![[Metroactive Arts]](/arts/gifs/art468.gif)

[ Arts Index | Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

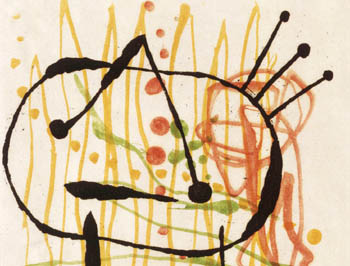

Art or Scrawl?: Miro's 1957 intaglio 'La Bague d'Auror' poses a puzzle at the Cantor's new show. Picture Puzzles An interactive show at the Cantor Arts Center raises a 'Question' or two about what makes art By Michael S. Gant I TEND to like my museums the way I like my coffee: dark, bitter and a bit haughty. In other words: low lighting, gilt frames, crusty coats of crackling varnish, some taciturn guards in thick-soled work shoes and clutches of guidebook-toters dutifully admiring the art of the ages because, after all, it's in a museum. Obviously, I'm out of step with the times (in many, many ways), and my Platonic form really only applies to Old World museums-as-mortuaries like the Louvre, the Prado and the Hermitage—temples of received culture depending upon an aura of absolute authority to justify their existence. "Question," the new show at Stanford's Cantor Arts Center, wants to shake up the traditional notions of a museum's function. Instead of anointing a single artist or genre, "Question" offers a wide range of art objects in provocative contexts and coupled with a variety of interactive tools. Based on a project by the museum's curators and students, the show seeks to answer—or at least acknowledge openly—the kinds of queries that the museum's patrons often raise about what they see. In some instances, the questions are easily addressed. A Dürer engraving of The Virgin and Child With a Monkey is contrasted with a facsimile version. Close inspection reveals differences in paper, clarity and ink color; lift up a hinged card, and you can have your suspicions confirmed about which one will turn a profit at auction. Similar displays provide useful information about how museums go about authenticating unsigned artifacts. The show moves onto slippery ground when it grapples with the thornier notion of what constitutes "good" art. The unknown artist of Christ Blessing the Children produced the kind of high-toned religious kitsch that drains its subject of any possible emotional resonance, but what are we to make of Charles Christian Nahl's 1875 Spanish Girl With Bird? At first, the image of a stereotypically coy courtesan looks slick and weightless, but after a while, it starts to seduce the eye as effectively as any hyperrealist exercise. Cycles of taste matter, too. Nahl's painting, like the once abused, now "discovered anew" Orientalist fantasies of the Victorian era, could be due for a re-evaluation any day now. Some pieces stand alone without need of any of the occasionally overly gimmicky interpretive apparatuses (which include voice-overs, viewer-controlled lighting and labyrinthlike layout). Rembrandt's little etching Star of the King draws the viewer in with a glowing star lantern that emerges from an ocean-deep darkness; only after careful study do the figures celebrating the Feast of the Epiphany resolve themselves from the dense line work. Just as powerful are two Goya etchings: a plate from Ravages of War depicting a welter of brutalized bodies, and On Account of a Knife showing a garroted priest trussed to a pole. The direct questions posed can quickly lead to some metaquestions. Why is it that museums are suddenly so intent on finding new ways to package their permanent collections (the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, for instance, recently unveiled a "reinstallation" of a chunk of its holdings)? Funding cutbacks and the spiraling cost of traveling shows have forced curators into such creative exercises. And the visitor wondering about institutional context should contemplate the Cantor's minishrine to the Stanford family, the fons et origo of the campus. Thomas Hill's Palo Alto Spring with the Stanfords at a formal picnic, a black servant in the middle ground and a statue of a Native American farther back, speaks volumes about the railroad magnate's place in the state's history. Even better is A.D.M. Cooper's Jewel Collection, a showcase of Mrs. Stanford's baubles set against a red-velvet backdrop. Leland's widow wanted a record of her gems before she sold them off to raise funds for the university's library—an odd conjunction of robber baronism and philanthropy made even odder by the wall label, which mentions that a copy of the painting ended up in a gambling saloon in San Jose.

Question runs through Jan. 2, 2005, at the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford. (650.723.4177)

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com. [ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

|

From the July 28-August 3, 2004 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.