![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Get a Job!

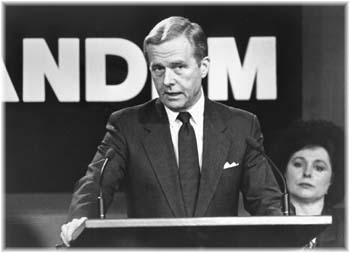

George Sakkestad Executive Decision: Gov. Pete Wilson resisted Assembly Democrats' efforts at progressive reform. After 20 years of political squabbling, California lawmakers have crafted a welfare reform bill that could find work for a half-million people. But some folks are being left out of this new deal. By Eric Johnson TIM COMSTOCK, the press liaison for Gov. Pete Wilson's health and welfare department, is trying his best to explain what's going on down the hall from his office. This involves some fancy crystal-ball-gazing. The issues around welfare reform are complex, five reform bills are dead, and the political winds seem to be shifting every day. The governor is unavailable for comment, and the first-string spin doctors are tied up talking to the L.A. Times and potential swing-voting Republican lawmakers. When pressed, Comstock is willing to cough up some quotes. He knows the story about as well as anyone outside the small room where the Big Five--the governor and the leaders of both houses--have been locked in negotiation for the past week. He insists that the historic agreement taking shape will, in fact, work. "It's not going to be easy," he concedes. "We're talking about a huge social change. But we've gotta have faith that in our society, if this is shown to be heartless, if people are getting screwed, then we'll do something to make it right." During 15 minutes of conversation, the Wilson administration's press flack maintains his upbeat tone. Despite all the uncertainty, despite 20 years of partisan rancor--which isn't over yet--he is optimistic. Of course, it's Comstock's job to be upbeat. What's startling is that everyone familiar with this issue, including liberal Democrats and advocates for the poor, have the same sound in their voices: hope. The numerous press reports that depict a hard-hearted Wilson administration beating back a fervid Democrat-controlled Assembly are not entirely false. When the governor vetoed the bill that came out of a bipartisan committee two weeks ago, he attacked Democrats for sending him a package of bills that "perpetuate a gravely flawed system that discourages work and encourages welfare dependency." Apparently, he said, the package had been "crafted by the most overzealous of welfare-rights advocates." In theory, the dispute remains deep and bitter. But it does not really take up that much legislative territory. Dozens of interviews conducted over the past two weeks reveal that on most of the key questions, local representatives from both parties, as well as the Democratic and Republican leadership, are in agreement. As this story goes to press, with the assembly entering the final week of work before summer break, there is reason to believe that California lawmakers may soon unlock a stalemate that has polarized and paralyzed the state for two decades.

A Closer Look: Democrats like San Jose Assemblyman John Vasconcellos conceded that welfare needed reform, and searched for a progressive solution. SANDY BROWN of the Campaign for Budget Fairness, which advocates for low-income people, says the process that brought the Big Five together last week was a good one. "The negotiations produced a rational and realistic policy choice," Brown says. But as the eleventh hour, she says, things began to get ugly: "After Pete Wilson's veto of the conference committee vote, the process was undermined. It was turned into a political game. Discussions became very partisan in nature." San Jose Republican Assemblyman Jim Cuneen defends the Governor's veto, because, he says, the conference committee bill was weak on work requirements and time limits. "The Democrat proposal was riddled with exemptions," Cuneen says. "If we're going to adopt meaningful legislation in California that is consistent with federal guidelines, we need to make sure that the incentives are solid." But Cuneen adopts what once would have been considered hard-core liberal language when talking about the intent of a reformed welfare policy. "We have an opportunity to fundamentally rethink the way we provide compassionate assistance to people who are down on their luck," he says. San Jose Democratic State Senator John Vasconcellos agrees that the welfare system didn't work, but he insists that people on welfare need jobs more than they need legally mandated incentives. Vasconcellos points out that poverty, in California, mostly affects single women with children. "We've been told by the federal government that we have to find jobs for 500,000 women with children in the next five years," Vasconcellos says. "By and large, these woman are not trained to perform the kind of work that would allow them to support their families. "Even if they were," he adds, "there aren't enough jobs available. Even with the current robust economy, California produces around 350,000 new jobs a year at most. "And if the jobs were there, there are no child-care slots to put all the kids." Many welfare recipients also face mundane yet crippling barriers such as lack of transportation, while some have substance abuse problems or suffer from mental illness. If some version of AB 1501 survives the week, it will almost certainly contain funding to deal with many of those needs. At press time, the bill on the table provides money to put 425,000 welfare recipients into the GAIN training program by 1999--that's 275,000 more than can take part in the program now. It creates 120,000 new child-care openings this year, and possibly another 100,000 next year. (The bill assumes, somehow, that the rest of the 230,000 kids living in families now on welfare will be able to stay with their grandparents or neighbors.) It also provides for substance abuse treatment, mental health counseling and help for victims of domestic violence. All good, according to Sandy Brown. But meaningless, unless there is work available for these people. "When you get down to it, this whole problem is really about job availability," Brown says. "The 'welfare-to-work' plan really has to be about creating jobs, because there aren't enough out there." "When Republicans spend all their time talking about responsibility and incentives, and when the governor gets up there and accuses these people of being unwilling to work, that's insulting." HARSH RHETORIC has dominated the welfare discussion ever since Ronald Reagan launched the reform crusade almost 20 years ago, shortly before leaving Sacramento for Washington. Reagan termed the welfare system "the worst economic mess since the Great Depression," and introduced the terms of debate which have persisted to this day. Railing against "welfare cheats," he decried welfare dependency and demanded personal responsibility. Democrats responded by refusing to even concede that the issue was worth debating. While they acknowledged that the welfare system wasn't working, they attacked the new breed of Republicans as class bigots engaged in a massive act of blaming the victims. For two decades, the parties battled to an impasse. The words "welfare reform" were uttered in every single national political campaign, but nothing much was done. The debate created an army of Reagan Republicans: working-class people who felt they were being ripped off by lazy poor people. It also had a social repercussions, deepening racial and class divisions. Then Bill Clinton came along. And then Newt Gingrich. When the president signed the 1996 Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act, he fulfilled Ronald Reagan's vision--forced to do so by the Army of Gingrich. Clinton even stole a line, standing in the Rose Garden and declaring "an end to welfare as we know it." But looking at some parts of AB 1501, Clinton's decision to embrace welfare reform almost looks like one of those kung-fu moves where the black belt uses his opponent's attack to trip him up. Maybe, by going with the consensus that had built up around welfare reform, the president absorbed its force in order to gain an advantage. The job-creation portion of the proposed reform legislation, which has been virtually ignored in the press, revives a version of Clinton's 1992 economic stimulation proposal. According to sources close to the Big Five budget negotiations, this $470 million jobs program is not a sticking point in the negotiations. While Democrats are angling to allow legal immigrants to collect food stamps and Supplemental Security money, and while Wilson and the Republicans are pushing for firmer work-requirement deadlines, the jobs idea appears to be safe. THE WELFARE-TO-WORK program is made up of 22 separate components. Many would cost nothing--for instance, one calls for retired CEOs to lobby business leaders to hire welfare recipients. But four of the proposals involve public financing of jobs. The current bill contains an investment fund that would provide $25 million and an infrastructure bank that would provide another $50 million so counties could hire people to build bridges and staff libraries. There is another $40 million fund to send working Californians back to college so their entry-level jobs will become available, and a $5 million "micro-enterprise" fund to allow welfare recipients a shot at entrepreneurship. But while those look like hard-core Democrat proposals along the lines of the New Deal and the New Society, the most ambitious program contains a healthy dose of Reagan-era cooperation with big business. The $350 million Linked Deposit Fund shifts some of the state's deposits to private companies so they will hire and train welfare recipients. Cuneen is less than enthusiastic about the jobs-creation package--in fact, in an interview last week, he insisted that it was an issue separate from welfare reform. He is firm in his belief that the main thing welfare recipients need is to know without a doubt that they must get a job. "Often, they make a lifetime out of going through the motions of looking for a job, but never quite finding a job," he says. "We have to tell these people that we'll help, but you're going to have to contribute. This is going to require a physical act of responsibility, of getting up in the morning and having to do something." Even though he takes issue with some of the particulars, Cuneen says he believes a compromise will be crafted out of the Democratic proposal. This is partly thanks to his moderate-Republican fiscal sensitivity. If California doesn't put something together in the very near future, the state will lose $190 million of federal money. Gov. Wilson faces that hard reality--and two Democratic houses--with a scant 34 percent approval rating. According to Fred Keeley, Santa Cruz's Democratic assemblyman, that means California will probably get a welfare reform bill--perhaps even before this article goes to print. Vasconcellos spent the past week shuttling between Sacramento and Southern California, where he and other Democratic legislators met with business leaders in Los Angeles and San Diego. He says the jobs-creation package is essential if welfare reform is going to work. "When it comes down to really trying to get at the root of the problem, it's all about giving people real opportunities to get meaningful work," Vasconcellos says. "This is about more than just jobs; it's about dignity. This way they'll gain, and we all will, too." [ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.