![[Metroactive Arts]](/arts/gifs/art468.gif)

![[Metroactive Arts]](/arts/gifs/art468.gif)

[ Arts Index | Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Posters and Posers

A Call to Action: Malaquías Montoya's Vietnam-era poster links domestic resistance to anti-war protests

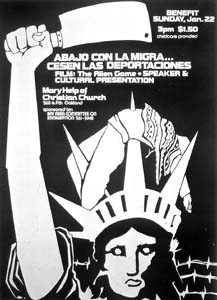

Malaquías Montoya's political posters still engage, while today's artists ask '¿Que Es Chicano?' By Ann Elliott Sherman IN A RARE bit of synchronicity, a retrospective of posters by a man who helped define the term "Chicano artist" appears just two blocks down South First Street in San Jose from another show that poses the question of what it means to be Chicano today. In his resolutely direct graphics, Malaquías Montoya (whose works are now on display at MACLA) knew exactly what he wanted to communicate and how to deliver that message with maximum impact. There's no equivocation, no clever sniping from the safe distance supplied by irony--just a bold statement of what's happening, who's the enemy, who's a comrade in the small and large scheme of things as Montoya sees it, mass-produced on paper. In Resistencia, a wrench-wielding worker in overalls joins a long-haired youth to support the cause literally dawning on the horizon over silhouetted marchers. Against an army-green background, brown fists join yellow to frame profiles of a Vietnamese and a Chicano backed into each other in Vietnam Aztlan, a punchy bilingual call to pull out of Vietnam and win through solidarity. Public-service announcements extraordinaire such as these were routinely plastered on telephone poles, walls and kiosks, their very immediacy and prosaic quality lending them an even greater sense of urgency. Montoya's posters demand attention through the effective interplay of color and composition, with just enough shock value to jolt the clueless out of complacency. Some gringos might not be able to translate the title of Abajo con la Migra, but the arresting image of the Statue of Liberty holding up a cleaver with a campesino impaled on her crown says it all. Montoya's symbolism is often lyrical. A recurrent motif is the sturdily thorny agave or century plant, wrapping itself around a border fence, tearing through a shrouding U.S. flag, sprouting right out of the stars and stripes. It is the artist's homage to the endurance of his people. In posters alerting a domestic audience to parallel movements for self-determination worldwide, Montoya displays a knack for marrying his visual poetry with great quotes from fellow revolutionaries like Ernesto Cardenal and Renny Golden. Not only is it unusual these days to assume such a capacity for thought and feeling among the public, but this perspective emphasizing commonality and empathy feels positively liberating in these insular times. THE LEGACY of artistic service to one's community lives on, but today's Chicano/a artists want to be free to follow the muse wherever it takes them, into galleries as well as the streets. The answers to the query ¿Que Es Chicano?/What Is Chicana? (now at the Collaboratory/San José) suggest that the pride and consciousness fostered by forerunners like Montoya have been internalized. That one's culture will be reflected in the work is a given, but it is just one aspect of the self in need of expression. The raw and vital sculptures of Al Preciado can range from the battle-scarred mutt Pocho Dog to the altar as personal history/manifesto, I'm an Artist Before I Am a Chicano, in which the artist's cast hands gradually fashion, nest and set free the hummingbird, symbol of inspiration. That hummingbird returns in Yolanda Guerra's untitled diptych, sipping at the nectar of the artist's blood--her stigmata--a creature she must cradle even as others of its kind attack her. Clear-cut social commentary is still alive and well. In Emigdio Vasquez's photorealist work, the iguana-skinned homeless man pointedly posed next to a bus bench exhorting Pledge Your Allegiance levels an unflinching bloodshot gaze no viewer can escape. Ricardo Duffy's monotype The New Order takes on the conversion of Atzlan into Marlboro Country. Richard Godinez's Manifest Destiny Part II tackles the same topic in a painting that suggests freeze frames from a documentary. On one side of the diptych, appropriately bathed in red yet partially obscured, a Mexican family prepares to cross the river to the States. Juxtaposed in black-on-gray, hundreds of riders stretch across the desert in the land rush to stake a claim to territory taken from Mexico. The blurred focus carries the sense of both swift movement and a bad dream. Contrasting power dynamics also fuel Carlos Pérez's Dangling the Carrot, in which a tattered burlap dog behind wire fencing pants at the bone offered on a white rococo shelf on a wall of black taffeta. The choice of materials carries all the implications of class distinctions between those who hold out what no one else wants and those who need it to eat. Perhaps Morgan Rosales' exquisite papier-mâché warrior's headdress, Chicano Subconscious Helmet, says it best: The stuff of past glories and inward struggles is willed out, in brave proclamations of identity that are both personal and cultural.

The Art of Protest: The Posters of Malaquías Montoya runs through Aug. 23 at MACLA/San José Center for Latino Arts, 510 S. First St., San Jose (408/998-ARTE). ¿Que es Chicano?/What is Chicana? runs through Aug. 30 at The Collaboratory/San José third-floor gallery, 325 S. First St., San Jose (408/288-2229); poetry evening featuring Las Poetas of the Obsidian Tongue and others, Saturday (Aug. 9) at 7pm. [ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.