![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Movies Index | Show Times | San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

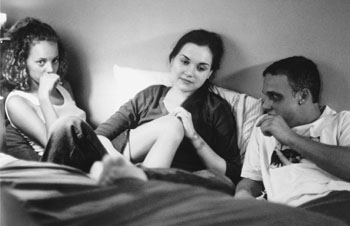

Wake-Up Callers: Larry Clark's affectless teens (Bijou Phillips, Rachel Miner and Brad Renfro) run amok in 'Bully.'

Kids Today

Larry Clark's avant-garde sheen can't hide the exploitative heart of 'Bully'

By Richard von Busack

IF LARRY CLARK had only been a little faster, he might have gotten away with it. His new film, Bully, repeats the bid for art-house fame his 1995 film Kids achieved. Bully is based on the true-life murder, in 1993, of Bobby Kent, which occurred in the suburbs of Ft. Lauderdale, Fla., a crime novelized in the book of the same title by Jim Schutze, the Dallas bureau chief of the Houston Chronicle.

No one would call the Kent case a thrill killing, because the participants (seven of whom were eventually imprisoned for the crime) didn't derive much pleasure from it. The victim was a would-be thug weight lifter, a user of steroids and a fancier of that loathsome bully-boy urban music that sounds like pit bulls singing in chorus.

Kent nurtured both an obsessive fascination with gay porn and an obsessive loathing of homosexuals. He was also supposedly a sadist in bed--one of his killers accused him of raping her. The ring leader of the killing, Marty Puccio, claimed that Kent had been tormenting him since he was a child, though other observers noted that the two were so close many thought they were lovers.

Naturally, since the murder of this young man occurred in a better-than-average suburb, pundits were quick to make the three-way connection between wide-open streets, affluence and moral decay. Schutze did nothing to counteract that impression. He used the alligators on the edge of the Broward County real estate developments as symbolic fauna, just as Joan Didion uses coyotes when she's writing about blanked-out Southern Californians.

Reading about these strip-mall patrons and Geto Boys listeners, The New York Times Book Review spouted as reliably as Old Faithful, calling Schutze's book "an indictment of suburban values, and of an aimless, violent middle-class youth culture that is depraved because it is morally--not economically--deprived." No museums down there--not that Larry Clark's art (portraits of naked Oklahoma junkies) would enlighten the Florida brats much.

When The New York Times called director Clark's previous movie Kids "A wake-up call to the world," it was congratulating Clark's bravery for exposing the too-much-sex-too-soon crowd in Manhattan. According to Bully, the suburbs are just as perilous. We're in the same position as the child who wouldn't take a bath after seeing Diabolique and is now terrified to take a shower because of Psycho.

WHERE, IF ANYWHERE, are the blank-eyed teenagers not running amok? Malaysia? (As critic Jonathan Rosenbaum joked about The New York Times' last worldwide-wake-up call, Malaysian rice farmers really do need to know about the problems of privileged Manhattan skateboard kids.)

On the whole, scriptwriters David McKenna and Roger Pulis followed Schutze's prose line by line and incident by incident. The writers even included the moment when Lisa's mother complains that back in the Bronx, people looked after each other. The Bronx!--not like these suburbs where families live apart. (The book makes the prejudice clearer--in the Bronx, Mrs. Connelly says, "Everyone knew their place." That Archie Bunkerism is purged to reflect Clark's New York partisanship.)

Schutze didn't have a single attractive character in the book, so the makers of Bully changed two of the principals into tender lovers. Clearly, Clark taps into the same ethereal qualities Terrence Malick used in Badlands. To give us someone to hope for, Clark makes the instigators of the killing a pair of beleaguered young lovers.

Lisa Connelly, a pudge in real life, is played by the seal-svelte Rachel Miner as a dreamy girl who hopes to have Marty's child (though the real Lisa panhandled to get money for the abortion). Marty is her sensitive lover, played by Brad Renfro in the best sweat-glazed, aching post-James Dean style, though according to Schutze Marty sometimes slugged Lisa and called her a fat bitch.

The victim, Bobby, is white, though in real life he was of Iranian parentage (their name was Khyam before they changed it to Kent). Bobby and Marty's re-creation of hurling footballs at the heads of retarded kids has also been left out. Bobby, the murder victim to be, is played by Nick Stahl, less a bruiser than a twerp. He's expressionistically mad, like the silent movie actor Conrad Veidt, whom he resembles.

Stahl gets to act big, but he's not big. In one typical scene, Stahl lets the mirror have it with a mouthful of spit. Mistreating a mirror is the hallmark of the overcompensating actor. Stahl doesn't have a short desperado's power, and thus you can't see what it is that keeps the larger boy in check.

These kinds of elisions and tidying up were also a part of The River's Edge, a movie bound to be cited by partisans of Bully. Yet Tim Hunter's 1986 movie wasn't "a wake-up call to the world"; nothing was that certain, and it had chill and mist in the air.

There was something in Hunter's film of the mood caught in the old ballads, where the dead girls lay by the banks of the river, murdered by their lovers. Clark evinces more interest in modern sensation, and the problem is that he doesn't go far enough or fast enough.

THE FILM starts out with two girls at the mall: Lisa and her promiscuous pal Ali (Bijou Phillips), who wears the smallest tank top in the history of the movies, go out for a sandwich. They pick up Marty and Bobby at the sandwich shop where they work; they park, and Ali presents her barely covered crotch and ass to the camera as she buries her head in Bobby's lap.

Meanwhile, Lisa and Marty go to town in the back seat; it's effortless coupling, a teenage dream of the way things work. It's not a bad way to open a movie at all. But as the movie progresses, Clark seeks more tension, more argument; the film slows and sputters.

While Bully is adults-only, it's exactly what teenagers would want to see, exactly what they're teased with in trailers for The Fast and the Furious and Crazy/Beautiful. Bully is a fantasy story of a crowd of teens who, unlike the ones in the audience, have access to drugs, money, cars and all kinds of consequence-free wild sex. How is Bully more than a meatier version of I Know What You Did Last Summer?

The acting is about the level of a slasher movie. Kelli Garner's Heather is the most authentic; she has a monologue about her demented grandfather, delivered in the half-mortified, half-amused manner authentic to a teen telling a dreadful secret. Garner transcends the limitations of this movie, just as Chloe Sevigny transcended Kids.

Bully unfolds in terms of an old drive-in movie about juvenile delinquents, because of the way Clark squares it all with the authorities: it's a protest against toxic trash culture. The Mortal Kombat video games, the porn and that bitch-bitch-bitch music turned this gang crazy, just as the juvenile delinquents of yore were inflamed to crime by Bill Haley and Fats Domino.

Here, updating of the sturdy old so-young-so-bad-so-what theme could have given the kind of cheap thrill people seek by buying true-crime books. That enjoyment, however, is impeded by Clark's pretense at avant-garde picture making, his floppy camera work, his lunch-disrupting merry-go-round cam in one circling argument--and by the eerie scenes of the doomed lovers sating themselves with sex.

There's something cheap and exploitative in Larry Clark, and I'd urge him to let it loose, because his seriousness just invites derision. At its best Bully is dirty fun, impossible to take seriously; the cities and Europe will consider Bully profound, which it profoundly isn't.

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![]()

Photograph by Tobin Yelland

Bully (Unrated: 106 min.), directed by Larry Clark, written by David McKenna and Roger Rullis, based on the book by Jim Schutze, photographed by Steve Gainer and starring Brad Renfro, Rachel Miner and Nick Stahl, opens Friday at the Towne Theatre in San Jose.

From the July 12-18, 2001 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.