the Flea Market with city code or building inspectors, the Bumbs sent Jeff to settle things. "Jeff is a wheeler and dealer," explained his Uncle John, the Flea Market's executive vice president and owner of the Skeeball Arcade. "He took care of it." At the time, San Jose, like cities throughout the state, was strapped for cash, looking at an $11 million budget shortfall. Realizing that, Jeff offered to pay higher card-room taxes (next year the city expects to collect $4.5 million from Bay 101) and pick up the tab for security. On March 17, 1993, the City Council gave Bumb and his partners the green light to open a 40-table card room on a 10-acre plot of land off U.S 101. But his dream, which now seemed so close to being a reality, was about to become a nightmare. EIGHT MONTHS AFTER its approval by the City Council, the peach-colored Bay 101 held its "grand opening." There were flowers everywhere. And there were gamblers everywhere who had come looking for some action. Dealers stood at the tables, ready to deal the cards. But there was no gambling done that night. The state, still busy conducting background checks, still hadn't approved the Bumbs and their partners' gaming licenses. One month later, the state attorney general's office made a devastating announcement: Authorities had come across issues of "such magnitude" and "concern" that they would need at least another month to decide if gambling should be allowed at Bay 101. The ensuing delay forced Jeff Bumb to lay off 600 workers he had hired. Behind the scenes, the Bumbs suspected their potential gambling competitors and a disgruntled former Flea Market employee of giving investigators unsubstantiated material to use against them. Some improprieties did turn up: Bumb & Associates, a partnership including the four brothers and their father, had failed to file required reports disclosing more than $100,000 in political contributions made between 1989 and 1992. Jeff Bumb later explained to the press that they didn't know partnerships were required to file such reports, and they paid the state a $1,250 fine. Other allegations were more dubious: Investigators chased after a tip that the Bumbs were skimming cash from the Flea Market parking lot, an accusation that was never proven. And then there's the stuff that never made it into headlines, like the alleged murder-for-hire plot out at the Flea Market. Jeff Bumb says he believes that state and local investigators at the time of Bay 101's limbo were investigating a rumor that Jeff had tried to get someone killed, a charge Jeff denies. The investigation was given a shot in the arm after the arrest of Johnny Venzon in 1997, a cop who made headlines for burglarizing homes while on duty to pay for his mounting gambling debts. His crimes included taking valuables from the bereaved family members of dead crime victims while pretending to console them. He also pulled off an armed robbery of the Aloha Roller Palace. During the Venzon investigation, San Jose police dug up an old file from November 1990 in which Venzon, a sheriff's deputy, had reported his department-issued Smith & Wesson 9 mm automatic stolen. Eight months later, the frame of the weapon was found in a Salinas pond near Venzon's home with the barrel and slide missing. Deputy chief Tom Wheatley says that police wondered if Venzon, or someone, destroyed the barrel to prevent a ballistics test from tracing a fired bullet to the gun. And then police remembered the old rumors about a murder plot at the Flea Market, where Venzon had worked as a security guard for more than 15 years.

Snow White or Cinderella? When Jeff and Brian were denied licenses for Bay 101, Tim (above) and brother George Jr. jumped in. Tim now runs Bay 101, which he says is no easy task. VENZON WAS well known to the Bumbs. In fact, on the day he was arrested, records show that Venzon pawned a 14-karat-gold diamond cluster ring and a ladies' gold tennis bracelet for a total of $298 at American Precious Metals, a jewelry store at the Flea Market run by Joseph Bumb. During his long tenure at the Flea Market, Venzon apparently developed a close relationship with George Bumb Sr. When he was jailed, the desperate cop wrote a 15-page handwritten letter in pencil to George Bumb in May 1997 asking the Flea Market owner to bail him out. "And when I visited you at your home I told you that other than God you are the only person I've gotten down on my knees for," Venzon says on page 7. "And I told you that I loved you and you are like a father to me. Well, George, whether you want to believe it or not I do love you and you are like a father to me." Near the end Venzon writes, "They want to bring up the 'murder-for-hire' investigation again. (That thing that involved Jeff when Bay 101 was scheduled to open but didn't.)" The district attorney's office says that Bumb attorney Ron Werner turned the letter over to authorities immediately after it came in the mail. Earlier this year, a month before Venzon was sentenced to 14 years in prison, district attorney investigator Michael Schembri closed out the Venzon case, noting in a court filing, "No new information has been uncovered relating to the murder for hire case [at the Flea Market] which our department investigated several years ago." Though authorities were never able to prove a paid snuff plot, Jeff Bumb believes the allegations were a factor contributing to authorities' mistrust of him. In February 1994, nearly one year after the San Jose City Council gave Bay 101 its blessing, the state denied the Bumbs and their partners' gaming license application. EVERY DAY THE CLUB stayed closed, the Bumbs lost more money. Now that their gaming license had been denied, a decision needed to be made--quickly. Jeff entertained offers to buy the club, the highest bid, he recalls, coming in at $40 million. But he didn't cash out. Or at least he thought he didn't. He and his brothers had a plan, he says. Tim and George Jr. would appeal and reapply, the hope being that the club would open as soon as possible. Of the four brothers, Tim and George had faced the least resistance from state gaming officials. "They had to find Snow White and Cinderella," Tim Bumb says, "and that was George and I." So Jeff, Brian and the remaining non-family partners backed out of Bay 101, handing everything over to Tim and George Jr. Jeff signed a deal with his brothers that prohibited him from owning Bay 101 stock until he got all the necessary licenses. Unlike other partners, neither Jeff nor Brian had buyback provisions in their written agreements, an intentional omission meant to appease state gaming officials who wanted them out of the picture. Just so everyone got the point, Jeff Bumb announced to the press that he and Brian were divesting from Bay 101, and records show he eventually sold his shares for $1.4 million. Finally, in July 1994, the state cleared Tim and George and gave them a conditional OK to let the games begin. But Jeff says that privately he and his brothers had an oral agreement--which Tim Bumb now corroborates--that would one day let him repurchase his shares and become a partner in Bay 101 again.

Preventive Medicine: George Bumb Jr. is a co-owner of Bay 101, where a snakebite kit is kept on-hand as a family joke. ON AUG. 11, 1995, Jeff sat in his Flea Market office scribbling on a piece of paper, plotting his grand return to his peach palace. As a compromise of sorts, he was debating whether he should apply for a license as a gaming-club manager instead of as an owner. He asked longtime family attorney Ron Werner if his brothers could write a recommendation letter for him, something state officials had told him he would need to be considered eligible for a gaming license. Werner said no. Tim and George Jr. worried that pressuring state and city officials to deal Jeff back in at Bay 101 would backfire and authorities would close down the card room. Tim and George, under pressure from then Police Chief Lou Cobarruviaz, had already signed an agreement a year earlier that prohibited Brian, Jeff and their father from having anything to do with the card room. In fact, Tim and George had to agree not to collaborate with other Bumbs on any new business venture. Tim Bumb says writing a letter on Jeff's behalf would have violated the agreement with the police chief and put the club in jeopardy. He also disputes that such a letter was even necessary for Jeff to get licensed. "We made it very clear to Jeff and everybody else concerned," Tim says, "that I'm not going to stick my neck on the line here. ... And it was very explicit in there that no Bumbs could have anything to do with the club. And he [Jeff] wants me to violate the condition which says in it that I sign away my rights and they close us down. Well, guess what? I'm on the hook for $15 million. And that ain't happening because I can't afford it." When Werner broke the news that Jeff's brothers wouldn't write a letter on his behalf, he says Jeff became furious. In a fit, he took the paper he was writing on, crumpled it up and threw it out the office door. "I don't need their help," he barked at Werner. "I'm a big boy." He started telling people around the office that he wanted out of the family business. And then, just when it seemed as though family relations couldn't get any worse, they did. A FEW DAYS AFTER returning from his son's Oct. 13, 1995, military graduation in San Diego, Jeff and his wife, Elizabeth, got some appalling news: Their 14-year-old daughter had been involved in a sexual relationship with an older male cousin. Police reports would suggest she had, "for about a year," been giving "blow jobs" to 19-year-old Matthew Bumb, son of George Bumb Jr. Matthew is the kind of guy a relative described to police as "polite," the guy parents wanted their daughters to date. He was also the kind of guy, police records reveal, who told his mother about the incidents "because he felt guilty." Soon after his confession, the word started spreading in the family about what happened. In a statement to police, Jeff's daughter recounted how the first incident had happened the year before on the Fourth of July at a family beach house near Santa Cruz when the older boy allegedly started fondling her while she was asleep on the living room couch. The teenagers had been drinking booze earlier in the night.

Christopher Gardner

She recalled that she was dressed in shorts and a T-shirt covered by a blanket. Even though all the lights were out, she told police that she knew it was Matthew "because the moonlight shined into the room through the large windows that faced the ocean." She told police about at least seven other sexual encounters she had with her cousin after that. The two, she said, never talked about what was going on while it was happening. After learning of the incident, Jeff and wife Elizabeth did not report the matter to police immediately. According to Jeff, there was tremendous pressure from his father and others in the family to keep the incest a secret. And for nearly a month, they did. But Jeff and his family started hearing that instead of showing concern and support for his daughter, George Bumb Sr. and others in the family were blaming his freshman daughter for the incident and not her adult-age cousin. One of George Bumb Sr.'s granddaughters explained to police that her family was very old-fashioned: "The woman gets the short end of the deal; she is a whore. The guy doesn't get a slap on the hand." Jeff was also getting word from his nieces and nephews that his father said at a family poker game: "If it was up to him, all the grandchildren would marry each other." On Nov. 8, 1995, attorney Albin Danell, Elizabeth's brother-in-law, contacted the police, apparently after consulting with Elizabeth. "I mean," Jeff later said at a deposition, "it was a time of hurt and heartache for us--and not my father, not my mother, not my brother George, not my brother Tim, not Brian could care less." At one point in the investigation, sheriff's detectives had Jeff's daughter call Matthew while he was working at the Flea Market to confirm the sexual activities. They recorded the conversation. Toward the end of the call, things got heated. Jeff's daughter interrupted Matthew and said, "And I didn't know better. You know the school we went to?" she said, referring to the family-run Catholic school at the Flea Market. "They didn't teach anything about this. OK--we didn't get out--OK? It's like we had no life except for the family." Initially, police filed felony charges against Matthew Bumb for having oral sex with a minor and penetrating her with his fingers. Ultimately, the charges against the older Bumb were reduced to a misdemeanor. Matthew Bumb's attorney argued that the relationship was consensual. Bumb family attorney Ron Werner suggested that Jeff and his family had a hidden motive for waiting nearly a month to report the incident to police. At the time, Jeff was in the midst of negotiating an arrangement to be bought out of the family businesses. According to Werner, molestation of his daughter became part of a laundry list of damning things Jeff threatened to disclose if his buy-out demands weren't met. Jeff tells the story differently: "Matthew was my godson. You think this didn't break my heart?" Eight days after the molestation incident was reported to police--and one day after Jeff Bumb formally refused his father's $6.9 million buyout offer--George Bumb Sr. sent Jeff a curt typewritten memo informing Jeff that he was terminated effective immediately and had to clean out his desk before 5pm. Before the end of the month, the Flea Market laid off Jeff's daughters Anne and Rebecca. Within weeks, Jeff says, his six-month-old dog was dead, his cat was dead and the tires of a family car were slashed. "My wife broke the code," he says, "and I supported her." ALL TOGETHER, the intrafamily litigation has spanned nearly three years. First, Jeff tried to have the Bumb & Associates partnership dissolved after accusing his family of trying to force him out without paying him a fair price. He followed that with suits alleging breach of contract, wrongful termination and misrepresentation. He demanded $10 million from his brothers to compensate him for violating the purported secret Bay 101 deal. Along the way, Jeff raised the ante, hiring Frank Ubhaus, a lawyer who represented Garden City card club, Bay 101's crosstown rival. In response to Jeff's legal attacks, George Bumb Sr. and Bumb & Associates filed two separate suits of their own to collect nearly $1 million in loans and interest they claimed Jeff never paid. (In one case, George Bumb Sr. loaned Jeff $31,250 in 1992 for his son to invest in Bay 101.) The court saga evolved into a battle of wills between a father--a man who wouldn't even let the Vatican tell him what to do--and his oldest son, determined to break free from the old man's grasp. George Bumb Sr.'s loan-repayment demands came in July 1996, just as his oldest son and his wife were about to move to Los Gatos and break away from the family and its eastside enclave. The couple even had a purchase contract for a $850,000 house on Golf Links Road. But Jeff says the loan dispute screwed up their moving plans. "My issue with [George Bumb Sr.]," Jeff Bumb complains about his father, "was his control of where you lived, what kind of house you bought, where your children went to school, ... who your friends are, ... whether your children went to college, who they would marry, what kind of wedding they would have." Meanwhile, Jeff and his lawyers spent 15 months trying get his father to appear at a deposition. Originally he was scheduled for questioning on March 10, 1997, but the old man's lawyers explained that their client was extremely ill, suffering from "severe life-threatening conditions," practically on his death bed. Almost four months later, on July 21, 1998, George Bumb Sr. appeared in the downtown offices of Berliner Cohen to have his deposition taken. A nurse was present to monitor his condition. The elder Bumb may not have been feeling well, but he wasn't too sick to remember who was boss in this family. "Could he [Jeff] do any other work on his own behalf?" attorney Frank Ubhaus asked the Bumb patriarch. "Hell, no," George Bumb replied. "He worked for me."

AN ATTORNEY involved likened the whole contentious affair to a divorce. And as with any divorce, embarrassing private details about the family and its businesses made their way into the public record. Jeff portrayed his father as a control freak who ruled through fear and intimidation. "At all times the family has been under the control and domination of George Bumb Sr.," Jeff tore into his father in one of his countless affidavits. Upon questioning by Jeff's lawyer, John Bumb acknowledged that his brother George Bumb Sr. threw a fit at three of his children's weddings because they played rock & roll. "He didn't like the music," John recalled, "so he would make a mess." Jeff also brought up the time when his brother Brian, as a grown man, had been fired by George Bumb Sr. from the Flea Market for showing up to work in sneakers. And with some lawyerly prodding, Dan Carlino, Jeff's brother-in-law, acknowledged at his deposition that his father-in-law had once pulled a gun on him in his Flea Market office during an "emotional" moment. "I thought it was a joke," said Carlino, who was bought out of Bumb & Associates in 1993 at George Sr.'s direction. Jeff Bumb's memory differs from Carlino's. "He [Carlino] came into my office [after the incident]," Jeff maintains, "highly emotional, highly upset and highly scared." According to Jeff, his father threatened to shoot Carlino in the kneecaps. It wasn't the first time George Sr. had been accused of violence. In 1979, George Bumb Sr. and a business associate named David Middleton were convicted of beating a man who George believed was having an affair with his wife. According to news stories citing the police report, the two men turned the victim over on his stomach, handcuffed his hands behind his back and for 90 minutes beat him about the head, stomach and face using a blackjack, riding crop or electrical wire. Phil Crawford, a former San Jose cop who ran for sheriff in 1982 and is familiar with the case, says that Bumb also allegedly told the victim that if he went near his wife again, Bumb would throw him out of a helicopter. Police initially filed felony charges against Bumb. But Bumb hired criminal attorney Thomas Hastings--now a Superior Court judge--who persuaded the court to reduce the charges to misdemeanors for false imprisonment and possession of a deadly weapon. After Bumb's conviction, San Jose Police Chief Joseph McNamara refused to issue Bumb a concealed-weapon permit. But Bumb went to the county, where permits were handed out by an elected official. Sheriff Bob Winter granted the Flea Market owner a permit to carry a .38-caliber Smith & Wesson. Bumb subsequently donated $11,000 to Winter's campaign. IF JEFF BUMB WAS HAVING a field day revealing long-held family secrets in court, his father, George Bumb Sr., was determined to punish him for it. George Bumb Sr.'s attorneys accused Jeff of improperly diverting more than $400,000 of the family's investment in Cerro Plata, a land-development in Hellyer Canyon, to his alleged mistress, a 5-foot-6-inch, 120-pound hearing-aid saleswoman at the Flea Market named Julie Lykins. Questions about Jeff's use of Cerro Plata-related funds had come up in 1994 during the Bay 101 investigation. State and local investigators then checked into the source of the $62,500 Bumb used as his initial investment in the card club. It turned out that the money was a loan from Environmental Assessment Research, a firm owned by Lykins which had its "office" at a Mail Boxes Etc. location and was drawing payments as a subcontractor on the Cerro Plata project. Deputy Attorney General Paul Bishop, who was then a key figure in determining Bay 101's fate, recalls that Jeff Bumb's failure to properly disclose the source of the $62,500 loan played a role in Bumb's being denied a gaming license in 1994. Within the next four years, the curious financial relationship between Bumb and Lykins in Cerro Plata caught the attention of the IRS. George Bumb Sr.'s lawyers were only too happy to point out in 1998 that Jeff Bumb was "the target of an ongoing federal grand jury investigation." But the feds couldn't prove Jeff Bumb had done anything illegal and they dropped their investigation last year without filing any charges. George Bumb Sr.'s lawyers also never proved that Jeff Bumb had misappropriated funds. On Sept. 30, 1998, a week before the Cerro Plata dispute was scheduled to go to trial, George Bumb Sr. and his estranged son called a cease-fire in their protracted legal feud. The Bumbs agreed on a financial settlement that gave Jeff $1.2 million immediately, $1.5 million in January and $50,000 per month for 62 consecutive months. Sources familiar with the legal struggle say that neither side was especially pleased with the settlement, but everyone wanted to move on. Asked if he was happy with the settlement terms, Jeff Bumb pauses for what seems like an eternity, chewing his gum and gathering his thoughts. Finally, he replies matter-of-factly: "It's settled."

Christopher Gardner

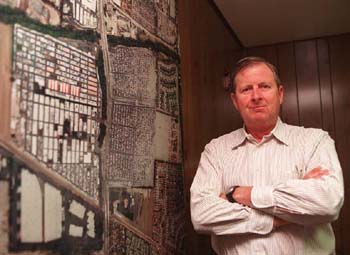

DEALING WITH THE busy Bay 101 is the task of 45-year-old Tim Bumb now, but the second youngest Bumb brother still spends his mornings in his office at the Flea Market, where Brian, the youngest brother, is the manager. The wood-paneled walls are decorated with a family portrait, architectural blueprints and odes to pop culture like a framed collection of 100 Coca-Cola memorial pins, a gift from the soda company. "You see that thing up there?" Tim Bumb asks, motioning his arm to the top shelf of the display rack behind his desk where a snakebite kit rests. The kit is an inside joke between him and his brother George, Bay 101's co-owner. The nasty world of the gambling business, he explains, is "filled with just a lot of bad things ... we figured we would need a snakebite kit along the line." Tim is stockier and more heavyset than his older brother Jeff. But like his brother, he prefers a casual but respectable look: a denim-blue button-down and tan slacks. No tie, of course. During our two-hour interview, he sucks down three cigarettes. Tim Bumb is a man of contradictions. He runs one of the largest card rooms in the state, a house of sin in some churchgoers' eyes, yet he is deeply religious. He describes religion as the most important thing in his life. His religious zeal earned him the nickname in the family of "Tod," a blend of Tim and God. Tim has never sought the spotlight. "I really cherish and prefer my anonymity," he explains. "I don't have any great aspirations of doing something or going somewhere. I like my life the way it is. I love my wife and children." Bay 101, of course, took away a good deal of the anonymity and privacy he so cherishes. Hardly a month seems to go by without Bay 101 or the Bumbs being in the paper, and frequently in a less than flattering light. During the election season last year, sheriff candidate Laurie Smith attacked her opponent Ruben Diaz for taking money from "known gambling interests," i.e. the Bumbs. Diaz later returned the donation, but still lost in a landslide. For all its financial success, Bay 101, he concedes, is a pain in the butt. This year Bay 101, after prevailing in the state Court of Appeals, is allowed to charge progressively higher fees to players at Pai Gow tables. Now Tim and his brothers are readying themselves for life under new San Jose Mayor Ron Gonzales, who, unlike his predecessor, doesn't think card clubs are legitimate businesses. Tim readily concedes Bay 101 is his adopted child. Jeff is the club's real biological father. He and his brothers thought of it as a good investment, like getting in on the ground floor of an IPO. "[Jeff] started this thing; I didn't want this thing," Tim Bumb insists. "I had Premium Pet and I had a toy company running." Tim hasn't spoken to his brother Jeff for more than three years now. But he says he doesn't want to badmouth his big brother, whom he describes as one of the smartest people he has ever known. "I don't even know if I'm that mad at him anymore," he says. And while Jeff finds himself on the outside looking in, Brian Bumb--who, like Jeff, initially didn't reapply when his gaming license application was denied--has become a partner in Bay 101. Brian received a provisional license from the state in 1996. This indicates to Jeff that his brothers Tim and George wrote Brian the letter of recommendation they never would pen for him. "All I wanted was a chance," he says. Brian got his gaming license, Tim Bumb says, without any such letter, and Jeff could, too. "There's not enough money in the world," Tim Bumb says, "to make me cheat somebody, let alone my brother. I still gotta sleep at night." Jeff insists he is not pining away for Bay 101 or what could have been. "It [Bay 101] was mine," he says. "I did it, I'm proud. They did what they did. But it's done." He can drive by the club every day on his way to work and not be consumed by resentment or sadness. He's got his own land-use consulting business now and boasts that he just closed a deal in Long Beach. He still lives within a mile or two of his father and brothers in the Eastside foothills, though their paths rarely cross nowadays. He thinks they purposely avoid him. Asked if he can imagine ever reconciling with his parents and brothers, Jeff Bumb pauses. "I might be open to making up, but I don't know if I would." [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the July 1-7, 1999 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 1999 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.

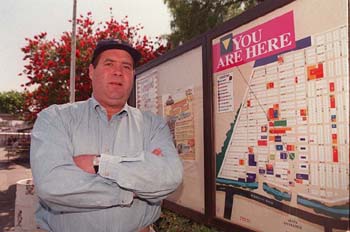

Still Standing: Jeff Bumb, Bay 101's ostracized founder, boasts that despite various local, state and federal investigations over the years he has emerged squeaky clean.

Still Standing: Jeff Bumb, Bay 101's ostracized founder, boasts that despite various local, state and federal investigations over the years he has emerged squeaky clean. Don't Shoot: George Bumb Sr., the publicity-shy patriarch of the Bumb family and creator of the Flea Market, in a rare photo which appeared in California Today magazine in 1980.

Don't Shoot: George Bumb Sr., the publicity-shy patriarch of the Bumb family and creator of the Flea Market, in a rare photo which appeared in California Today magazine in 1980.  God and Man: Tim Bumb, co-owner of Bay 101, says religion is the most important thing in his life. Family members sometimes refer to him as "Tod," a blend of Tim and God.

God and Man: Tim Bumb, co-owner of Bay 101, says religion is the most important thing in his life. Family members sometimes refer to him as "Tod," a blend of Tim and God.