![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Movies Index | Show Times | Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

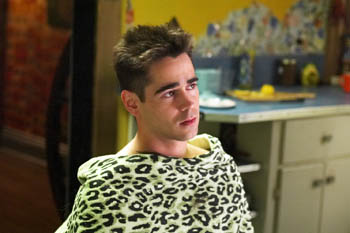

Photograph by Rafy Growing Up Is Hard To Do: Young Bobby (Colin Farrell) contemplates his growing responsibilities. Two Men and A Baby Colin Farrell looks for 'A Home at the End of the World' CERTAIN PEOPLE live in a state of grace. They may not be deeply intelligent, but they're deeply intuitive. In the movies, such passive, graceful people appear infrequently, and they are rarely approved of. The few examples that come to mind are Élodie Bouchez in The Dreamlife of Angels and Tom Hanks in Forrest Gump. A Home at the End of the World is about a slightly drug-addled Clevelander named Bobby (played in adulthood by Colin Farrell) who drifts from the summery 1960s into the latitudes of the frosty 1980s. This is Farrell's first really important performance, playing an overgrown kid whose honesty, loyalty and good heart save him from oblivion. Based on a novel by Michael Cunningham (The Hours), the film begins when Bobby, a kid from a negligent household, shares a tab of windowpane LSD with his beloved older brother. Together, they trip in the cemetery on the other side of the wall of their backyard. "My son, this is your inheritance," declares his brother, drugged and lordly. But the graveyard consumes Bobby's home, one family member at a time. At high school, Bobby meets his friend for life, Jonathan (Dallas Roberts), over a joint; he moves in with the kid, and they live like brothers with the blessing of his mother (Sissy Spacek). Why do the movies ration Spacek out in such small portions? The episode of her getting high with her son and his friend is one of the year's highlights. While the three dance together to Laura Nyro's "It's Gonna Take a Miracle," different tensions, particularly sexual ones, float in and out of the room. Later, Spacek has a few lines about how getting married narrows your world. It would have been the overemphasized big moment of truth in a lesser movie; here the truth's nodded at as the movie passes by. In Manhattan, Jonathan comes out of the closet. Bobby trades in his black shag for an angular haircut and gets a rose tattoo for his shoulder; and he takes to punk rock as enthusiastically as he took to Nyro's singing. Farrell is as lusciously handsome as Antonio Banderas was in his Almodovar movies—he's a man so available that he's still a virgin, and he's so passive that he has never really learned how to make the first move. Bobby and Jonathan are content to live side by side, but a woman in their lives insists on progress. Clare (Robin Wright Penn) is a bundle of nerves, topped with fire-engine-orange hair. She insists on a child and insists on limits. A Home at the Edge of the World looses its grip, because Penn—with her unattractive anxiety—steers the film into thirtysomething hokiness. The three friends visit the Grand Canyon and move into a small town outside of Woodstock and buy a genteel cafe; it's a montage of newly embraced responsibility after the things of youth are set aside. And the movie ends on a sprawl of different endings, in favor of the stark, the snow-covered and the serious. What I longed for was to see Bobby continuing his easy ways, still drawn by that invisible current of grace, as the rest of us just muddle through.

A Home at the End of the World (R; 95 min.), directed by Michael Mayer, written by Michael Cunningham, photographed by Enrique Chediak and starring Colin Farrell and Sissy Spacek, opens Friday at Camera 12 in San Jose.

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com. [ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

|

From the July 28-August 3, 2004 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.