![[Metroactive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Reflections on A Golden Movie

A British critic dreams about the movie with the Midas touch

A British critic dreams about the movie with the Midas touch

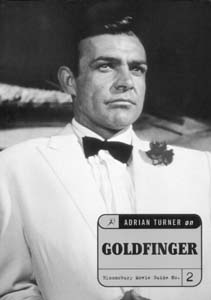

FOR YEARS, I was trying to write a short story about a boy whose mother won't tell him how he was fathered. One night, the mother and son are watching the James Bond film Goldfinger on television. During the assault on Fort Knox, some soldiers are betrayed by the villain Goldfinger. They're fooled by his fake military uniform and shot in the back with bullets from his gold-plated pistol. When an anonymous extra in an Army uniform falls over dead, the mother shakes her son's arm, saying, "That's him! That was your father." As the child grows older and more suspicious, the mother polishes the lie. What she meant to say, she tells him, was that the actor was playing the boy's real-life father, shot during the defense of Fort Knox. His father's killer was the real-life criminal, the source for the fictional Auric Goldfinger. For years, the boy believed that there was a secret history of the United States, and that part of that history was James Bond, even if that wasn't his actual name--that there was truth to the fantastic story of a European Midas who loved only gold, who had an atomic bomb and a chauffeur named Oddjob who could crush a golf balls in one fist, that all of them lived outside the realm of a movie. The critic Adrian Turner's book Adrian Turner on Goldfinger understands that sense of a larger existence that some movies take on. The volume is a harmonious blend of fact, interviews, reviews and reveries. It's a labor of love, this study of the third James Bond picture--one of the biggest hits of the 1960s, the cornerstone of the world's most popular film franchise. Turner attended the premiere of Goldfinger at the Odeon Theater in London's Leicester Square on Sept. 17, 1964. (The publicists claimed that the print arrived in gold-plated film cans.) The author balances his endless fascination with 007 with an appropriately saturnine attitude toward the snobbishness, sexism and all-around un-PCness of Ian Fleming's Commander Bond. (As fans know, Sean Connery's deadpan playboy of the same name is a different creature, a wonderful cross between Buster Keaton and Cary Grant.) Turner writes with a lack of pretension and much amusement. His book is funny, as befits a study of a film that was, among other things, a new breed of cruel comedy. Adrian Turner on Goldfinger is organized as a glossary, with entries from A to Z. Central to the study is a warm interview with Goldfinger's director, Guy Hamilton. Hamilton is retired now, but his career-long second-stringness is demonstrated by his reputation as the best assistant director in British cinema. It was Hamilton who decorated the barren shrubs of Africa with wads of Kleenex colored with stage blood so that there would seem to be lilies blooming in the backgrounds of The African Queen. As assistant to director Carol Reed, Hamilton captured all the misshapen Viennese faces in the night scenes of The Third Man. THE HAMILTON INTERVIEW is supplemented with short essays on everything from the history of the Aston-Martin company to the career of Ken Adam, Goldfinger's stainless-steel-fancying production designer. Turner also met with golden girl Shirley Eaton, asking her whether she had objected to being photographed nude, gilded from head to foot. (Actual Eaton quote: "I didn't mind as long as it was done tastefully.") Here, also, is a dossier on one Erno Goldfinger (190287), an architect who loved the color, the texture, the divine heaviness of reinforced concrete. With his public housing towers, Erno Goldfinger did his part to make London hideous. In fact, Fleming himself once protested Erno's modernist housing developments in Hampstead Heath. The notes on Goldfinger's heavy, Gert Frobe, are more thorough than those in any previous study of the Bond films, and God knows I've read them all. Goldfinger was Frobe's obituary role, so to speak. Yet the actor almost didn't get it; the avuncular folksinger Theo Bikel was a first (and really weird) choice. Critic Lotte Eisner once described Frobe as "the scum of the German film industry." This scum sounds like a nice guy. On the set, Frobe used to beguile his fellow actors with his one-man band routine, complete with cymbals tied around his belly. I loved Adrian Turner on Goldfinger for its anecdotes, though his knowledge of other spy films seems to be sketchy. In a list of films inspired by Goldfinger, he claims that Lee J. Cobb was the villain in the Our Man Flint series, when in fact Cobb was superagent Derek Flint's boss. And I disagree with Turner's judgment of the scenes in which the kidnapped Bond (Sean Connery) is, uh, bonding with Goldfinger in Kentucky. Calling these moments "awkward," Turner fails to appreciate the paternal rapport of our hero and our villain. They banter like a light comedy team. Goldfinger proudly shows his English prisoner a racehorse that he's just purchased, and Bond mutters, "Better bred than his owner." The cheerful mood of these moments is what makes Goldfinger an elegant game. In the original draft of Richard Maibaum's script, Goldfinger confesses that he likes Bond. The line was dropped, but wasn't Goldfinger a sport to let Bond live? After all, he had 007 as surely as 007 ever had been had--all nicely strapped down and with a laser beam aimed squarely at his balls. Turner's study is influenced by the master critic David Thomson's A Biographical Dictionary of Film, as well as by Suspects, Thomson's marvelous set of fictions based on the imaginary extra-cinematic lives of movie characters. Turner, for instance, has a theory about the later days of Pussy Galore, a lesbian whose mind was changed by 007. (She's played in the film by the tender yet acerbic Honor Blackman.) In an item titled "Scarlet Letter, The," Turner spins a story of how Galore became the wife of Mark Rutland, the rich brute Connery played in Hitchcock's Marnie. Plausible, and certainly touching. Me, I think Bond was just an experiment for Pussy Galore. Even the most dedicated lesbians have their occasional male flings--after all, Sappho is supposed to have killed herself over a male boatman. Shouldn't even waste time wondering, really. But my own passion for Goldfinger has survived many years and many viewings. The last entry in Turner's book is "Z--Zeitgeist," which he references as "all of the above." Certainly this bizarre, beloved film did sum up the spirit of its times. Goldfinger prepared an audience for future shock in the pleasantest way. The film was an instant lesson in pop art and paranoia. It presented a vision of a world full of tough women, martial arts and crashing music--all of which has come to pass. Goldfinger's brashness invigorated children and intellectuals alike, creating a new genre: the out-of-this-world spy film. In 1964, the usually vinegary critic Penelope Houston wrote that Bond was "the first of the joke supermen." Since Goldfinger, movie screens have been trampled by legions of joke Supermen, playing onscreen even as I write in the varied forms of Will Smith's Jim West and Mike Myers' Austin Powers. None--sadly--displays the elan, the sleekness, the humor of Connery's 007 in Goldfinger. P.S.: The real Fort Knox Depository stands on a weedy, rocky hillock, right next to a busy two-lane highway. As Turner notes, not even the president is allowed inside. Visitors, like I was, are shuffled over to the adjacent Patton Museum of Cavalry and Armor, whose hangars shield a fine collection of tanks, some of the general's pistols and several panels of the Berlin Wall. In a dusty corner stands a plastic display case about the size of a card table. The case holds a small model of the Fort Knox Federal Depository donated by Guy Hamilton. The model was used in the Rumpus Room scene in Goldfinger. Interior: Frobe's Goldfinger, using the model as a goal--as a goad--for his fellow villains, is orating before a gathering of the heads of America's criminal families. (Only Michael Corleone of Lake Tahoe was wise enough not to attend, Turner writes.) "Man has climbed Everest," Goldfinger declares. "Gone to the bottom of the ocean. He has fired rockets to the moon. Split the atom. Achieved miracles in every field of human endeavor. Except crime!" James Bond himself, hiding beneath his nemesis's inner sanctum, peeks through this model's windows, spying on Auric Goldfinger. None of Patton's tanks are as substantial as this piece of a dream. Adrian Turner on Goldfinger By Adrian Turner Bloomsbury; 250 pages; $15.95 [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the August 5-11, 1999 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 1999 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.