![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Tiger By The Tale

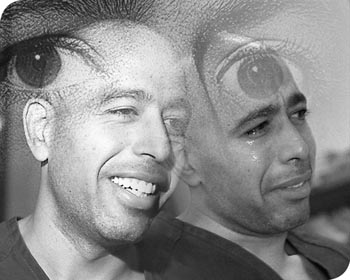

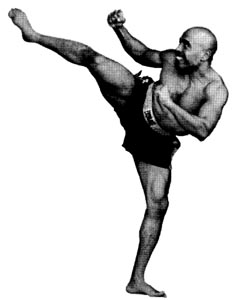

Photographs and montage by Christopher Gardner When Los Gatos police officers arrested David Slavin in front of his west San Jose home last month, he had $240,000 in cash in his trunk, two guns, two picture IDs and an assortment of wealthy friends and ex-friends. The mysterious lives and multiple personalities of a man who called himself the 'Immortal Tiger.' By Jim Rendon DAVID SLAVIN APOLOGIZES. He has not had a chance to shave today. A light stubble clings to the round top of his head and down the long stretch of his cheeks. The guards only allow him to shave in the middle of the night, he explains, and there are perils to shaving one's own head when half awake. The smile he cracks brings his whole face to life, and his upper body stretches with his grin, but his arms hang limply at his side. Only occasionally, when he tries to scratch an itch on his face or, later, wipe away tears, do his hands rise up above the table top, straining against the chains linking his wrists to his waist, flashing a silvery glint into the otherwise institutionally dull jailhouse reading room. Slavin has been on the second floor of the Santa Clara County Main Jail on Hedding Street since June 4. At 7:30 that morning, Slavin was planning to take his son to school and his wife to work. Still half asleep, wearing only his slippers, sweat pants and a T-shirt, Slavin heard a noise behind him in the driveway and turned to face the barrel of a gun. Los Gatos SWAT team officers forced him and his 13-year-old son to the ground in front of his home. "I thought I was still dreaming, still sleeping. Then eventually I heard my wife crying, and my son crying," Slavin says, his voice trailing off. Slavin's son was taken away by the county's child protective services, two weeks before his graduation from middle school. Slavin and his wife, Elizabeth, were taken to the county jail for booking. Then officers searched his home, his post office boxes and his Subaru sedan. "I've seen violent felons with priors arrested in a different manner," Slavin says. "For whatever reason, I was not treated fairly. I do not blame the officers who came in and arrested me, I blame the process, the information given to them." In the trunk of his car, investigators found a gym bag stuffed with cash--$240,000 in bills. In the house they found a shotgun and a handgun--both legally registered--boxes of paperwork including bank statements that they thought might be related to the allegations against him, and identification cards which proved that Slavin had two separate identities. Since he was arrested, the 37-year-old former sheriff's deputy, martial artist and kick-boxing instructor has shrunk. The bulky arms that in publicity photos were creased with muscle have withered beneath a brown prison top. The face that once bore a theatrically menacing look in his newspaper ads, daring anyone to try to beat him in a martial arts fight for $100,000, looks lackluster and withdrawn. He wears red jail-issue pants instead of the standard orange, marking him as someone facing serious charges, as a prisoner who is potentially dangerous. Fearing that he would flee the country, the court has denied him bail. But Slavin speaks softly, deferentially addressing guards as "Sir." He talks about how his arrest has damaged his family, destroyed his relationship with his son. He says his God will not let him be angry--that he must find another way to face up to his incarceration and the decades of prison time he may face. And he cries openly. That is exactly how Slavin's alleged victims said he would act: humble, charismatic and credible. For the past five years, Slavin has taught martial arts and kick boxing at gyms and studios across the west side of the valley, including Courtside in Los Gatos. Some students are vocal defenders of Slavin and say he preached a nonviolent morality, that he was generous and always concerned about others. One student even put up a $100,000 bond to bail Slavin's wife out of jail. But Mary Lean, a wealthy student of his at Courtside, says that while he was impressing the other students, he was extorting cash from her--$240,000 to be exact, along with $1 million in promissory notes which he tried to blackmail her into paying by using a sexually explicit videotape. Other former associates say Slavin muscled his way into a Los Gatos martial arts studio, Studio Kicks, and then held a samurai sword over the fingers of one of the owners to get him to sign a promissory note for $70,000. To some Slavin was the enlightened Japanese Full Contact Association World Champion, and the only American master of Ti-Fi, a Japanese martial art. To others he was the Brooklyn-born street fighter who maintained a network of Mafia connections, including a menacing godfather-type figure named Nicoli Pacini, who later turned out to be Slavin in a wig and glasses. Since his arraignment in federal court, attorneys and investigators familiar with the case keep talking about more victims and more charges that may soon be leveled against the man who called himself the Immortal Tiger, who convinced people to give him promissory notes totaling millions of dollars. Slavin's defenders say the government has little hard evidence beyond the word of victims. His attorney, Thomas Salciccia, thinks his client may be the victim of a conspiracy between the Los Gatos Police Department and prominent members of that community. "This kind of case is very uncommon," says Los Gatos Police Detective Randy Bishop, who began investigating Slavin in March of 1998 after receiving reports that Slavin had threatened to cut off a martial arts instructor's fingers with a samurai sword. By that fall, Bishop began working with federal Internal Revenue Service investigators who had begun their own separate investigation into Slavin's business activities. "It's not every day that you find $240,000 in the trunk of a car of an aerobics instructor," he says and then pauses. "This is going deeper than anyone expected."

INSIDE THE WOOD-FLOORED aerobics room in Studio Kicks, a martial arts studio in a strip mall at the edge of downtown Los Gatos, instructor Larry Lam is standing on tiptoe. He swings his arms in tight curlicue punches, the way a third-grader on the playground would berate someone for having a girl's punch. "That's how he punched," Lam says with a laugh. "He really didn't know martial arts." Lam has starred as Leonardo in the second and third Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle movies and he acts in TV shows as well. But he also loves teaching and has worked hard to turn Studio Kicks into what he calls one of the best martial arts studios in the country. He recalls that Slavin first showed up at Studio Kicks in the mid 1990s when his son began taking classes there. Initially, there was no reason to think twice about Slavin, Lam's former partner, Rick Donaldson, says. Slavin was married and had great son. He ran a business in Saratoga that he said sold police and military equipment, and he taught at prominent athletic clubs in the valley. He was friendly and talkative. At the studio, Slavin talked a lot about his martial arts background. He claimed to be the only master of Ti-Fi (rhymes with hi-fi) outside of Japan, and the highest ranking master of the form. He also claimed to be the Japanese Full Contact Association's World Champion. Slavin began to brag about his background, saying he had once killed a man in Japan, demanding recognition and respect, Lam says. When Lam organized an exhibition, he says, Slavin wanted his name at the top of the flier, despite the prominent crowd of martial artists on the list. At the exhibition, Donaldson watched Slavin break two Louisville Sluggers in half with his shin. "He's a little taller than me, and he said he was trained in fighting, not 'sport karate' like me," Donaldson says. "I wouldn't mess with him." Despite Slavin's abilities, Lam says that Slavin knew that his martial arts background alone was not enough to intimidate anyone in his studio. He began bragging about his Italian-American upbringing on the mean streets of Brooklyn, where disputes were decided with fists and guns, where respect was paid to tough guys with connections. Lam says Slavin told him that he "owned people" in city government, construction and other businesses. And he often carried a gym bag full of cash. In the fall of 1997, Lam and Donaldson mentioned to Slavin that they were a little short on rent. Without hesitation, Slavin offered them $30,000 cash, no questions asked. The partners took it. In return, Slavin asked if he could use the studio to teach his own brand of aerobic kick boxing on nights and weekends. The partners agreed. Before they knew what was happening, Slavin was remodeling one of the rooms in the studio. He ignored their repeated requests for an estimate or receipts, saying it would all be taken care of. Slavin invited Donaldson and Lam to lunch in Saratoga when the work was finished. He pushed two pieces of paper across the table at them, promissory notes for $70,000, payable to Nicoli Pacini. Pacini was a godfather-like figure who funded his business ventures, Slavin said. He wanted each of them to sign a note as insurance, so that if something happened to one of them, the other would still be liable for the money, he said. Lam and his partner refused to sign. They had never seen any receipts for the work Slavin did and figured he could not have spent more than $15,000 on the room. Pacini's name had not come up before, and they didn't appreciate Slavin's veiled threat. But soon, Slavin convinced them to change their minds. On Nov. 6, prosecutors say, David Slavin called two men into the office at Studio Kicks. He closed the door, drew the blinds and then once again placed promissory notes for $70,000 in front of each of them. Sign the notes, he urged. Without waiting for a response, he unsheathed the samurai sword displayed on the desk and pinned Rick Donaldson's hand to the desktop. Placing the blade across Donaldson's fingers, Slavin asked them again to sign the promissory notes. Feeling the steel against his fingers, Donaldson agreed. "I was thinking, will he cut my fingers off? I realized he probably would." The next day Lam and Donaldson went with Slavin to a notary public and signed. Since they were singing under duress, the two figured that the notes were not valid. It seemed like an easy way to placate Slavin without letting this strange dispute disrupt the business they had worked so hard to build. Slavin began to have a bodyguard show up at the studio and stand around in a trench coat while he taught his classes. And Slavin began to brag that he had worked as a hit man. When Donaldson left the country and Lam went out of town on a film shoot, Slavin changed the locks and began depositing money from the business into his own accounts. Lam looked at it as a way to quickly pay back the $30,000 loan and get him out the door, with little fuss. But in March of 1998, when Donaldson returned from South Africa, Slavin insisted on meeting the two in a local park. As he talked, urging Donaldson to sign over his portion of the business, he held a pouch slung across his chest as if it contained a gun, Lam says. But Donaldson refused to give up his place in the business. It was then that the two went to police and had Slavin escorted from the studio and Detective Bishop began to look into Slavin. Not long after that, two men in trench coats and sunglasses showed up at Studio Kicks and told the partners it would be a good idea to take Slavin back. One person even called and put them on notice that Slavin had asked him to break Donaldson's legs. As Slavin's increasingly strange behavior began to escalate, Lam says he began to doubt how much martial arts training Slavin really had. No one had ever heard of Ti-Fi or the Japanese Full Contact Association. And it would be easy to just make up an organization and claim to be the world champion. From what Lam saw of Slavin in his classes, the man was certainly nowhere near the level of some of the top Ultimate Fighters who live in the Bay Area. Nonetheless, after being banished from Studio Kicks, Slavin ran an ad in Metro in July 1998, offering $100,000 for anyone who would come forward to challenge him for the Japanese Full Contact Association title. Brian Johnston, a retired Ultimate Fighter who trains in San Jose and is now a Japanese professional wrestler, saw the ad. "That ad kind of bugged my ego a little bit," Johnston says. "I don't mind if the guy has been somewhere and done something, but this is like me saying I'm a professional race car driver when I've never actually sat in a car before." When Johnston returned to Japan in 1998, he did some background research on Slavin, but he turned up little. He could find no form of fighting called Ti-Fi, and no records of Slavin fighting there. "I found nothing," he says, recalling his surprise at the time. "No one knew him."

Slavin, he says, is a great guy and an excellent teacher. "When I first started taking his class, I thought I had no aptitude. But David has such a great personality--everyone thinks so. I'd take his class no matter what he was teaching." Knapp gets up and demonstrates what Slavin teaches. Knapp swings his arms, each in an upper cut, then turns, swings a kick, then blocks, then turns and kicks again. There are a few lengthy series of movements that are strung together and then set to music, he explains. It's challenging and a lot of fun. But more than his style of exercise, Knapp was drawn to Slavin's personality. He would stay after class and philosophize about current events or explain his own nonviolent ethics, Knapp says. Slavin was opposed to any kind of abuse of authority or power, and warned people to never use martial arts outside of the classroom unless it was for self-defense. "There was no way he had ever been a threat to any of us. I would invite him into my home or to see my family without hesitation. He never asked anything of me. He was the most polite guy I'd ever seen," Knapp says, more than a little outraged at the charges that have been leveled at his teacher. While Slavin has been accused of taking advantage of the wealthy people he brought close to him through his classes, Knapp says Slavin had every opportunity to victimize him and nothing ever came of it. He even discussed opening a fitness club with Slavin, but Slavin never pursued it, never tried in any way to take advantage of him. "There is a possibility I can't see it," Knapp says, considering that maybe he too has been taken in by Slavin. "But I'm a pretty good judge of character and I know when people are BSing me. When I visited him in jail, he looked me straight in the eye and said, 'I've got boxes of evidence to refute this.' " Knapp is so convinced of Slavin's innocence that he put up $100,000 of his own money to get Slavin's wife, Elizabeth, out of jail. She has been charged with conspiring with her husband in some of his crimes. Others in Knapp's Courtside class agree that something is not right. Slavin often took students to lunch and always insisted that he cover the bill. He volunteered at his son's school and brought healthy foods, like vegetable spread, into class for his students to share. None of them can understand how this benevolent man could be guilty of extorting money from anyone. "Those of us who work out with him are baffled, completely," says Regina Teeter, a student of Slavin's at Courtside. But one of Slavin's students at Courtside says she knew a very different person in David Slavin, a person she is willing to spend a half-million dollars to put behind bars for a very long time.

MARY LEAN, a youthful-looking 49-year-old Asian woman with straight black hair cut into a bob, alternates her attention from the floor at her feet to the end of hallway outside a federal courtroom in San Jose. Though Lean has filed a civil suit against Slavin seeking $240,000 that she says Slavin extorted from her, and her case is one of those that the federal government is bringing against Slavin, her name has been kept out of both the federal indictment and the newspapers. But Lean has sued Slavin in civil court, making her name and her allegations public. She alleges that she was scammed, much like Lam and Donaldson were, but for more money and perhaps in a more cruel manner. Through her attorney, Mel Honowitz, she has refused to speak to Metro or to provide Metro with her written responses to questions submitted to her in June. But her allegations, if true, are a far more damning indictment of Slavin than anything he may have done to Lam and Donaldson. Lean met Slavin at Courtside athletic club in February 1998, when she began taking his aerobic kick-boxing class. Soon, according to Lean's suit, the two became friends and began working out together. By May, she says, the two were having an affair. As the relationship became more intimate, the couple began talking about opening a high-end exercise studio in Los Gatos. But before signing any paperwork, looking for a space or really discussing plans in any detail, Slavin told Lean he had bought $1.6 million worth of exercise equipment. Lean, he said, should give him a million dollars as a good-faith deposit on their future business together. When she refused, according to her suit, Slavin said that his underworld friends were funding the business venture and that if she didn't start paying him money, they could both be hurt. In a matter of days, the pressure paid off. Lean gave him $44,000 in cash. The following week, she gave him a cashier's check for $156,000. When she asked for receipts for the money, he refused. Instead, he gave her a receipt for $200,000 indicating she had paid for "specialized training." In September, Slavin told Lean over lunch that he and his partners did business with notes. He explained that she need not worry, that he only needed her signature on a few things for tax purposes. After lunch, she says in her suit, he took her to an ATM, where he showed her a recent wire transfer into an account for $307,000 from someone he says he threatened to rough up. Over the next few days, Lean signed two notes, one for $800,000 and another for $200,000, putting her a million dollars in debt to Slavin. She says that Slavin continued to pressure her for more money, and some weeks called her almost daily. The threats, which before were directed at the two of them, were now directed at Lean. If she didn't pay, he told her, he would send two guys to beat her up. On Sept. 24, Lean paid Slavin another $40,000. Some women in Slavin's class say that the instructor has a certain allure, that he is the kind of guy women go for, which may help to explain why after giving Slavin $240,000 and signing away an additional million following veiled threats, Lean baked Slavin a birthday cake on Oct. 5. After the class, she says, Slavin asked Lean for another birthday present. In a hot tub spa, where Slavin allegedly rented a room for an hour, Lean says she was talked into making a sexually explicit video. In her lawsuit, Lean says that Slavin promised to give her the tape, but once it was made, he refused. The tape became leverage for more financial pressure, she claims. That fall, he asked her for $1.3 million to participate in a $100 million Eastern European heavy equipment deal. If she refused, he would distribute the sex video, he told her. Two months later, Lean got a restraining order and filed her suit against Slavin. Honowitz is disgusted by what Slavin did to his client and what he may have done to others. "The man is a viper," he says. To other students, the case is much less clear-cut. Knapp took classes with Slavin for two years and was in the same class as Lean. Yet he says he had never even noticed Lean before. Regina Teeter, another student in the class, recalls that when she missed the cake that Lean had baked for Slavin's birthday, Lean "jumped all over" her for it and appeared more upset than made sense. She also recalls that last year Slavin announced during one of his classes that he was being harassed. He asked whoever was leaving threatening notes on his car to stop it, that he was married and not interested. His wife, Elizabeth, often attended his classes at Courtside throughout the 18 months he taught there, including the time that he was allegedly sleeping with Lean. According to documents related to the civil case, Lean does not work, but lives off a trust fund, and, like Slavin, has many names that she has used--five in all. She graduated from Los Gatos High School and then went to college for two years at Oregon State University. In the 1980s and throughout the 1990s, Lean went to school almost continually, taking courses at Santa Clara University, West Valley College, the California Culinary Academy and Le Cordon Bleu in Paris. Since Slavin was arrested and Lean filed her lawsuit, Teeter says Lean has been pestering people at Courtside for personal information so she can subpoena them for her civil case against Slavin. Lean's attorney, Honowitz, has been relentlessly aggressive about nailing Slavin, making sure that no lead goes unfollowed. To help out, Honowitz brought the king among San Francisco private investigators on board--Jack Palladino.

According to the articles, Palladino has himself been accused of strong-arm tactics, from his work for the Clinton campaign in 1992, where he was accused by Dick Morris of silencing women who allegedly had affairs with Clinton, to his efforts on behalf of Courtney Love to suppress an unflattering book about her role in Kurt Cobain's death. Palladino says that he spent seven months conducting an international investigation of Slavin at the request of Mary Lean and that Lean's family has spent nearly a half a million dollars preparing their lawsuit, twice as much as she is suing Slavin for. Since very early in his investigation, Palladino has been sharing his findings with the federal investigators. "Slavin has seen too many action movies," Palladino says. "He's trying to be the last action hero." Larry Wallerstein, the attorney representing Slavin in his civil case, questions why Palladino and Honowitz have spent more money putting this case together than Lean is suing for. The pair have already bullied two attorneys away from Slavin's defense against the lawsuit. Wallerstein, who has known Slavin for years, is also passing the case on. He says Slavin needs a civil attorney who knows more about criminal law. Palladino and Honowitz claim that they and Lean's family want to nail Slavin so badly because he is a predator and a bully. He's a professional who has spent decades developing his cons and may well have decades' worth of victims in the shadows waiting to come forward. According to Palladino's lengthy investigation, Slavin was born in Palo Alto on Oct. 5, 1961, as Mohamed Elnemr. His parents were from Egypt, and Slavin's father was in graduate school at Stanford when David was born. While Slavin tells some people that his father is Italian and his mother is Filipino, and that he grew up in Brooklyn, Palladino says his best guess is that Slavin grew up abroad and lived in Cairo in the early 1980s. In 1985, Slavin went to work for the Santa Clara County Sheriff's Department, assigned to the jail, but that job was short-lived. According to court documents in the criminal case against Slavin, in September 1987 Slavin beat up an inmate for telling a racist joke. Later, Slavin allegedly asked another jail worker to lie about the incident and say that the man physically threatened Slavin. The case resulted in a hung jury and was dropped. Slavin left the sheriff's department in 1987. In the mid 1980s, Slavin officially changed his name, Palladino says. He shed the name Mohamed Elnemr for David Slavin. And according to the federal affidavit for the search warrant on Slavin's home, it turns out Slavin has another name. Nicoli Pacini, Slavin's "godfather" figure, has Slavin's thumb print, on file at the DMV. Though Pacini has a Social Security card and driver's license, the picture on the license appears to be Slavin in a large afro wig and glasses. During the late 1980s and early 1990s, Palladino could not determine what Slavin did for a living, but he seemed to have easy access to large amounts of cash. Slavin was involved in multiple real-estate transactions. Many of these, Palladino believes, were fraudulent schemes in which Slavin took advantage of people of limited means. Slavin, meanwhile, says he was just maintaining sound business standards. "If you don't make payments, eventually the bank will say, 'Pay or we take the car,' he says. "That's the way it's done." Between 1987 and 1997, Slavin owned five pieces of property in the valley, two of which he sold outright. But the other three houses were sold, repossessed and then sold again, possibly netting him tens of thousands of dollars. One participant in a real-estate deal was his own sister-in-law, Carolyn Tinoco. In October 1991, Slavin sold his wife's sister and her husband, John and Carolyn Tinoco, a home in San Jose. According to a lawsuit filed by the Tinocos, they agreed to take over the mortgage and to pay Slavin an additional $66,500, payable to Slavin over five years with no interest. But when Slavin presented them with the agreement to sign, it said that the full sum was due at any time and that the Tinocos owed Slavin $554 a month in interest. When they asked about the discrepancy, Slavin said not to worry and that he would stick to the verbal agreement. But it was only a matter of time before Slavin called in his note and tried to foreclose on the property. The Tinocos sued, and in the end the judge required that Slavin write a new contract, adhering to his original verbal offer. In 1996, the Tinocos filed for bankruptcy and Slavin repossessed the house. Just a few months later, he sold the property again. Palladino says that the Tinocos are terrified of Slavin and do not want to come forward. Other people who bought and lost property from Slavin are no longer living in the county. Palladino says that the federal government is busy investigating these transactions to see if more victims of these schemes are willing to come forward. Jeff Nedrow, the United States attorney prosecuting Slavin, refused to comment on what direction the continuing investigation is taking. But not everyone sees these transactions as damaging. As long as Slavin did not misrepresent himself, there is nothing illegal or unethical about helping people to buy homes in this way, Wallerstein says. Some people might even consider it a helpful, generous thing to do.

"I was going to open my own studio by myself and I was approached by some people to do it a different way. As a consequence, I am here right now," he says glancing down at his handcuffs. But he will not elaborate on what happened between the time he was approached and when he landed in jail. He says even less about Mary Lean. When asked whether he had a sexual relationship with her, Slavin cracks a wide-mouthed laugh but refuses to answer directly. "She was a student who was eager to learn; she came to all different classes. She wanted to be in the areas that I was in," he says. "I have nothing bad to say about anybody." And where did this kick-boxing instructor get $240,000 in cash? Slavin and his attorney say the money is legitimate, and the government knows it. His attorney, Thomas Salciccia, says the money comes from an insurance claim, but that is all they will reveal. Slavin told people at Studio Kicks that his Saratoga home had been destroyed by an arson fire, but neither Slavin nor Salciccia will confirm that this was the source of his money. Though investigators found Slavin with large amounts of cash, Salciccia points out that there is no law against using a gym bag instead of a bank account. All of Slavin's victims signed notes declaring their debts in front of a notary public. Why they signed boils down to a he saidshe said argument, hardly enough for a criminal prosecution, his defenders say. But Slavin refuses to answer many of the most perplexing questions about this case. When I ask more about his relationship with Mary Lean, his supposed Mafia connections or why he had two identities, Salciccia halts him. With other questions, Slavin looks to Salciccia for guidance. The concern, his attorney says, is giving his defense strategy away to the prosecution months before the trial. But there are many basic questions that Slavin refuses to answer, like where he learned martial arts, where he was born and even where he grew up. When I ask him about his ethnicity, all he will say is "I am an American." He talks at length about how his family has been treated unfairly, because they are different, though he won't specify how they are different. For all Salciccia's hinting at a grand conspiracy, Slavin does not outwardly exhibit the outrage of a framed man, or the anger of someone who ended up on the bad side of a misunderstanding. If Slavin is guilty of even some of what he accused of, he may spend decades in a federal prison uniform. But when I ask directly if he is innocent, he hedges on the question for a moment. Then, head buried in his chest, a muffled "Yes" emerges. When Slavin's trial begins in September, he will face six counts of extortion, two counts of money laundering, and two charges related to using his mother's Social Security number on a bank account. At that time, investigators and attorneys will try to reveal the truth about the personas of David Slavin, whether he is really the enlightened Courtside instructor, or the volatile underworld figure from Studio Kicks, or just a con artist who started to believe his own lies. [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the July 29-August 4, 1999 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 1999 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.

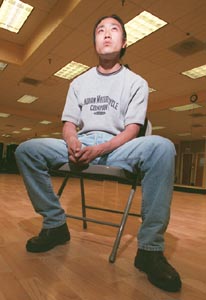

SITTING ON THE DECK overlooking tennis courts and the shimmering aqua-blue reflections of the swimming pool at the Decathlon Club in San Jose, Ron Knapp explains that this is the place where he first met David Slavin two years ago. Knapp, 47, is a tall, thin, gray-haired semi-retired engineer. Despite his wiry physique, Knapp is a calming person, quiet, thoughtful, not the kind to jump to conclusions.

SITTING ON THE DECK overlooking tennis courts and the shimmering aqua-blue reflections of the swimming pool at the Decathlon Club in San Jose, Ron Knapp explains that this is the place where he first met David Slavin two years ago. Knapp, 47, is a tall, thin, gray-haired semi-retired engineer. Despite his wiry physique, Knapp is a calming person, quiet, thoughtful, not the kind to jump to conclusions.

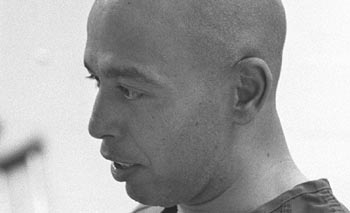

Swift Kick: Larry Lam says he and his partner, Rick Donaldson, had Slavin barred from their martial arts studio, Studio Kicks, after he threatened violence to get them to pay $70,000.

Swift Kick: Larry Lam says he and his partner, Rick Donaldson, had Slavin barred from their martial arts studio, Studio Kicks, after he threatened violence to get them to pay $70,000.

PALLADINO PREFACES HIS conversation with a press kit about himself, containing a company bio, clips and a San Francisco Examiner Magazine cover story about him.

PALLADINO PREFACES HIS conversation with a press kit about himself, containing a company bio, clips and a San Francisco Examiner Magazine cover story about him.

BENEATH THE FLUORESCENT lights of the triangular jailhouse reading room, Slavin answers a few of the allegations against him. Though he's vague, he tries to address what happened with Larry Lam.

BENEATH THE FLUORESCENT lights of the triangular jailhouse reading room, Slavin answers a few of the allegations against him. Though he's vague, he tries to address what happened with Larry Lam.