![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

Trails and Tribulations

'Metro' writer Jim Rendon goes traipsing through the Bay Area Ridge Trail and finds it's not that far from silicon to solitude. Not if you have something light and cheerful to think about --like your future

By Jim Rendon

MY FIRST THOUGHT is boar. Wild pig. Although the full moon is bright enough to throw a black shadow behind me, I feel like I can't see a damn thing. And eight or 10 somethings have appeared out of nowhere and are leaping, crashing through brittle grass, hauling ass right across my path.

They're boar, I think, because of the poster I glanced at as I left the safety of my campsite at Joseph D. Grant County Park to take this moonlight hike in the eastern foothills of Santa Clara County.

Bold capital letters spelled out a warning, as if the sign were a "Wanted" poster. A line drawing of the suspect told the story--scraggily facial hair, protruding front teeth, squinty eyes (definitely the criminal type)--followed by a description of its deviant behavior--a tendency to lurk around campgrounds, nocturnal food theft--warnings about its size (up to 460 pounds), aggressiveness if cornered and probably something about small children that I skimmed over. But no written word could compete with the artist's impression of those curling oversized incisors.

I freeze and watch as the nocturnal marauders bolt toward the open field to my right. Even with my flashlight, I can't make out much but their size--about the same as young calves. I listen and hear the low moaning of cattle in the distance.

With my light, I scan a group of large unmoving dark shadows that I hadn't noticed before. Since I'm expecting to see hooves and a low, hanging head, it takes me a minute to realize that what I'm looking at is a bit less bovine--a thick trunk and spreading shrub branches.

OK, but those other creatures certainly were not bushes. Or cattle. But do boar travel in packs? Can they actually leap? Don't they make some kind of noise? How is it that I don't know anything about these beasts--something so common they are considered pests just one ridge line away from Silicon Valley?

Gappy Trails to You: Local trail is a work in progress, with hurdles of private ownership, corporate expansions still standing in its path.

The Trail Less Traveled

It seems improbable from the congested lanes of Highway 101, but Silicon Valley can still be an untamed, if not wild, place. In small pockets scattered from Milpitas to Gilroy and from Los Altos to Saratoga, a system of parks and trails harbors remnants of the valley that have survived the dramatic changes and intense development of the last 50 years or more.

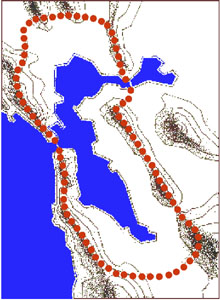

For the last 15 years, the Bay Area Ridge Trail Council has been working to link many of the these pockets into a 440-mile trial that rings the entire bay from Gilroy to Napa (see accompanying story and map).

The trail is currently only about halfway completed. According to interim executive director Bob Power, the process of carving a public pathway through scattered pockets of South Bay parkland--often broken up by long stretches of privately owned property--has been difficult.

So far, Santa Clara County has only dedicated 41 miles out of a proposed 180 miles of trail. Much of the private land, Power says, is developed or scheduled to be soon, like Cisco's proposed facility in the Coyote Valley that sits inconveniently between two existing sections of trail.

The Ridge Trail, Power explains, will be different from many of the large, well-known hiking trails in America. The Appalachian Trail on the East Coast and the Pacific Crest Trail here in the West cover thousands of miles. While many people do shorter multiday trips on these trails or even just head out for a day hike, the trails are also built to be traveled end to end by backpackers and therefore have ample campsites a day's hike from one another.

But here, on this roughly formed foothill-top loop around the bay, there are at present very few places to camp, and none of them are connected by trail. The only way I can find to hike the dedicated portions of the Bay Area Ridge Trail in this county is to engage in a kind of amped-up hiking relay race where I hike out the length of a section of trail, double back and then, after extracting my tired feet from my hiking boots and scarfing down a PB&J, climb in my car and race off down the freeway to the next section of trail.

Nonetheless, I am determined to hike what I can, to discover how the vision of a contiguous nature trail fits into a valley obsessed with economic growth that expands according to Moore's Law, not nature's. And I want to hike because like so many other people in this valley after the crash, I have been thrown by the wayside of that economic expansion. Walking is good for the spirit.

The Eastern Hills

When I drive up Mt. Hamilton Road, I'm amazed at its emptiness. Only a handful of personal palaces dot the landscape as a bloated full moon balances on the horizon. At long last, the overinflated SUV that has been trying to drive up my tailpipe turns off, and as I wind toward Lick Observatory at dusk, Silicon Valley seems surprisingly peaceful.

Joseph D. Grant County Park contains one of two sections of the Ridge Trail in Santa Clara County's eastern hills, and it is the only eastern park that allows camping along the trail.

I pull into a campsite and set up the tent I haven't seen in two years. Just the smell of the musty nylon brings me back to the summer 10 years ago when a college friend and I bicycled cross-country and lived out of this tent for two months. As I stake the tent, set up the stove and begin making dinner, I feel like I've finally arrived home after a long absence.

But by the time I've eaten dinner, cleaned up camp and read for a while, it's all of 8:30pm, and I'm feeling bored. On the heels of a high-tech journalism career, a life in big cities, an itinerary of international travel and long, long hours in front of a computer, I am just not used to having this much uninterrupted time to think.

Though that is in part what I came here for, thinking about my own life, I suddenly recall, can be a particularly unpleasant process. It's why my dishes are washed and stacked, the floor is vacuumed, why I've read more books in the last few months than I have in last few years. Now, left alone with nothing but the space I've been looking for, I am once again listless and uncomfortable--uncomfortable enough to seriously consider going to bed at this ridiculously early hour.

So I stand up and venture away from my campsite into the darkness. Just a few yards at first, then a bit more. Finally, I sit on a hillside and look up at the full moon. Off in the distance, the bullfrogs have begun their evening chanting.

I let my eyes adjust slowly and reacquaint myself with the darkness and just listen for a while. The boredom is gone, and I find myself wondering where amphibians could possibly live in this parched landscape. Below me, I notice a dirt trail heading off toward the croaking frogs, and so I set off down the hill, toward the belch of bullfrogs and into the boar-infested night.

Day Two

It's 9:30 in the morning and already warm as I set off on my first leg of the Ridge Trail. Dutch Flat, despite its name, rises from the campground in a Dr. Seuss-like spiral toward the ridge. At the top, I feel like I'm straddling two separate worlds. In front of me, houses line up like soldiers; to my back, green hills echo the sounds of coyotes and cows and birds and frogs.

On the silicon side of the ridge I can hear a constant hum--as if I'd sneaked into the inner workings of a vast building. It's the sound of machinery turning, air moving, electricity humming, the pumping of the machine heart of Silicon Valley.

Walking south, I lose contact with the valley, but as soon as the visual flotsam of houses, freeways and offices disappears from view, the backlog of junk in my head steps in to take its place. I run through the plots of films that I don't even like; add and subtract books from my reading list; pry under the rock marked "Why am I hiking around Silicon Valley?"; ask some sticky questions about my relationship; and finally begin to ponder a subject both vast and terrifying: what exactly it is I'm doing with my life.

Like so many other people on the silicon side of the ridge, I got sucked into the spinning martini of the new economy, leaving my old media job for a dotcom that burned through $8 million in a matter of months. My next gig was the next new thing--a business magazine covering the wireless Internet.

Things were looking bright enough that the magazine sent me to London to cover the European mobile market. Ten months, hundreds of pints and dozens of expense reports later, I got a Friday-night call from human resources. The mobile Internet, too, had run its course.

And so, on a damp January morning I sipped a last cup of tea and watched two meaty Englishmen pack up my apartment in a matter of hours. I landed back in California with no job, no car, no home, no computer and in greater flux than I had been at any point in my adult life. All the trappings of stability that I found so constraining--and had complained about so bitterly--were suddenly gone.

My employed friends looked at me admiringly and confided that they secretly wished they could trade places and be rid of all the strings tying them to an office, a cubicle, a paycheck. It's the same look I would have given myself six months ago. But now, untethered from stability, I was feeling not so much awe, as downright horror at the gaping hole of my future.

Making a mental note of my horror, I picked up my pace. I cut a line south along the ridge, out of sight of the valley. I get the distinct impression that I am actually heading somewhere, that if I were to stay on this trial, I'd end up somewhere very different from where I am now.

But soon the trail turns back into the valley and widens into a dirt road, looping north again and crossing isolated open fields. I'm so absorbed in the isolated beauty of this place, it takes me a minute to realize that what I'm hearing in the distance is not a plane engine but the clatter and bang of a generator. Tracking the sound, I walk around a bend to see a figure in a white hazmat jumpsuit, safety goggles and green gloves methodically spraying some sort of algae-hued liquid into the brush.

After enough of my gawking, he stops his spraying and comes after me. Peering at me through clear plastic safety goggles is Dan Clark, a native-plant restoration technician with the county's parks department. He has been spraying Garlon 4, an herbicide designed to eradicate the weed black mustard.

Removing his goggles and wiping his sunburned forehead, Clark explains that both black mustard and star thistle, plants that arrived here with other grass seed from overseas, are taking over much of the eastern hills. Both weeds can grow as high as 8 feet and take up water and sun that grass needs in this hot dry landscape.

Clark is fighting back on this patch of nowhere with a combination of disking, spraying, controlled burning and fencing to keep out the wild boar that root up and spread the weed's seed. The county is also testing the release of weevils, insects that eat the star thistle seed.

In the weed's place, he's replanting native grasses like creeping wild rye and blue wild rye. Clark's multifront assault is a modern attempt at making nature, for the lack of a better word, more natural. Agriculture has so changed the land that leaving it alone would be a disaster, Clark says. Today, even nature needs tending from a guy in a hazmat suit.

The Valley Floor

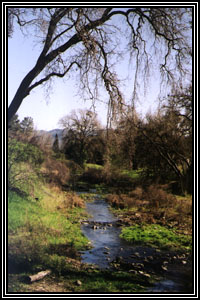

After such quiet meandering in the foothills, driving seems like a manic task that no I longer feel suited to perform. But it's the only way to get from here to the top of Coyote Hellyer Park. After negotiating lane changes on 101, dodging schoolchildren on side streets and wedging into a parking space, I start off down the trail, which winds along Coyote Creek and passes under the freeway.

As I approach one of the underpasses, the knock and ding sound of trucks and cars is overwhelming but oddly musical, and I can't help but pause to check out the graffiti-scrawled underpass and listen the rhythm of the traffic above.

The Coyote Creek was one of the first pathways through the valley. The Ohlone Indians used the passage to move north and south. Spanish explorers did the same. Monterey Road follows the creek for much of its length, as do Route 101 and now the creek trail.

For hundreds of years, all around this riparian corridor, people have overlaid the landscape with their own vision. Though it's infringed upon, the creek still moves along its age-old path from the Diablo Range to the bay. Walking along it, slipping under route 101, I was sure that something fundamental about the landscape remains.

But at the same time, I feel out of place here. The path is broad and paved--more a freeway for exercise than a hiking trail. No matter how fast I walk, I never feel that I'm moving quickly enough. Joggers and cyclists pass me by, taking a moment, I think, to stare at my greasy hair spiked in all the wrong directions. After living outside, even for these few days, I am something from the woods that is suddenly out of place wandering the fitness paths of the suburbs.

Hiking here, along the Coyote, reminds me of being a kid, because kids inhabit a world built for others, where roads are for cars, not bikes, and sidewalks are for walking, not skateboarding. Everything kids do becomes an act of act of subversion. And that is what this trail is.

Hiking trails belong in the woods. But in too many places, there are simply no woods to be found. In too many places, you must simply hike right through someone's tidied neighborhood, fouling it with your camping stench, hiking boots and scratchy beard, drawing strange looks from behind slatted blinds.

That night, lying in my sleeping bag under the dense canopy of young redwoods at Mt. Madonna County Park, sleep won't come. I stare at the arc of the tent roof, listening to the nocturnal chatter drifting over from the blue tarp Ewok village a few campsites away. I can't help but think about the nights I've spent on a friend's couch staring at his ceiling, ticking off the list of things that I need to accomplish: find a place to live, drum up work, write more, stick to a schedule. In short, begin the long trudge toward order and stability in my life.

And every day I watch myself wake up, make halfhearted attempts at the most pressing things on the list, avoid the rest, pursue no single thing with focus. It's as if deciding on an order, opening one door irrevocably closes another.

As soon as the layoff came, I knew that this break between jobs would be an important one. I am acutely aware that it is rare to have this kind of an open-ended untethered break in your early 30s when most people are getting married, having children, buying a home.

The problem is that when I sit down to look at my life and the things in it that I'd like to tinker with, the list becomes long, varied, filled with items that appear to be mutually exclusive, all of which are important, all of which I have equal desire for, any one of which I may not have the talent, smarts or drive to accomplish. The collective weight of all this leaves me paralyzed, hoping, like a cornered mouse, that if I just don't move, maybe that frothing beast with the fangs will lose interest and go away.

Day Three

In the morning, I pack up my gear under the spindly redwoods, climb in my car and begin winding down from the dense forest back into the valley. Almost immediately, my cell phone starts ringing with messages, and my CD player refuses to accept my selections. It takes me a few minutes of fighting with my technology to just turn off the phone, set the CDs on the seat and finally drive north in silence back along the Coyote toward Santa Theresa County Park.

Santa Theresa, draped over the shoulder of Coyote Peak, marks a boundary between developed San Jose to the north and the rural Coyote Valley to the south. Every view toward the bay is tinged with orange smog, dominated by the cluster of high-rises downtown. And every view looking over the backside is empty, green and dotted with tree-tufted hills.

The trail through the park is steep, winding through upturned scattered boulders cast by some long-ago volcanic eruption, passing through tiny isolated valleys where nothing but the green rim of open fields can be seen on all sides. Finally, the trail switchbacks down a steep hillside and follows Calero Creek as it wanders alongside a leafless orchard carpeted in golden flowers.

This is the kind of trail that I imagined I'd find, a narrow rocky path dropping out of the hills onto flat agricultural land. And I feel like I'm seeing the valley the way it was decades before it was a twinkle in the eye of early tech pioneers at IBM, Fairchild and Lockheed.

From here, I can see so many of the visions that have been laid over this landscape: grazing in the hills, orchards on the flats, IBM's research center cantilevered over the steep hillside, personal palaces tacked to the hill's base, and the park and this trail cutting through it all, trying to create a place for all humans to connect again with the earth, to untangle their inner dilemmas, to move through the landscape and their own minds step by step.

Looking around at Silicon Valley, and even looking at myself, I can't help but put some credence in the old cliché of constant reinvention. In the context of technology, that cliché is meant to conjure up visions of renewable wealth and boundless economic growth. But when it is laid over a landscape tiring of a century of makeovers, it is perhaps less morally triumphant.

When reinvention comes to roost in your life, however, each choice takes on a greater gravity. Perched at the point of departure, I see myself looking at the beginning of new paths, trying desperately to understand how they will look in hindsight. Hopeless. The thing with reinvention, be it personal, economic or environmental, is that it requires a dangerously steadfast focus on the future, an ability to pretend that tragedy is something that befalls others.

Day Four

Since Sanborn Park doesn't allow camping in the spring, I am forced to bed down for the night at Saratoga Springs. The temperature has fallen, and under the umbrella of redwoods, no moonlight peeks through. If Dickens had set Oliver Twist in a campground, I would not need to describe the private campground at Saratoga Springs.

The tent campsites are little more than double-wide parking spaces in a muddy, tire-rutted swath that parallels the creek. Every other campsite has a half-broken picnic table. On the opposite side of the creek and 20 feet above me is a parking lot full of RVs that, over time, have grown haphazard appendages of tents and tarps.

I paid an extra $5 for shower privileges only to discover that the shower room is no larger than a pantry and that the mold between the tiles grows in fuzzy clumps. And, of course, the door won't lock.

I opt to shower in my socks. As I'm lathering up, I have to reach over every 20 seconds to push the button that keeps the hot water flowing, hoping that I can avoid rubbing against the tendrils of mold reaching out for my hand.

Soaped up and eyes closed, I am about as helpless as a person can be. And in that state of near fetal helplessness, I have this vision: someone suddenly opens the unlockable door, expecting to shower, and instead finds me, lathered up, blind and naked except for a pair of black socks. I just can't stop laughing.

I get an early start in the morning and drive up to Skyline and head south, looking for the trail head. As I start out on the trail, a young doe bounds up a hillside and then stops. She twists her head around, gives me a long look, then simply returns to grazing.

The trail meanders along Highway 35, bumping into the road in a few places. Nonetheless, this place is beautiful the way that Northern California is supposed to be. Towering redwoods and Douglas firs frame tiny pinches of blue sky. The leafy green undergrowth reflects stray beams of light. While I have often driven far to backpack for days in the lush coastal forests, I can't help but think how undemanding this landscape is.

After three days of hiking, I have developed a blister on my big toe, and my small toe is bruised and sore. My legs ache, and if I sit for more than 10 minutes, everything seizes up. After several hours, I feel that I should have been at Saratoga Gap long ago--the point where Route 9 meets 35, where my hike will end. But as I anticipate the junction around each bend, I am disappointed. I consider turning back, thinking I may have missed a turn or misunderstood the distance. But I move on a little farther, pushing sore muscles, until finally, I see it. The end of my journey.

A parking lot.

It's fitting that I should hike 7 miles to be in a parking lot that I drove past just three hours before. After all, this is Silicon Valley. From this spot, you'd expect a scenic view, but the view of the valley, so spectacular from graffiti-covered Summit Rock, is obscured by trees here.

A couple pulls into the overlook in a new convertible Volvo. I ask them the time, and we talk for a few minutes. They are friendly, and suddenly it occurs to me that they might offer me a ride back to my car several miles down the road. But without saying a word, they walk past me, climb into their new convertible, lock the doors and pull out.

Only then do I get a mental picture of how they must have seen me. My boots are off to air out my feet. I've got a compressed PB&J in my hands. My hair is sticking straight up, and I haven't shaved in four days. They probably felt lucky to escape with their soft top and their lives intact.

So I stuff my feet into my boots, shoulder my bag and get going again. This time, I'm moving faster, trying to make time and nothing else. The scenery the second time through is much less interesting, so there is little to look at. I keep moving my legs till they go numb and my blistered bruised toes cry out for mercy. And finally, in this overextended state, it happens.

My head begins to empty, to spin out the last of the movie plots and book lists, and I finally let myself take a bit of a look at that gaping empty hole of my future, at all the choices waiting to be taken up.

And once I look good and hard, it doesn't seem any less horrible, but perhaps more human in scale. After more than a month of near paralysis, I can see that indecision is also a choice, and a terrible one.

From the deep recesses of things I learned in college, wisdom from some 19th-century German philosopher resurfaces. Decision-making, he argued, was ultimately an irrational process. You could spend a lifetime adding up the pros and cons of a situation and still be no closer to a good decision than when you began.

Ultimately, every decision, every step forward in life is simply a leap of faith, a jump into the black unknown. Much as we like to think that we can manage risk, whether in business, in our lives or in the environment, we are, every day, really just closing our eyes and falling forward.

That uncertainty, that empty horror, is the necessary starting point for anything new. And faced with it, you really have no choice but to simply keep moving, walking forward toward a new bend in the trail.

And with that realization, I walk up a rise and into the afternoon light. My screaming feet and quivering legs and wandering mind all fall away from me, and I just marvel, walking fast through the trees, surrounded by all of this life.

[ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.

![]()

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

The Trail Less Traveled: The Bay Area Ridge Trail, which will ultimately cover 440 miles, is now about halfway complete. Organizers hope to see it finished by 2010.

The Trail Less Traveled: The Bay Area Ridge Trail, which will ultimately cover 440 miles, is now about halfway complete. Organizers hope to see it finished by 2010.

Send a letter to the editor about this story

.

From the August 8-14, 2002 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.