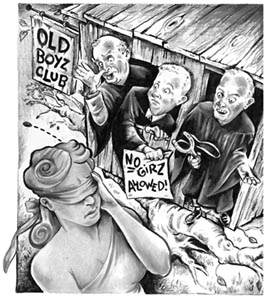

The Boys on the Bench

In apparent violation of ethical canons, several local judges hold secret memberships to San Jose's oldest good-old-boys club

By Will Harper

The High Sierra resort town of Graeagle (pronounced "Gray Eagle") Meadows in Plumas County attracts thousands of tourists each year who come to drain its lakes of trout and monopolize tee times at one of its championship 18-hole golf courses.

Among the tourists sucking up the mountain air one weekend last month were 90 of the most prominent men in Silicon Valley. Among them were VIPs like Sheriff Chuck Gillingham, Democratic congressional candidate Jerry Estruth and Palo Alto public relations executive David Oke. (District Attorney George Kennedy, a regular attendee, couldn't make it this year.)

The powerful vacationers were in Graeagle for the annual retreat of Los Pescadores de San Jose--the San Jose Fishermen--there to cast off the responsibilities of public service while they cast a line and hit the links.

Los Pescadores, the subject of a recent article in The Recorder, a Bay Area legal paper, is billed by its own as "the oldest men's club in San Jose." It arose about 70 years ago from murky beginnings that even club members claim not to know about. Whatever its roots, the club is now dominated by white men in law enforcement and public safety--judges, prosecutors, cops and firefighters--though several businessmen also claim membership.

There are no women in the club. There are no rules barring women from joining, members say. But women are also not being recruited either, which effectively keeps them out since membership is by invitation only.

Some members argue that women probably wouldn't want to join the club anyway. And maybe they wouldn't. Around the Hall of Justice, female judges and attorneys privately roll their eyes when they hear about the Pescadors' alleged affinity for boozing, cussing and carousing.

Peter Carter, co-owner of the public relations firm Carter & Israel, recalls being invited to one of the Pescadores dinners a few years ago at Bini's Bar & Grill. The soiree featured lots of joke-telling. "The jokes weren't the kind you would say in front of female company," says Carter, who didn't join the club.

While even old-school fraternal organizations like the Elks Lodge the Rotary Club now include women in their ranks, the Pescadores--as those in the know call the organization--have managed to reserve their activities for bearers of Y-chromosomes. That kind of operation was typical when the club formed 70 years ago, but according to some critics, it is more than just politically incorrect, at least for the judges in the club.

Judicial canons now prohibit jurists from joining or participating in clubs that discriminate "invidiously," legalese meaning groups that discriminate on the basis or race, creed or gender. Judges can be disciplined by the Commission on Judicial Performance--possibly even removed from the bench--for breaking the canons or rules.

At least eight judges here are either club members or have gone on outings with the Pescadors: Superior Court jurists Robert Ahern, John Ball, Daniel Creed, Thomas Hastings (who presided over the Richard Allen Davis trial) and Hugh Mullin; and Municipal Court judges Ray Cunningham, Leon Fox, and Ed Pearce.

Alameda County Municipal Court Judge Julie Conger, a veteran of the California Judges Association's ethics committee, says that based upon what she's heard Los Pescadores fits the description of a club that crosses the ethical line for judges.

"It seems to me that because this club has no women, appears never to have had any women or ever offered a membership to any woman, it invidiously discriminates," she says.

The Boys Are Back

BECOMING A MEMBER of Los Pescadores isn't like joining the YMCA. According to sheriff's Sgt. Jim Arata, a Pescador since about 1995, an existing member must sponsor a new member for two years. If a pledge is invited back a second time to the annual retreat, he's in the club.

Despite its aura of back-slapping informality, the club has a board of directors and a president who help convene get-togethers. Judge Ahern and Judge Creed have both previously served as the group's Grand Poobah.

Nonetheless, the few Pescadores willing to talk about the club insist it's nothing more than a casual organization and accuse critics of telling fish stories about its exploits.

Judge Ed Pearce, who acknowledges having attended the club's outings, reluctantly offers that, "If I go fishing with four guys, I don't think the Commission on Judicial Performance will find a problem with that."

Judge John Ball, the club's most outspoken defender in the judiciary, says that despite having a board of directors, the club has no bylaws or secret handshakes, though the guys enjoy an occasional cigar or beer. "It's just a group of individuals that enjoy camaraderie [and] golf and fishing," he maintains.

Los Pescadores holds three events each year, including the annual fishing retreat in the mountains, a dinner get-together and a tournament at Santa Teresa Golf Club.

Ball insists that the club doesn't discriminate and never has denied membership because of gender or race. He says he knows of no women who have expressed an interest in joining.

Several other members say they can't recall ever inviting a woman to join. (Municipal Court Judge Jamie Jacobs-May says Judge Cunningham once invited her to a Pescadores dinner, but quickly adds she doesn't think it was "a serious invitation.")

Ball allows that it may have simply never occurred to anyone in the club that women would want to tag along. "It's not a men's club; it's just that the activities we participate in most women are not interested in doing," Ball argues.

Fish Stories

THE FACT THAT THE CLUB has no female members isn't the only thing about Los Pescadores that gets lawyers talking about judicial propriety. The clubby relationship between member judges and attorneys also has some concerned.

Shortly after returning from this year's trip to Graeagle, two Pescadores found themselves in the same courtroom, but on different sides of the bench. Judge Ball was sitting in on a case being handled by Deputy District Attorney James Shore, a fellow member. Ball, however, didn't disclose their mutual affiliation to the opposing attorney.

According to the California Code of Judicial Ethics, judges must disclose for the record "information that the judge believes the parties or their lawyers might consider relevant to the question of disqualification, even if the judge believes there is no actual basis for disqualification."

The idea of the rule is to give lawyers a chance to ask for an unquestionably impartial judge to ensure fair treatment of their clients.

A judge who spent a weekend with a prosecutor trading stories about the one that got away might, according to the disclosure rule, feel compelled to 'fess up to a defense attorney facing off with that prosecutor.

"On something that's a close call," observes a prominent San Jose attorney who asked not to be named, "who's [the judge] going to favor--someone who's his fishing buddy or a Joe Blow attorney he doesn't know?"

But Ball doesn't think disclosure is required when a Pescador appears before him. Neither he nor any of the other judges could accurately describe any of the prosecutors in the club--there are at least five including Kennedy--as "fishing buddies," Ball says.

According to Ball, judges tend to hang out with other judges during the club's weekend retreat and interact sparingly with prosecutors or attorneys who may appear in their courts later on. Judges scrupulously avoid discussing cases and don't have any more contact with attorneys than they would have at a Bar Association event, he adds.

A dozen or so judges contacted for this story were reluctant to say whether Pescador judges should disclose their club affiliation in court. Many agree that this is a gray area, though some, like Judge Conger, say they prefer to err on the side of caution. (Conger says she regularly discloses her relationship to a lawyer who sits on a nonprofit board with her and with whom she dines once a month.) Local Superior Court Judge Gregory Ward says he tries to avoid such questions by belonging to as few organizations as possible.

According to judicial canons, judges must not only avoid conflicts of interest or impropriety, they must avoid the mere appearance of conflict of interest or impropriety. "The rules change if you're a judge," explains Superior Court Judge LaDoris Cordell, who teaches ethics to new members of the bench. "Our conduct is more closely regulated than regular people."

Some local female attorneys and judges privately observe that for their male colleagues to be in an all-men's club at the very least looks bad.

And one well-known San Jose lawyer familiar with the Pescadores says it disturbs her that the same judges participating in this men's club are the same people enforcing gender-discrimination laws.

In addition to feeling excluded from the Pescadores "boy's club" of fishing and golfing, evidence exists that some women believe there is a hostile work environment overall in the superior courts. Last year county clerk Steve Love sent employees to a sensitivity-training course after a male court-facilities manager, now retired, made comments at an awards ceremony about a woman being late because she was too busy putting on her makeup.

Longtime court clerk Alice Shore filed a lawsuit two weeks ago against the county, accusing administrators of ignoring her complaints about a court contractor who allegedly verbally abused and groped her. County officials say they responded appropriately and investigated Shore's complaints. (Shore is the wife of the aforementioned prosecutor James Shore, a member of Los Pescadores.)

There is also, however, evidence that Pescadores are not all chauvinist pigs at work. Pescador Sheriff Chuck Gillingham in 1990 made Assistant Sheriff Laurie Smith one of the highest-ranking female law enforcement officials in the state. And women make up about half the division leaders in District Attorney George Kennedy's office.

But, once again, the standards for judges are different: They must be beyond reproach, the saying goes.

Judge Cordell remarks that, in general, if judges are part of a club that excludes women, and if judges fudge disclosure rules, that worries her.

"If something like that actually exists, I'm concerned because I'm part of the system, and something like that can hurt public perception of the judiciary," Cordell says. "It harms the judiciary, it harms the process. It harms all of us."

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Illustration by Terri Groat-Ellner

From the July 23-29, 1998 issue of Metro.

![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)