![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Casinos in Cyberspace

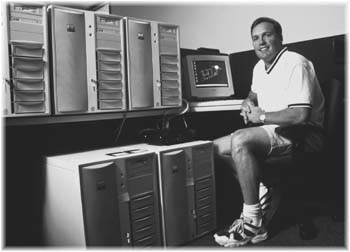

Net Profitable: Mark Waters found a way to make the Web pay with a virtual casino where visitors gamble with 'funbucks.'

Gambling on the Internet could become an $8 billion industry by the year 2000, with a hot new Sunnyvale company leading the way--unless a spate of new laws drives the action off-line

By Robert Struckman

I GET INTO NETSCAPE, type "www.funscape.com" and wait. The words "Casino Royale" appear as the Internet gambling site loads. I click on "Open Account" and type in my name, address and Visa card information, signing up for $50. After being approved, I receive my account password, click on "Enter Casino," and I'm in--playing blackjack for Funbucks.

Within 20 minutes I lose $42.76 in real American money. I've played 40 hands of blackjack and 10 slots, and taken one spin on the roulette wheel. The "wheel" is set up like a keno screen, with rows of boxes and numbers; when I click on "spin," the screen disappears, and when it reloads, I lose. It's too boring to do again.

Blackjack is just like regular blackjack, except that, again, I lose, lose and lose--the dealer wins 27 out of 40 hands.

Casino Royale, which is based in Sunnyvale, is the only online gambling operation currently operating in the United States. Mark Waters, director of business development at the company that runs the online casino, is ecstatic about his company's prospects. "The profit margin is incredible," Waters says. "We run the same odds with none of the cost. It really is amazing."

Whatever Waters' company, Handa-Lopez Inc., picks up from hapless blackjack players is icing on the cake. HLI makes Internet gambling software and markets packages of hardware and software to companies in the Caribbean and Asia. The complete packages retail from a quarter-million dollars to half a million, Waters says, and HLI has sold 10 since early May.

According to Waters' own estimates, HLI is the world's largest vendor of gambling software and servers. Their clientele spans the globe and, like the X-rated industry, the company is on the front edge of Internet commerce--and raking in the bucks.

This is an industry whose future would seem to be perilous: While police, state attorneys general and gambling organizers agree that offshore Internet gambling is in a legal gray zone, onshore gambling is clearly illegal--even in cyberspace.

Several lawyers helped HLI establish the casino as a contest, Waters says. He is confident that gambling for "Funbucks"--some of which are available free--is not within the purview of state or federal law. So he is unashamed.

"I'm not going to kid anyone," he says. "This is the same action as in a casino. We started it to basically run some advertising [for the company's Internet gambling packages], but it was so successful we just kept running it."

Matt Ross, of the California Attorney General's office, refuses to speculate about the Casino Royale site, but says the fake-money idea is a ruse.

"The use of 'funbucks' is no different from Nevada casinos that use their own currency for their machines--redeemable, of course, for U.S. dollars," he says. "House-banked card games like poker--and blackjack is specifically mentioned--are clearly illegal."

Maverick Nerds

IN A MINI-MALL ON Evelyn Street in Sunnyvale, Waters stands next to the receptionist's desk and launches into what sounds like a typical Silicon Valley conversation:

"Ideally you have these four kick-ass servers, which stack up two and two. It's a dual Intel system, totally redundant, so it never goes down. The top end costs half a million dollars. But that's nothing compared to what you'll make.

Waters is a standard-issue South Bay resident: young, ambitious and employed in the high-tech industry. Handa-Lopez Inc. is a standard small-scale company. HLI has 20 bright-eyed employees, brand-new office space and plenty of enthusiasm about the future.

"I think, optimistically, that we could be a $100 million company by the end of the year," Waters says.

A lot of people recognize this profit potential. Internet gambling is a mushrooming industry.

In January, 15 sites were in operation, mostly from the Caribbean. Since then, that number has doubled. Experts predict that it may double again by the end of the year, and some predict that it will be an $8 billion industry by 2000.

At the front of the pack in the run for gambling cyberbucks are sports-booking enterprises. Experts say that sports booking is the fastest-growing segment of Internet gaming because there is less room for cheating--the betting lines are public, and everyone knows who won and lost the game.

Beyond questions of legality, the idea of online gambling might sound crazy. Would you send your Visa account number to an online bookie?

Trust, an important issue in Internet commerce, is a difficult thing to gauge with gambling. Gambling experts say that the trust issue will determine whether online casinos ever hope to win more than a tiny share of the $550 billion spent on legalized gambling annually.

Anti-gambling organizations say they doubt the ability of the services to mollify the customers' worries. But the gamblers themselves tell a different story, especially where sports gambling is concerned. Sports gamblers in the Bay Area say that online action is more reliable--and less sleazy--than what can be found through bookies.

In a two-story brick office building in Emeryville, about a mile from the Oakland side of the Bay Bridge, Jay Cohen, who co-owns a highly regarded sports gambling site on the Internet, sits in front of a computer. The office houses the public relations company for World Sports Exchange, which operates from St. Johns in Antigua.

Cohen left a job as a market maker on the Pacific Stock Exchange in San Francisco about nine months ago to set up a sports book with Steve Schillinger, also of San Francisco.

The World Sports Exchange's Web site, www.wsex.com, is a simple, no-frills sports-gamblers' heaven. The site has three windows with plain white backgrounds, black text and no graphics to speak of. On the left is an index, on top is basic information about the site, and on the right is a listing of everything an American sports fanatic would want to gamble on.

Experts say sites such as wsex.com could eclipse the sex industry as the Web's largest money-makers. The culture of sports gambling on the Internet is affected by the same principles that govern all online commerce. Fringe businesses abound because they are less scummy on screen than in real life.

Political Gamble

AMERICANS bet about $85 billion last year on sports, according to gambling industry estimates. Cohen estimates that such noncasino-going gamblers are flocking to sports betting on the Internet. For that reason, sports gambling is a special concern for lawmakers and gambling opponents.

Sue Schneider is co-founder of Rolling Good Times On-line, an Internet gambling e-zine, and is the chairperson of the Interactive Gaming Council, an online gambling industry group. She and others are preparing to bring some self-regulation to the industry.

"We're meeting the 26th of July to develop a review board," she says. "Basically, regulation is coming to online gambling."

Meanwhile, federal and state governments are sorting out their policies. State and federal legislatures are adding Internet references to anti-interstate gambling acts already on the books. But many people agree that the new medium operates beyond standard methods of regulation and control.

Predictions of the final legal outcome vary. But Bernard Horn, communications director of the National Coalition Against Legalized Gambling, says the nation is in a window of opportunity between the invention of a new crime and federal measures to stamp it out.

"The U.S. could put these guys out of business in the blink of an eye, just by putting international warrants out for their arrests," he says of online bookmakers.

Tim Leslie, a Republican state senator from northeastern California, introduced a bill to the senate's public safety committee on May 6 to make it illegal to use the Internet to gamble. Other states, such as Missouri and Minnesota, have taken the issue on, often by expanding old anti-gambling statutes. The National Association of U.S. Attorneys General issued a recent report backing the efforts of the states and federal government to ban Internet gambling.

And Sen. Dianne Feinstein co-sponsored the Internet Gambling Prohibition Act of 1997. The bill would make Internet gambling punishable by up to a year in prison and a $5,000 fine. It requires the Justice Department report on the extent of computer gambling by this time next year--the first comprehensive study ever of online gaming.

Cohen says that the nature of the borderless Internet makes most of these methods of policing inadequate.

"I think it will come down to the location of the server. No country can police the world. The laws governing the location of the server should have jurisdiction over the happenings on a site."

That would leave the sites in the Caribbean free to operate, but cause trouble for operators like Mark Waters.

Last week, Waters says, he met for several hours in Sunnyvale with a group of Eastern Europeans. He says HLI sold them a system for more than $500,000 on July 16.

Even if the United States puts firm resolve behind outlawing Internet gambling, Waters says, HLI will probably continue to sell its servers. And HLI has plans to expand.

"We don't have the resources yet to set up sports gambling sites," Waters says, "but we're going to meet with a guy from out in Nebraska who's been setting up sports book programs. It would be good to link up with him.

"This is just the tip of the iceberg," he says, laughing at himself and adding, "I've been saying that for years. But it is. It really is. This is just the tip."

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

Christopher Gardner

From the July 24-30, 1997 issue of Metro.