![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Head Trip

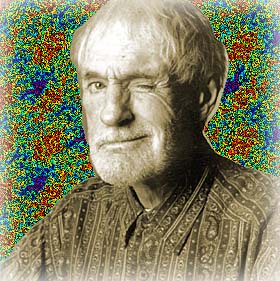

Jay Blakesberg Cosmic Jester: Timothy Leary taught a generation how to turn on. New media blitz canonizes Summer of Love LSD guru Timothy Leary By Greg Cahill HE TUNED IN, turned on and dropped dead. Now, one year after his death at the age of 76 from prostate cancer, '60s counterculture icon Timothy Leary is back. True to form, the return of Leary--part intellectual, part snake-oil salesman--is bolstered by a media blitz befitting the swirl of shameless self-promotion that shadowed the late LSD guru during his lifetime. And it's all neatly timed to coincide with the 30th anniversary of the Summer of Love that Leary helped cultivate into a drug-sated, Utopian, flower-power happening. The Harvard professor-turned-drug-flack--whom Richard Nixon once called the "most dangerous man in America"--is the posthumous author of the newly released book Design for Dying (Harper Edge, $24), co-written with cyber freak and Mondo 2000 creator R.U. Sirius; the subject of Timothy Leary's Dead, Paul Davids' new film documentary; and the focus of Beyond Life With Timothy Leary (Mercury/Mouth Almighty), a CD compilation that features excerpts from Leary's lectures interspersed with offerings by poet Allen Ginsberg, industrial rocker Al Jourgensen of Ministry, and the Moody Blues, reprising their hit song "Legend of a Mind." Adding to the buzz factor, Michael Horowitz of Petaluma--father of actress Winona Ryder, who delivered the eulogy at Leary's memorial service--served as a consultant on the film and book projects. The hype surrounding these releases is geared to elevate Leary to new heights--even for someone who experimented liberally with LSD, psilocybin and other powerful psychoactive chemicals. For instance, the press release distributed by Mercury Records draws a comparison between Leary and Socrates, the Greek philosopher put to death for the crime of impiety. The book--a patchwork of cyberspeak, ancient rituals and acid-drenched schematics about consciousness--declares that Leary may achieve the immortality of the pharaohs. And the documentary, which Spin magazine described as a cross between a hippy elegy and a boomer snuff film, often dissolves into little more than a loony Leary lovefest. Taken as a whole, however, the three works capture the quirky essence of one of the most controversial figures of the century--a former West Point cadet-cum-Peter Pan suffering from terminal adolescence and seeking to lead an entire generation of Americans to Never Never Land. The projects also reveal sharp contradictions: the cosmic clown who yearned for recognition as a serious psychic explorer; the aspiring mystic who lacked spiritual discipline and believed to the end that the brain--and not the soul--is the repository of consciousness; the ardent anarchist who craved the special status of celebrity. And like the strange life that Leary led, his afterlife also harbors a mondo-bizarro quality: Davids' film documentary closes with graphic (albeit fake) scenes of cryonic specialists surgically removing Leary's head, which they then place in an ice-filled picnic cooler before deep freezing it in the hope that science might find a way to revive it. The ultimate head trip.

Take a virtual tour of Leary's home. Massive metalist of Leary links. Part of the Hyperreal Drug Archive with more Leary links. Information about the CD.

IF EVER there was a suitable subject for an Oliver Stone film, it is Timothy Leary. Raised in an Irish Catholic neighborhood in Springfield, Mass., he was the son of an abusive, alcoholic dentist who abandoned his family when Leary was 13. Still, Leary quickly moved onto the fast track of the establishment against which he later rebelled. As a West Point cadet, Leary was shunned after being caught drinking with upperclassmen. He later attended the University of Alabama, where he studied psychology and got expelled for sleeping in the girls' dorm. He joined the army, training as a clinical psychologist. He married and enrolled at UC-Berkeley, where he helped to conduct landmark research that showed that one-third of patients receiving traditional psychotherapy actually got worse, one-third stayed the same and only one-third improved. On his 35th birthday, Leary's wife, Marianne, committed suicide. Depressed, Leary quit his post at the university and traveled to Mexico, where he ate magic mushrooms. A colleague argued that the transformative quality of the drug might be the link to the psychological metamorphosis they had been looking for to break the barrier between patient and psychotherapist. Leary was unconvinced. He took a post at Harvard University, returning to Mexico and again sampling psilocybin. This time it changed his life. "I gave way to delight, as mystics have for centuries," he recalled, "when they peeked through the curtains and discovered that this world--so manifestly real--was actually a tiny stage set constructed by the mind." He played that stage well.

Yoga Bears It: Leary in full trance mode from his '60s heyday. After turning on such notable intelligentsia as author William Burroughs, Beat writer Jack Kerouac and jazzman Thelonious Monk, Leary began a close association with fellow Harvard professor Richard Alpert (a.k.a. Ram Dass). When Michael Hollingshead, a British philosophy student, turned Leary on to LSD in 1961, Leary hailed the event as "the most shattering experience of my life." Two years later, Leary and Alpert were fired from Harvard for their experimentation with LSD. The pair took their show on the road, settling into a lavish upstate New York estate and eventually getting busted by lawman G. Gordon Liddy (who later gained notoriety for masterminding the bungled Watergate break-in--and who eventually ended up on the lecture circuit "debating" Leary). On the advice of media critic Marshall McLuhan, Leary launched a savvy campaign to spread the LSD gospel by stressing its reputedly positive effect on creativity. He recorded albums with Jimi Hendrix, sang "Give Peace a Chance" with John Lennon and Yoko Ono and ran unsuccessfully for governor of California. He got busted for hash and acid in California--a setup, he claimed--and was sentenced to 10 years in state prison. In a daring midnight escape, he shimmied a cable to freedom and fled to Algiers, where he lived with exiled Black Panther leaders. He traveled to Switzerland to meet chemist Albert Hoffman, the inventor of LSD. After completing his sentence in 1976, Leary moved to L.A., socializing in Hollywood circles and starting a new career as a cyberpunk. In 1978, author W.H. Bowart claimed that Leary had worked for the CIA and became a government snitch in a number of drug cases. Leary publicly denied the allegations, but Bowart on his own Web site insists that Leary later admitted his CIA connections. Leary wrote several books he said were transmitted from beings in outer space. Last year, his own cremated remains--sans head, of course--were carried into orbit aboard the space shuttle. IN THE WAKE of his death, Leary is still dogged by the oft-held view--expressed in Timothy's Leary's Dead by an LAPD officer, and reiterated even in progressive circles today--that his focus on LSD helped bring about the moral decay of society. Yet his life's work, to some extent, helped foster the personal growth movement and opened people's minds to environmentalism, women's rights and various liberation movements. Meanwhile--thanks to the Internet--Leary's aggressive stance as a wily pitch man for hallucinatory drugs remains intact, a position that seems oddly outdated. "Neuro-transmitter chemicals are information codes [that] allow us to activate and boot up circuits in our brains. Young adults should be taught how to use info-chemicals in order to navigate their brains," he proclaimed on his official Web site, an unapologetic advertisement for illicit drug use. "It is the duty of every free person, it is the patriotic responsibility of every American, to oppose the attempts by politicians, police, and medical authorities to control who and what adults put in their bodies." Leary lived up to those ideals to the bitter end. A few years ago, while LSD enjoyed a comeback with America's youth, Houston police busted the then-aging acid guru, not for powerful mind-altering hallucinogens but for smoking a cigarette at the municipal airport in protest of no-smoking laws.

Timothy Leary's Dead (Unrated: 80 min.), a documentary by Paul Davids. [ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.