![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Movies Index | Show Times | Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

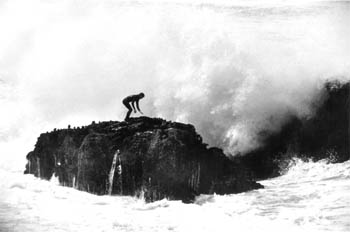

Jeff Clark had Mavericks all to himself in the beginning. Wave Action Stacy Peralta's documentary 'Riding Giants' tracks the lore and lure of big-wave surfing No one besides surfers and hydrologists really talks about the character of waves. After seeing Riding Giants—the best movie ever made about surfing, period—you can tell one roller from another. The slate-gray man killers at Mavericks on the coast north of Half Moon Bay differ from the gentle, lapping, breakwatered Santa Monica surf, fit for children to bob upon. The pure, bright blue Oahu combers, curling into that Hawaii Five-O break, evince a very different personality than the seemingly foreshortened, almost perfectly tubular roll of water of Tahiti, filmed as the grand finale of Riding Giants. In this climax, the renowned Laird Hamilton, co-producer of the documentary, mounts the Tahitian wave in a ride captured in a photo on the cover of Surfer Magazine captioned with three words: "Oh My God." After seeing Riding Giants, you can go with what interviewee Dr. Mark Renneker says: waves are more inherently interesting than the Grand Canyon, because the Grand Canyon doesn't do anything. Surfing giant waves is like having a mountain of water chasing you, explains surfer Bill Hamilton, Laird's adopted father. In Riding Giants, the act often looks like a man waltzing with Niagara Falls. Or a woman, in the case of Dr. Sarah Gerhardt of Santa Cruz, the first woman to ride the waves at Mavericks. This section of the North Coast inspires frosty respect. Few of the tourists on Highway 1 see that existentially violent water and envy the sea lion's life. The idea of getting cowled, wrapped in neoprene, entering the bristling water and trying their luck on 35-foot-tall waves is so counterintuitive that such bravado was the province of one lone surfer named Jeff Clark. Clark surfed solo for years, the only one to realize there were maximum-strength waves 20 minutes from San Francisco. Riding Giants' director Stacy Peralta interviews this pioneer surfer, who recalls life before the 1990s when Mavericks became a focus for annual competition, a sporting event alive with Zodiac boats, news crews and helicopters. Riding Giants captures the intimidation factor of these Pacific waves, with montages of boards leaping up and snapping on the rocks. Today, Clark has company from Gerhardt and others. Surfing magazine had honored Gerhardt as one of a group of surfers who had "sack," i.e., balls. Gerhardt replied diplomatically that while she appreciated the recognition, none of the other male surfers would be too happy to be congratulated for having big vaginas. There isn't a word to describe what's inside Gerhardt to make her swim her way around needle-sharp rocks, paddle out in harsh cold water for 20 minutes, spear through a steep wall of water, take her place at the top of a 35-foot-wave and ride the vertical plunge down its face. In Riding Giants, she admits, "I have to overcome my survival mechanism doing this thing that wants to kill me." Gerhardt looks like so many women one might find staring west and studying the water from Ocean Beach to Davenport; unfussy blonde hair, not particularly tall, deeply calm. She is a devotee of the ocean who's given some thought to the intangible side of surfing. "I don't just blindly go out there," she tells me. "There are times I paddle out, and I tell myself I don't have it today. It's not just about riding big waves. It's about finding out who I am. It's the mirror of truth and of finding out who God is. It's a very multidimensional experience. "My approach is different than a man's is. I think men tend to leave everything on land, and deal with the task at hand. For me it's more complicated. When there's going to be surf, I really want to do it, mind, body and soul. "

The Longest Ride The monumental juxtaposition of a tiny human figure and a 50-foot wave creates its own drama. In other surf movies, the expertise and self-assurance of the surfers make it all look too easy. The technically perfect feature film In God's Hands includes phenomenal footage of big waves photographed from below, above and inside. But the less-than-profound story line keeps punting nonsurfers out. More than any other surfing movie, Riding Giants seeks out the origin of the surfer: what it was like when there wasn't an accepted idea of who and what a surfer was. Peralta uses the same technique that he turned to skateboarding in his acclaimed documentary Dogtown and Z-Boys. The film is shot like a music video, with leapy cutting, legions of interviews, deliberately out-of-frame maps, jittery titles—a self-conscious, apologetic technique applied to a subject that has its own encyclopedias by now. Peralta's method should be exhausting but isn't. Weaving back and forth between the theory of surfing and the surfing life, he argues, "Surfing isn't something you do, it's something you become." Peralta, a man with eclectic taste in music, gives different waves their themes. Enormous waves in the opening shot are scored with the Messe Solonelle, a piece of dissonant music on horror organ, similar to the liturgical music for post-atomic mutants in Beneath the Planet of the Apes. The Bach Toccata and Fugue accompanies the first site of Mavericks. Peahi, at Maui—commonly called "Jaws"—naturally calls for the famous John Williams cello theme. And when Hamilton demonstrates how he gracefully he soars between the water and sky, Peralta breaks out some mushy Erik Satie. Riding Giants chronicles the cross-pollination of the big-wave way of life, between Hawaii and California. Peralta traces the evolution of boards. Longboards grew ever longer to make for distance swimming from the shore. Jet skis and rubber boats brought out short-board surfing. There's even a judicious discussion of the leash and its discontents.

From Wheels to Waves Peralta was old enough in the 1960s to be colonized by the look and the lore of the surfer. "That was the identity I wanted," says the 47-year-old filmmaker. "I wanted to be affiliated with them, their speech, their beach clothes, their bleached hair and tanned skin." Peralta was a skateboarder before he became a surfer. "I was skateboarding at 5, but I didn't surf until I was 11. Amazing to think I just went out there with a big clumsy board and went with a bunch of adults when I was 11, out to the jetty. I'd never let my kids do that." The success of Dogtown and Z-Boys led to Riding Giants. (Peralta's documentary about skateboarding is in the course of being fictionalized into a feature film called The Lords of Dogtown by Thirteen's director Catherine Hardwicke.) In his documentaries, Peralta has shown expertise in getting through to suspicious people. "I thought those skaters would bust my balls," Peralta jokes. "Why didn't they? They gave me so much trust. I don't know why they did, but they did." Peralta grew up in the lower-middle-class L.A. suburb of Mar Vista, near the gritty seaside towns of Venice and Ocean Park. In the 1970s, the ratty beach strip was a funk-lover's delight, with cheap unreinforced brick apartment houses, hangouts called the Oar House and Blackie's, closet-size porn theaters and broken Thunderbird pony bottles on the streets. The surfing sequences that are interspersed with the skateboarding in Dogtown and Z-Boy are, in their own way, as fierce as the big-wave action in Riding Giants. The urban surfers Peralta interviewed in his previous movie aimed their boards around the rotting, half-burnt piers of the derelict Pacific Ocean Park. The wreckage created a man-made cove, lined with jutting pieces of rebar and sharp broken wood, lying in wait for the careless. Uninviting as it was, it was a locals-only scene. San Fernando Valley surfers were sometimes pelted with showers of car parts—often ripped out of the engines of the visitors' cars. The kind of research that highlighted Dogtown and Z-Boys shows to good advantage again in Riding Giants. Peralta found out that legendary surfer Laird Hamilton was trying to work on a docudrama about "tow-in" surfing (where riders get a lift from boats to distant waves) with the French TV producer Franck Marty. Peralta, who earned a reputation in the sports-documentary world after producing 1984's The Bones Brigade Video Show about skateboarding, joined forces with Hamilton and Marty. The filmmakers cut a trailer that interested France's Studio Canal. This meant that Hamilton—a figurehead of the "40-foot-and-over" surfers, a model who'd been on the cover of GQ—wasn't the sole subject of Riding Giants. It also meant that Hamilton wasn't profiled as a surfer but as a man, with his own bio as a platinum-blond haole in a heavily native corner of Hawaii. Dozens of cinematographers were harvested for Riding Giants to shoot at the North Shore in Oahu, at one of the world's most perfect tubes in French Polynesia and ending up at Mavericks. Peralta begins Riding Giants with its roots in Hawaii, where surfing began as a sacred rite. Surfing was both a way of worship and a way of showing rank. Perhaps it still is. The missionaries, who brought the Bible and the muumuu to the islands, forbade surfing. Sol Hoopi's version of "12th Street Rag" accompanies a montage about the early-20th-century revival of surfing, a revival fed by the thousands of tourists who started flocking to Hawaii after the U.S. annexation in 1897. Sometimes Peralta has nothing but steel engravings to work with, such as an image of Capt. James Cook (the first Westerner to observe surfing). He livens up still photos with animation and 3-D picturing; in later sequences, these tricks help the audience understand the topography of the big waves. "Blind Propaganda and Hit Squad did the graphics. It's all Adobe effects," Peralta explains with a touch of awe. "I'm staggered. What's going to be possible in five years?" The extensive home movies we see in Riding Giants chronicle the life ashore as much as the life in the water. "It wasn't so much the surfing shots, but the lifestyle shots I was looking for," Peralta says. "I edited this film on my office flat-bed camera, and I had hundreds of reels of home movies to copy on a Telecine. Every 15 minutes, I was screaming, 'Eureka!' as I found another discovery." Some of the stuff Peralta found was home movies of a small group of Windansea surfers wandering through some Southern California summer in 1964 or thereabouts, who one day went to the beach in Nazi uniforms that one of their dads had picked up in the Big War as trophies. The purpose was sick-humored jackassery. ("Like turning a hearse into a surfmobile," one explains.) These kids unwittingly started the national trend in surf Nazi wear; the milder-mannered kids went with a "surfer's cross" around their necks—the Maltese cross, like the Blue Max ribbon George Peppard won in a popular war movie of the day. In surfing's ridiculous popularity, the sport fattened the Hang Ten shirt company and Jan and Dean, and spawned numberless putrid movies featuring Gidget and the Beach Party gang. The look of surfing spread to people who didn't understand the sport. It's like the recent craze for the Von Dutch tank-tops among swanky Angelenos who wouldn't have wanted to share the same elevator with the ornery, reclusive car-customizer. Particularly rare are the amateur movies of the Hot Curl Gang of the late 1940s, who hung out north of Schofield Barracks. These early North Shore surfers drove old Army-surplus cars down the dead-end roads. They packed into Quonset huts. They're seen filching pineapples from the Dole plantations, roasting a skinny, stubbly chicken on a spit and carrying speared fish out of the surf. It's no wonder surfing was such an easy life to market. In a discussion of the films that helped sell surfing to the world, Peralta includes a few words with John Milius (although, strangely, there's no mention of the cult movie Big Wednesday, Milius' mythologizing of Greg "The Bull" Noll's historic ride on a storm wave on Dec. 4, 1969). "We didn't get into surf movies later, though of course Milius created the most important portrait of a surfer in the movies, Col. Kilgore in Apocalypse Now. Milius and I go to the same cigar club. It's like sitting at the feet of the Buddha, listening to those stories." Noll, currently settled down in Crescent City, also comes out for gruff, wisecracking interviews. "He's so charismatic and so willing to share stories" Peralta said. "Getting Sarah Gerhardt in was a little more difficult." Curl Power One of the first things Gerhardt says to me is that she'd almost given up on interviews. Reporters tend to neglect the importance of Mike Gerhardt, her husband and fellow wave rider, all the better to put her in a sharp, solitary focus. While the taking or leaving of a wave is all up to her, Riding Giants demonstrates how frequently big-wave riding is a matter of teamwork; for example, in the realm of tow-in surfing, where boat pilots and lookouts keep watch. So you can imagine Gerhardt's face when she saw a profile about herself on the Fox Network's 5-4-3-2-1 show. The interview ended with an anchorman's story of how Sarah retrieved Mike from a wipeout. The newscaster winced: "Imagine being saved by your wife!" After she tells me this story, Gerhardt adds, "Mike is my partner in crime: I can count on him, and he can count on me." Gerhardt lives in Santa Cruz. She graduated last year from UC-Santa Cruz with a doctorate in chemistry. Where she grew up, inland from the Central Coast, "I didn't know about the surfer life," she says. "My best friend's mom's boyfriend was a surfer." She began surfing at Pismo Beach and Morro Bay and was drawn to Surf City mostly for the water. I asked Gerhardt if she'd heard the expression that the older you get, the more afraid you are of getting hurt, on the grounds that the young have no imagination. "My mother was a quadriplegic," she replies, "and I helped take care of her when I was growing up. So I'm aware of consequences. I'm more afraid of falling apart than being killed." She continues, "I've surfed North Shore in Hawaii and Peru. I've been around. But by far, my best year and most exciting experience have been out there at Mavericks. It's the scariest of all of them. When you think about Jeff Clark, alone out there for all those years ..." "Mavericks is surfable," Gerhardt insists. "It is large, but it doesn't crumble, though it's very fast. It's like there's a wave within a wave on top of it. And you're in it. And then you make the drop." She makes a sign with her hand, to demonstrate something like the plunging of an elevator. "It's so vertical. You have to focus, focus, focus, focus." On a day at Mavericks, Gerhardt says, "I usually last about three hours. I swim out, and it could take 20 minutes. I avoid getting creamed at the rocks they call the Gauntlet. "The improvement in wet suits over the years is startling, but women still get cold a lot faster than men. I usually get out of the water when I start feeling numb up to the hips. Dehydration actually gets you out there worse; there's no place to put water. Some of the guys will bring out water on an inflatable Zodiac boat." Gerhardt's days at Mavericks may be spectacular, but they have the same rhythms that surfing has anywhere: "You surf in the morning, break for lunch and go back for an afternoon session. And then go to the brewery in Half Moon Bay in the afternoon for group decompression." Last year, Gerhardt taught chemistry at Santa Clara University. Sometime during her commutes over Highway 17, she decided to leave SCU. She's returning to Santa Cruz for what she called "a great opportunity" to teach science at a charter high school. She can surf in the morning now, on the West Side. "I'm able to do both academia and surfing in Santa Cruz. I can start up at 5, and get a whole life in before 8 o'clock the morning." One imagines Riding Giants will inspire a lot more people to jump on a lot more boards, perhaps not the best news for the already-crowded shores at Santa Cruz. "It's a nightmare." Gerhardt admits. "The problem is that so much of surfing can be 'all about me catching a wave,' and I'm terrified of getting a board in the head." She has advice for beginners: "Go to Cowells. Go to Cowells and stay there for a couple of years, but don't go into the lane. I've had a few near misses there; people can't maneuver. They get in top of me and start yelling. There's a huge unwritten, unspoken etiquette of surfing it would take you 10 years to learn."

Spiritual Side I don't surf, but I used to ride a belly board at Balboa in Orange County. I'm well aware of what's its like to spend a day in the ocean—to be pulled backward, held in the grip of a wave. The push and pull of it remains inside you after you're home in bed. Surfing isn't an experience that easy to write about or describe. Gerhardt says that talking about surfing is like putting any other spiritual experience into words. Laird Hamilton says simply, "It softens some hard corner in my life." Sam George, Riding Giants' co-scriptwriter, comments in the film, "They don't say 'religious bum' about a person who tries to get into the spiritual." He means that it's a slander to describe people who devote themselves to the eternal and ineffable power of the surf as "beach bums." Doesn't the surf have the divine capability of conveying grace and exhilaration? Or the potential to absent itself without warning: the surfers here speak of their misery when the surf's flat and their purpose for living is suddenly withdrawn. Like God, as God is understood, the surf can be destructive, dealing out death without warning. What the surf teaches may be best conveyed through watchfulness and silence—it's clear why so many surfers are so taciturn. Challenging this silence as it does, Riding Giants opens up new lines of inquiry into this enviable way of life.

Riding Giants (PG-13; 102 min.), a documentary by Stacy Peralta, opens Friday at selected theaters.

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com. [ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

|

From the July 14-20, 2004 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.