![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

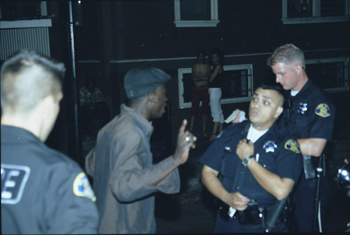

Photograph by James M. Mohs SJPD Blue: With last call at 1:30am, and music shutting off in the nightclubs 15 minutes later, the police strategy is to evacuate downtown of its nightclubbers and bar patrons, which number anywhere from 3,000 to 10,000 on any given Thursday, Friday or Saturday night. Do You Know the Way Out of San Jose? Closing time in downtown San Jose's nightclub district has been likened to martial law, and club owners say the tactics are driving good customers right out of town By Najeeb Hasan SO MUCH for the moon. It's a few minutes before the second Saturday of June, and the yellow moon is just about full. Its presence, though, seems of little consequence in San Jose's downtown, where people are mesmerized by thumping beats and $6 drinks. At least for now, their gazes, both literally and symbolically, seem to be directed not up above but, impatiently, toward the bouncers handling the line snaking around the corner of the Cabana Nightclub on South First Street. Sergio Carabarin, a sergeant in the San Jose Police Department, knows the scene well. Clean-shaven, with laugh wrinkles clustered around the corners his eyes, the easygoing Carabarin, married and a 20-year veteran of the force, sees himself as part of the scene. Indeed, without his SJPD windbreaker, Carabarin, wearing jeans and a green fleece pullover, would more than likely melt into the city's nightscape--a patron too old, perhaps, for the Cabana but well-suited for the Improv or Eulipia. From Wednesday nights to Saturday nights, Carabarin patrols as a ranking officer in the city's downtown entertain-ment district. San Jose's police department, unlike those of most cities in the country, sets aside and trains a group of police officers strictly for the purpose of managing the security needs of downtown's night life. The strategy, one that any resident familiar with downtown cannot but help noticing, has been both criticized--mostly for its emphasis on police visibility and its closing-time procedures--and praised--for its apparent clockwork efficiency. The affable Carabarin is, perhaps, the perfect officer for the Police Department to have straddled between the two extremes; at times, he appears more diplomat than cop. Equally conversant in trading jibes with burly bouncers and pleasantries with high-strung nightclub owners, Carabarin is adept in performing exactly what critics of the entertainment district's policing strategy maintain the strategy doesn't allow for: community policing, a sort of Cheers-style policing where everybody knows the police officer's name. The infuriating catch for the club owners is, of course, that Carabarin is one of the few officers on the beat who do any sort of community policing; most others, owners contend, remain virtual strangers to the community because they stay sequestered in their squad cars. Also, some owners say, officers sometimes treat patrons rudely and generally create a hostile atmosphere in the downtown that San Jose has spent millions to make a friendly and inviting place. And while nightclub owners publicly suggest and privately grouse that the department's strategy drives customers away from downtown and to places like Campbell, Los Gatos and Santana Row, they concede that Carabarin, while defending the Police Department, projects an empathetic presence. He takes their criticisms with a smile, rebuts them with the Police Department's perspective and allows room for potential changes--that is, changes of city rules and regulations, not of the department's policies. Undoubtedly, the most glaring example of when the Police Department's downtown strategy conflicts with the interests of nightclub operators is San Jose's now-infamous closing-time procedure. It's a method dependent on the blunt visibility of police officers and police cars that critics describe as more similar to a military exercise than to community policing, and it's a procedure that's just about unique to San Jose. For Carabarin, however, closing time is when he could prove why San Jose is--as city politicians and the department's top brass like to remind anyone who will listen--the safest big city in America. In the early morning, at 10 minutes after 1am, Carabarin gathers together his officers at the parking lot of the post office on the corner of St. John and Market streets. On a typical Friday or Saturday night, there could be as many as 35 to 45 officers and their squad cars present waiting to receive their assignments. Thirty to 35 of these officers are coming off swing shifts that ended at 1am and are working overtime; the remaining seven are part of Carabarin's nightly cruise-management team that bikes and drives around downtown handling cruisers on Santa Clara Street and writing tickets for infractions as jaywalking, public drunkenness, public urination or littering. With last call at 1:30am and music shutting off in the nightclubs 15 minutes later, the strategy is to evacuate downtown of its visiting population (on a good night between 7,000 and 10,000 people; on a bad night, between 3,000 and 5,000) by 2:15am. Streets are closed off, and traffic is diverted straight to the freeways; nightclub closings are staggered by five to 10 minutes to keep the crowd flowing. Bouncers are trained by the police to herd the exiting patrons off the streets and toward their cars (at the Cabana, bouncers use whistles to keep the herd moving); bright lights are shined on the dawdlers and any potential troublemakers; and parking lots and other trouble spots are monitored after the nightclubs are emptied. All this in a light-speed-like 20 minutes. Carabarin usually stations himself in the SoFA district during closing time. At the intersection of South First and San Salvador streets, where a major club--Zoë, Agenda, Cabana and Spy--sits on each corner, the pavement slopes upward to give the police officers a higher vantage point. First Street, San Salvador Street, Second Street and Third Street are all closed off in such a way as to divert all traffic south on Second Street. Four squad cars are lined up on the north end of the block, seven or eight on the south end--all the police cars are purposely parked in the field of vision of the exiting patrons; in fact, if the nightclubbers loiter too much, the officers simply train their bright headlights on the customers (on this night, the headlights were already on when Carabarin got there, prompting him to instruct that they be turned off unless things got troublesome). The police officers are congregated in the intersection watching the night life evaporate. "Look at them," Carabarin points out. "They're not moving. If you let them, they'll take over the whole street and make it into a street festival. If we didn't block off everything, people would be all over the street, walking through red lights with cars coming the other way." But what would happen, one has to wonder, as Fil Maresca, the chair of the South of First Action Committee (SoFAC) does, if all the patrons weren't dumped into the street during the same half-hour time period? What if the clubs were allowed to remain open for music and dancing, with alcohol sales stopped and staggered closing times, as they are in other major cities? What if after-hours options included restaurants that were open, spreading out patrons who might want a late-night snack or a cup of coffee? (Indeed, both the Police Department and nightclub owners hope that the recent approval of a location for a Flames diner downtown by the Redevelopment Agency may help fill this gap.) What if the troublesome parking lots were developed into after-hours coffee shops and eateries, and patrons were forced to park and walk in all directions to get their cars, or to take public transit, as they are in other cities? It's a lot of what ifs, but not too many for a city that has spent more than a billion dollars in redevelopment funds aiming to make itself into, in the words of Mayor Ron Gonzales, "a world-class city." The lack of city leaders' attention to these questions has affected the spending choices of another group of potential club-goers, out for a good time on this same moonlit night. In a car less than a mile outside the city center, a group of college and grad students celebrating one of their friends' acceptance to Brown University's grad school has decided, unanimously, to avoid downtown San Jose altogether. They drive a giant circle from Willow Glen, along Highway 87 to Japantown. "When you're young and you're out and you see all these cops around, there's an immediate antagonistic tension. You're checking yourself even if you 're not doing something wrong, to make sure you're not doing something that might be minutely wrong. It's not a very hospitable environment. You just don't want to hassle it," says one student named Kate.

Night Beats: An unidentified woman knocked briefly unconscious after an altercation on South First Street lends credence to the notion that downtown's nightclub district warrants stepped-up police presence. No arrests were made. Intimidation Factory The stories and anecdotes about how policing has choked the ambience of downtown night life are endless. Mark Johns, a local house DJ who used to spin at Waves and now Zoë, remembers the night of San Jose's Da Bomb concert at the San Jose Arena this year. One of his performers, a DJ traveling from San Francisco, was caught in the crossfire of the Police Department's containment strategy and was unable to make it to Waves on schedule. "They closed off the [streets]," Johns remembers. "The DJ was supposed to play at midnight and didn't get there until 12:45. He finally had to show the police his vinyl to get through. They just want to be a big Los Gatos or a big Willow Glen. They just want people to get out. Welcome to San Jose; get out." One bar owner remembers with frustration the police's unfamiliarity with his clientele. A patron had come to his bar for his birthday. At the end of the night, he wobbled outside and headed to his downtown home, on the same street as the bar. Because he was inebriated, he fumbled with his keys and had some trouble opening the door to his apartment building. "The cops pulled up and arrested him," says the owner incredulously. "They charged him with drunk and disorderly. What's the point? He's not out there selling drugs; he weighs about 90 pounds. How hard would it have been for the cop to take his key, open the door for him and let him inside?" Then, there's the story of a customer, who against his better judgment, went to go use the ATM too close to closing time. "Next thing you know, the guy's on the ground with two cops on him," a bar owner says. "The police are cracking down on harmless yuppies. Is it the cops' fault? Well, the cops are under direct orders to clear downtown. It's the idiots that made this decision that says downtown has to be cleared by 2am. Find me another city in the country besides Mayberry who does that." It's these kinds of little stories--and it seems every bartender downtown has a similar tale--that build up and worry merchants whose incomes depend on happy, unmolested customers. While the Police Department emphasizes that preventing crimes from occurring is better for public security than arresting people after crimes occur, the merchants counter that crime prevention doesn't have to mean intimidating their paying customers. Already, merchants believe, much of the most valuable demographic (older people with disposable incomes) would rather spend their money at places like Santana Row, where the police presence is less visible. Soon after the Police Department initiated its current strategy for policing downtown in 1997, the San Jose Downtown Association formed a committee for the entertainment zone; because, at first, night-time establishments were required to foot the bill for the extra police (the city now picks up the tab, which is about $691,000 per fiscal year, though the budget will soon be slashed by 30 percent), the committee was made up mostly of the businesses that had to pay up. Understandably, one of the primary concerns of the merchants was that they had to pay money to the city for security in their district. In 1997, for example, 17 establishments were scheduled to compensate the city $693,288.96 annually--Studio 47 and Club Vertigo each had annual bills that exceeded $80,000; San Jose Live! was billed more than $150,000; the Agenda and the Cactus Club both around $25,000 (in 1998, though, after much wrangling by the merchants, the scheduled fees were considerably reduced by the city). However, even in those early years, price was not the only concern. Operators realized very quickly that (1) the Police Department's new plan wasn't anything close to community policing; and (2) they were far more satisfied with the old way of doing things; before 1996, they still had to pay for security, but the police officers hired worked for them, not the department, allowing them to get to know their clientele. "My feeling is that ... [the new plan] is not currently nor will ever be as effective as the method it replaced," wrote Michael Trippett, of the Cactus Club, in 1997. Trippett's letter, addressed to Scott Knies, the Downtown Association's director, was one of a batch of letters from concerned businesses that were forwarded to then-Mayor Susan Hammer and members of the San Jose City Council. He continued: "Under the new plan, police officers float throughout the area. There are less officers than before. They do not provide the visual deterrent that having officers at the front door used to have." In another letter, also forwarded to Hammer and the council, Club Miami's Elizabeth Flores wrote: "I've noticed officers making unnecessary approaches to patrons using intimidations. For example, three weekends ago, my fiance, Edward, and I were standing at the top of Club Miami's staircase communicating to our manager ... and next to us were two of the EZ [Entertainment Zone] officers who noticed us. As my fiance made his way downstairs to Emma's food express, the officers followed him, grabbed and pulled Edward by the arm and took him outside and interrogated him, indicating that they suspected he was carrying a gun. This situation was uncalled for. Thank God!! this incident did not occur with anyone of our patrons. They would ... [have] been humiliated like Edward was and probably would have not returned back to the so-called entertainment zone." And finally, in yet another example, Michael Gurnett of Hamburger Mary's Restaurant & Nightclub also wrote to the Downtown Association voicing early concerns in late 1997: "I can speak only from my experience, specifically since May, 1997, in regards to the new Police program for nightclubs. As a result my business was greatly affected. My sales are off $136,907.34 since May in '97. ... My customers had a huge reaction to how they perceived that they were treated by the San Jose Police."

Coppin' Attitude: In addition to evacuating the nightclubs, downtown policing also includes a 'cruise-management' team that pulls over suspected cruisers and writes tickets for 'quality of life' violations like jaywalking, littering or public drunkenness. Law and Ornery The death of 21-year-old Jason Scott Cooper in a 1996 brawl at the (since closed down) Oasis perhaps helped most to lay the foundations of a new policing plan for San Jose's entertainment district (Metro, "Worst Case Scenario," May 2, 1996). Before 1997, nightclubs had the responsibility to hire their own security, which was usually made up of off-duty police officers trying to earn some extra cash. The Police Department had a policy of allowing off-duty officers to work privately but still wear their SJPD uniforms; the uniform's deterrent effect was one of the main reasons nightclub owners hired off-duty officers as opposed to private security. The Oasis brawl, however, highlighted the inherent conflict of interest in allowing an officer to outwardly represent the city and the city's legal codes but actually work for a nightclub and under a nightclub's own rules. "This [concept] was a black spot on the Police Department's clean record," says police auditor Teresa Guerrero-Daley. "It could have been an Achilles heel on an otherwise very respectable, very progressive Police Department." Cooper's death, during the waning hours of one of the club's regular Thursday-night hip-hop events, was covered by the city's local media, including San Jose State University's Spartan Daily. It was the Spartan Daily's article, which quoted a witness criticizing the inaction and alleged misconduct of off-duty San Jose Police Department officers moonlighting at the Oasis during the night of Cooper's murder (not only were the moonlighting officers ineffective, but some also disappeared when the on-duty police showed up), that (along with other reports that police officers weren't always paying taxes on their off-duty earnings) convinced the department to devise a new policing plan, says Joe Brockman, then a captain in the department, now an investigator in the district attorney's office. "I was reading the articles in the paper," Brockman says, "and the Central Division [downtown] was my division. I went to my boss, and I said I have an idea to deal with the pressure we're getting and to deal with the nightclubs. ... [One of the problems was] when clubs closed at night, patrons lingered, fights broke out in the parking lots and we had to pull units from Willow Glen and the rest of downtown, stripping other units. So I proposed to him that we create and use a force for those establishments, and we would run it as an on-duty assignment." After his proposal, Brockman's idea took a life of its own. "It was timely," he says. "Everybody was reading those same articles." And so, the transformation in policy--spurred along by Brockman's reaction to media reports and numerous other complaints Guerrero-Daley had been receiving about the conflicts of interest of moonlighting officers (Metro, "Security Matters," May 2, 1996)--took place. Cops could no longer work privately at nightclubs and under the management of club owners. Instead, the plan that Brockman created required that both the city and merchants chip in to fund a special overtime unit to police the entertainment district. "If you talk to some club owners, they wanted officers standing next to their doors," Brockman says. "You can't have stations outside the club; you have to manage the entire area. For example, if you talk to hotel owners [downtown], they were delighted that we now patrolled the whole area. From my perspective, I was better policing the entire area. I wasn't stripping other divisions or neighborhoods, and I was policing not just nightclubs but also the adjacent areas."

Standing for Safety: Police agree that positive interaction with the public is key to community policing, which can't be achieved if they stay in their patrol cars. The Thick Blue Line The reason why San Jose (and virtually no other city in the United States) requires a policing strategy so heavily dependent on blunt visibility and rapid execution is, according to Chief William Lansdowne, that the cluster of nightclubs in the city's downtown is denser than in any other entertainment district. In other cities, Lansdowne argues, there are more-diverse mixes of nighttime options, whereas in San Jose, nightclubs that cater to a younger, brasher crowd are the predominant option. "I think it's more about the venues downtown," he says. "I don't think there is another city you will find that has such a high concentration of liquor establishments. It's not about dinner clubs, soft music, jazz. It's not for laid-back older people. They're gone by 11 o'clock. It's about nightclubs and the dating game." And as for his critic's suggestions that the department handles closing time like a SWAT exercise? "It's not even close to a SWAT team," Lansdowne responds. "They try to be as low-key as possible. I'm not sure what [the nightclub owners] see; when I'm down there, the people are glad to see the police. [Our strategy] has been developing for 20 years. There used to be bumper-to-bumper cruising, stabbings and shootings. The highest number of violent incidents in the city occur in the downtown area after 11 o'clock on any given night. There's fewer problems with a strong presence. So when we police, we have to police for the worst conditions, not for the best. There are specific nights when it's slow, but reality can change very quickly." While Lansdowne hints that if he had the personnel and the money, he might experiment with an after-hours policy, he remains skeptical that leaving nightclubs open longer would solve any problems. The after-hours policy, a concept endorsed by the Downtown Association that has been circulating among club owners and their advocates for some time now, is one of the key concessions that bar and nightclub owners want the city to make. The logic goes that if nightclubs are permitted to remain open (serving coffee, soft drinks and snacks) one or two hours after the flow of alcohol has been shut off, then the patrons would naturally trickle out on their own accord instead of being prodded along by the police en masse. The police contend that such a policy would only force them to work longer hours because they would still have to monitor the parking lots after the patrons leave at later times. And according to Lansdowne, patrolling an after-hours downtown would cost the Police Department an additional 24 officers, which, at $100,000 per officer, comes out to $2.4 million. Besides, he counters, cutting the alcohol but leaving the music on in nightclubs has very little effect on party-goers. "It's a myth about what the bar owners are telling us--coffee doesn't do it," he says. "You need open air, bright lights; if you're still in a bar, then it's just a continuation of the dating game." To Lansdowne, San Francisco is an example of what San Jose shouldn't be, not what it should be. "San Francisco is a good answer [to the after-hours policy]," he says. "We have a very aggressive policy in dealing with crime and drugs. You can go to some other cities, and [for example] you can see their prostitutes. You can't find that in the city of San Jose. This after-hours thing will turn into a rave mentality, and it would be a difficult problem if we had it in San Jose because everybody in the South Bay would be coming here." Lansdowne does, however, seem more receptive to the concept of more officers without police cars and says he'd like to increase foot and bike patrols and perhaps even portray a softer image, without squad cars, during closing time. "We are experimenting with that," he says. "But cars have some advantages that bikes don't. They give officers a ready source to confine people; they give them mobility and speed while policing." Club owners would love to see a softer image. "If cops are walking through downtown, they would fit into the community," says one. "A cop driving by in a squad car doesn't do anything. They're in their air-conditioned squad car; they're not going to get out. A lot of them are just hanging out to check out the girls. That's what we don't need. We need these guys out talking to people. We need neighborhood cops." Meanwhile, Lansdowne has no worries that his department's strategy adversely affects the interests of businesses downtown--if anything, dwindling business, both he and his assistant chief, Thomas Wheatley, assert, has more do with the recession than with the police. "I know it's always busy downtown," says Lansdowne, who also says he does go, from time to time, to observe the policing in the entertainment district. "From the looks of some of the crowds, they [the club owners] are probably making a lot of money."

Weapons of Math Destruction: San Jose Police Chief William Lansdowne says patrolling an 'after hours' downtown such as the one promoted by downtown merchants would require 24 additional officers, costing the city $2.4 million. Suburban Cowboys It's still early Saturday morning, and the Police Department's Carabarin is strolling south along First Street. He ducks his head into Cafe Matisse and picks up copies of the week's free newspapers. These, he says, are his intelligence. He goes through them each week to keep abreast about shows coming downtown and to learn about what kind of crowds they bring along with them. Carabarin takes policing his district seriously. He's a realist who understands that, given that his overriding duty is to keep the flow of exiting club-goers as smooth as possible, he doesn't have the manpower to make arrests for every violation that occurs. Earlier in the night, he pulled over two women who threw an empty beer bottle from the window of their car. There were two clear violations: littering and, more importantly, drinking while driving. Instead of running their licenses, he gave them a dose of old-school justice, instructing them to drive around the block and pick the bottle up. But still, Carabarin smirks when asked about cities like San Francisco, where policing policies are even more lenient in the entertainment districts. For Carabarin, comparisons of San Jose to other cities, such as San Francisco, are based on fallacies; he thinks San Jose's policy works just fine for San Jose. "People have said, 'You intimidate patrons; you intimidate customers,'" he says. "But the customers act like we aren't even there. They walk right around us when we close. We have become part of the entertainment-zone scenery. Sometimes people do ask us, 'What's going on? Why are there so many cops?' We say, 'Nothing.' We have become very adjusted to downtown. It has to do with people's perspective of the police. Every once in a while, people will have the attitude that we are not part of the community but apart from it. But they don't need to fear us. We're here to ensure that if people want to have a good time, they can." But questions regarding alternative policing strategies still persist. This time, it's Jacek Rosicki, owner of both the Agenda and Zoë in the SoFA district, who runs into Carabarin as he's exiting Matisse and walking south toward Agenda. Rosicki, seeing his chance, immediately pounces on Carabarin. And this time, among other initiatives (including the idea of allowing under-21 crowds into downtown clubs for certain events), Rosicki is pushing experimenting with the after-hours policy. Rosicki, using the example of the 11th Street Corridor in San Francisco where, as in SoFA, there is also a dense cluster of nightclubs, insists to Carabarin that such a policy would be much more customer-friendly than the current mass-exodus procedure. "There's lots of cops on First Street," Rosicki says to Carabarin. "The problem wouldn't exist if we had extended hours like they do in San Francisco." "The only problem is that everybody knows that the problems don't happen here, but out there," Carabarin responds as he points to the lots. "If we extend the hours, I guarantee that when the alcohol stops, I lose half my crowd on its own," retorts Rosicki. "We do that anyway. We stagger the closing," Carabarin fires back. Carabarin, however, has backup for his point, which mirrors conventional law enforcement wisdom much more closely than Rosicki's. "So the club owners are complaining that people are leaving when they see police cars and want to wait until 3 or 4 o'clock [so people could trickle out]?" asks Steve Tacchini, a captain in the San Francisco Police Department North Beach district, which includes many of the city's nightclubs. "It doesn't work that way. You keep them open until 3, they leave at 3. You keep them open until 4, they leave at 4. The club owners don't have a valid argument. Whenever alcohol has been involved, there's going to be problems." "San Francisco is San Francisco; San Jose is San Jose," Carabarin says later. "San Francisco has a lot more stuff. Have you ever gone to San Francisco and not found a restaurant that's open 24 hours, and you can eat anything you want? They're truly a 24-hour city. We're a different type of city. Everybody has different opinions of what kind of city we are, but we're not San Francisco. I took my son once to the city [San Francisco] and saw people smoking pot, drinking, urinating all on the street. I was looking at these violations and said, 'My God, if we had these violations in San Jose, we'd be all over it.' San Francisco is smaller, and it needs 2,100 officers; San Jose is bigger, and it needs a thousand less officers. People are always like, 'Why can't we bring in Los Gatos people? Why can't we bring in Palo Alto people?' Because we're not Los Gatos or Palo Alto. We're San Jose. When people accept who they are, then we'll grow into something. We don't cater to our identity; we want other identities." Meanwhile, back in San Jose's downtown, bar and club owners, while hastening to say that their relationship with the police has improved over the years, are still not convinced the current strategy should be the final one. "Here's my take on it," says one owner. "Downtown San Jose has a huge amount of potential--the landscape, the rental units, the retail is not there yet--but the potential building blocks are there to be the capital of Silicon Valley. The problem is that the city is not planning for this. You have two types of people who come downtown: those who come and spend money to support businesses downtown and, on the other side of the coin, groups of people who come without a penny, who come to cause trouble. But its almost as if the police don't want to settle this problem; [their strategy] has a reverse effect. The troublemakers love confrontation, while guys like you and me who want to come here and have a cocktail with their girlfriend won't do it because of the police. Nobody believes it's not a good idea to have more police around. It just doesn't have to look like there's a terrorist attack."

Hot Spots Policing of entertainment districts commands new attention nationwide By Najeeb Hasan WITH THE BOMBING of a nightclub in Indonesia and public safety disasters at nightclubs in Rhode Island (after a pyrotechnic display gone awry) and in Chicago, the concept of ensuring the safety of the public in entertainment districts has become a hot topic within urban police departments. Different cities have been experimenting with different methods; some incorporate the club owners into the process while others depend mostly on city services. *In Minneapolis, Minn., home to the largest collection of nightclubs between Chicago and Seattle, an entertainment task force--a group of club owners, police officers and fire inspectors--meets at least once a month. The task force was set up after club-related riots in 1998. The result? The number of clubs has increased while crime has decreased. The relationship between the club owners and the city employees was testy at first, until club owners realized that their input was being taken seriously. According to the Christian Science Monitor, since 1998, 911 calls related to certain clubs have decreased considerably, club and bar capacity has increased from 17,000 to 22,000, and thefts have decreased from 350 to 250 per year. *In Austin, Texas, the issue is still debatable. Sixth Street boasts more than 30 bars in a span of seven blocks--with at least a dozen more on neighboring streets. Bars allow only patrons older than 21, but underage people still walk freely about the area. Officers line the street corners--not in squad cars but on foot, on horse or on bike. An average Thursday, Friday or Saturday night sees about 28 officers, four mounted patrol units and an undercover street-response unit. *In New York City, 24.3 million patrons visit nightclubs annually, contributing more than about $2.9 billion to the city's economy. According to Gotham Magazine, the number exceeds the number of people going to Broadway shows, sports events, the Empire State Building and the Metropolitan Museum of Art combined. More than a third of club-goers are from outside New York City, and 89 percent say the night life was their main reason for visiting the city. However, as in San Jose, a tension between club operators and police exists. Clubs are routinely closed down; a request by club owners to be permitted to hire off-duty cops was recently rebuffed; and a club owner complains that the industry is "singled out for a standard that no one can live up to."

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com. [ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

|

From the July 3-9, 2003 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.