![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Movies Index | Show Times | San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

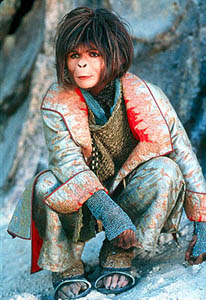

Chimp and Still Champion: Helena Bonham Carter keeps the series alive in the new 'Planet of the Apes.'

Chimp and Still Champion: Helena Bonham Carter keeps the series alive in the new 'Planet of the Apes.'

The Ape Chronicles From Charlton Heston to Tim Burton, the monkey-suit saga shows no signs of running down

"What is the ape to man? A laughing stock or a painful embarrassment ... once you were apes, and even now man is more of an ape than any ape." --Nietzsche, Thus Spake Zarathustra WHEN CHARLTON HESTON appears on television doing interviews about the Planet of the Apes series, he's fond of pronouncing the 1968 classic as "the first space opera." But the other important trend Planet of the Apes launched was the merciless use of the sequel. The constant sequels were as essential to '70s kitsch as John Travolta's pompadour. The original Planet spawned four sequels, a mediocre TV show and an even more mediocre series, Back to the Planet of the Apes, woven from the first program; and last, the animated Return to the Planet of the Apes finished the run, until Tim Burton got ahold of it for this summer's blockbuster remake. (This list ignores Stop the Planet of the Apes, I Want to Get Off, the fictional musical starring Troy McClure on The Simpsons: "I hate every chimp I see, from chimp-pan-a to chimp-pan-zee/No, you'll never make a monkey out of me.") As the British novelist Will Self described it, what made the Planet of the Apes franchise unique was the way it explored "the alternate pathways of time ... the idea of worlds that mutate off of our own." The Apes films make a loop in which the talking apes have no real origin. Apparently, the ape race begins and ends with Zira (Kim Hunter) and Cornelius (Roddy McDowall), who escape Earth's second and final nuclear holocaust. They travel back in time via spaceship to Earth in 1973 (Escape From the Planet of the Apes, 1971) thus becoming their own grandparents. It's hard to resent this artful storytelling. COMING UP with a sequel to Beneath the Planet of the Apes (1970), the second film in the series, represents a great moment in the annals of writing for hire. Beneath the Planet of the Apes ends with the detonation of a cobalt bomb destroying all life on the planet. Write a next act for that! Critiqued for its opportunism and its cheapjackness, Beneath the Planet of the Apes also starred James Franciscus (without whom there could be no Troy McClure). But from a first-run viewing of Beneath the Planet of the Apes at the Skyway Drive-In outside Seminole, Okla., I'd judge the sequel more interesting than the original. The viewing conditions were perfect: only dirt roads led to this remote "ozoner," which meant arriving by battle-scarred pickup truck in a postapocalyptic cloud of red dust. When I finally got to Burning Man decades later, I'd been prepped for it. The money shots in Beneath the Planet of the Apes are the Forbidden Zone hallucinations of the year 3955: a battlefield full of upside-down, flaming, crucified gorillas; the colossal statue of the Lawgiver weeping tears of blood and toppling with a crash. The final battle takes place after a religious ceremony. It's the high mass of the masked mutants, and the Doomsday Bomb is praised by an atonal choir. (Quite the shock for a kid who'd never previously heard anything more musically dissonant than Tex Ritter.) The experience certainly stole the thunder from Salvador Dali and Luis Buñel's surrealistic classic Andalusian Dog when I saw it later in college. And the subtext was plain even in Seminole. Beneath the Planet of the Apes' ad campaign paraphrased Abraham Lincoln: "Can a planet long endure half human and half ape?" It was a question much asked in America in 1970, depending whether one's definition of "ape" was "longhaired, yellow-bellied hippie" or "Pentagon baby killer." The Shakespearean actors aboard the series aided the operatic scope of the series. What good would Shakespearean training be to a person playing a monkey? Answer: studying Shakespeare teaches an actor how to plumb great wells of feeling, even when dressed ridiculously. The Planet of the Apes films starred Maurice Evans, as the pompous orangutan Zaius. Evans was a ripe old capital-T thespian; his 1960 film version of Macbeth is stodgy enough to deject the most serious Bard-lover. Roddy McDowall, who co-starred with Evans in The Tempest on TV in 1960, returned to the series' bitter end as the rebel ape Caesar in the 1972 Conquest of the Planet of the Apes. Heston himself had been starring in Shakespeare films since a 1950 made-in-Chicago 16mm version of Julius Caesar; you can see the Shakespearean rage in Heston's most famous roared-out soliloquy: "Oh, my God. I'm back. I'm home. All the time. We finally really did it. You maniacs! You blew it up! Goddamn you! Goddamn you all to hell." Let's round up the other films: 1971's Escape From the Planet of the Apes was a money-saver filmed in Beverly Hills and San Pedro. A conniving U.S. president plots to kill the time-traveling Zira and Cornelius, while the adorable quips fly thick and fast between the couple. The much better Conquest of the Planet of the Apes (1972) is Spartacus in a gorilla suit: in 1990 "when life is computerized and controlled," enslaved apes are rallied by McDowall's Caesar. An interesting plot device whizzes by: Cornelius and Zira bring with them a plague that kills off all the world's dogs and cats (an idea pinched from Philip K. Dick's 1968 Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?) The movie's other big idea was filming in the then-new, still-alienating Century City complex, a mini-Brasilia in West L.A., built on the bulldozed Fox studios. The night battle scenes in this metropolis of skyscrapers still keep their futurism 30 years later. Battle for the Planet of the Apes (1973) was The Longest Ape Day, with both ape and mutants blasting each other with WWII vintage equipment; it's a lofty snooze, despite John Huston aped out as that ape-messiah the Lawgiver. The Shakespearean elements were gone, and the tale had become too convoluted to allow the Cold War or the Civil Rights movement to give it reflected depth. Memories of how much ape-pimping 20th Century Fox did should be balanced by stressing how risky the original was. Most studios had passed on it, unable to think of an outer-space story as anything but serial fodder, cheap and silly. DURING THE ARDUOUS filming of the first Planet of the Apes, Heston told director Franklin Schaffner, "I thought from the beginning we'd have a hit, but we may have a helluva picture too." Certainly it was a hit. Mostly, it was the technique that sold the film, the wonderful ape makeup that cost $1 million in 1967 money; with 200 artists hired to transform the actors. (John Chambers, who won an honorary Oscar for the original Planet of the Apes makeup, had been an ex-prosthetic maker for the military, replacing missing ears and noses.) The most fun in watching the new Tim Burton Planet of the Apes is in seeing how well Rick Baker has improved on Chambers' work. If only the script were up to it! The genocidal monkeys, parodying the human politicians, are once again a part of the story's joke--though the gorilla fascists in Planet of the Apes 2001 are caricatures of extinct ultraconservatives. Laughing at them is safe. A better sort of script for the remake would have likened the gorillas to today's politicians--making them superficially kind and gentle on the human issue. If only the gorilla leaders been more devious and given to double-talk, speechifying their concern for protecting humans and their families, while capturing them in safety nets. Now, the question is, will Burton do the right thing and remake Beneath the Planet of the Apes? [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the August 2-8, 2001 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 2001 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.