![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

The Secret Garden

How Palo Alto created a park all its own--and you can't go there--nyah! nyah! nyah!

By Loren Stein

A QUICK 10-MINUTE drive from the heart of Palo Alto up the gently sloping hills of Page Mill Road, nature lovers will discover Foothills Park--1,400 sprawling acres of woodland oak forests, mixed evergreens, rugged chaparral, shaded streams and rolling grasslands.

Two enormous slate-flat meadows stretch out through the center of the park, perfect for picnics, frolicking or soaking in the sun. An 8-acre boating and fishing lake, Boronda Lake, is carefully stocked with red-eared sunfish, largemouth bass and channel catfish.

The park offers 15 miles of hiking trails in all directions (though mostly uphill), sweeping views of the bay, picnic tables and camping facilities, a nature center (and nature programs), and the chance to glimpse bobcats, gray foxes, Columbian black-tailed deer, coyotes--and winging high above, red-tailed hawks and great horned owls.

"It's a wonderful escape from the hustle and bustle of downtown Palo Alto, but it's so close, only 10 miles away from most of the city," observes Lester Hodgins, supervising ranger for Palo Alto Open Space. "Yet it seems, for most people, like the wilderness."

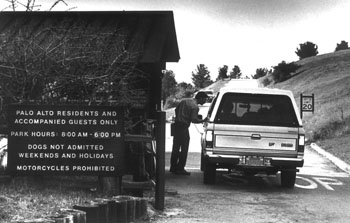

There's one tiny catch, however: most Bay Area denizens can't go there. Although there is no entrance fee, only card-carrying, bona fide residents of Palo Alto (which means "Big Stick" in Spanish) will be waved in by the uniformed rangers who guard the front gate. Guests are allowed in only if they are accompanied by city-dwellers.

One of the park's most attractive features, to Palo Altans at least, is the resulting scarcity of human visitors. On a recent sunny morning, the park was quiet and serene. The lake glistened as ducks glided over the water. The trails seemed empty of people. The only Homo sapiens in sight were two groups of young children playing in the open grassy meadows. (The park is open from 8am to sunset.)

No other park in the Bay Area restricts its use to residents of a particular area, but living next to Stanford University, Palo Altans have grown accustomed to the local practice of privatizing facilities paid for with public funds. Currently, about 120,000 people visit Foothills Park each year, and since its opening in 1965 the city has never experimented with having nonresidents (who are not guests) allowed in.

"It's of course difficult, as folks come to a park to have a good time, and we want to make sure that everyone who comes to the gate has a good day," says Gregg Betts, superintendent of Palo Alto's Open Space and Sciences. Those who are refused entrance to Foothills Park are offered nearby alternatives, such as Arastradero Preserve and Los Trancos Open Space Preserve, he says.

Immoral, Illegal and Elitist

Regardless, the Palo Altans-only policy of Foothills Park has sparked bitter controversy over the years, as has the park itself. Back in 1959, Dr. Russel Lee, the founder of the Palo Alto Clinic (now the Palo Alto Medical Foundation), offered to sell Palo Alto 1,200 acres he owned in the foothills if the property would be used as a park and remain undeveloped.

He offered the land at a price far below market value. The City Council eagerly agreed and in 1958 approved a contract to buy the land for $1,294,000. The city made an immediate payment for 600 acres, promising to buy the remaining land within six years, and a spending measure was placed on the ballot.

Then the trouble started. A citizens' group opposed the purchase, calling for a referendum on the issue and claiming that the park's purchase had been shoved through the political machinery without enough input from Palo Altans. Then another citizens' group filed a taxpayers' suit in Santa Clara County Superior Court on similar grounds, charging that the council's ulterior motive was to use the proposed park land for real estate and subdivision development.

Apparently, behind all the tumult lay growing fears that the land, adjacent to Los Altos Hills and several miles from most of Palo Alto, would be used primarily by wealthy Los Altans (whose town fathers had expressed no interest whatsoever in paying anything for the property) although purchased and operated on Palo Alto tax dollars.

Actually, Palo Alto had asked the neighboring cities of Portola Valley, Los Altos Hills and Los Altos to help buy the land for the park and offered to create a regional nature preserve. When the other cities declined, Palo Alto residents ended up footing the bill to acquire the property. The embattled council, to save the project, pledged that the park would exclude non-Palo Altans, a policy that has been enforced with rigor for 37 years (and has ended up, in the salaries of guards, costing more than the purchase price of the park).

In 1991, then-City Councilmember Ron Anderson led an unsuccessful crusade to open Foothills Park to nonresidents. He argued that most of Palo Alto's tax dollars come from commuters who work in the city but live in other communities, and that residents have been more than compensated for their original investment in the property.

Two years ago, Anderson (who had moved out of the region) threatened to sue the city to open the park to non-Palo Altans, calling it an "immoral, illegal and elitist" policy. According to supervising ranger Lester Hodgins, the ACLU also threatened to sue over the restrictive policy, but never did.

The Foothills Park exclusion policy has never been specifically tested in court, say both Superintendent Betts and Palo Alto Senior Assistant City Attorney Wynne Furth. Still, California courts have upheld such restrictions before, says Furth, and points to a park in Southern California where nonresidents are likewise barred from entering, among others. When disagreement over the park erupted again in 1991, City Attorney Ariel Calonne reassured the City Council that the policy was legal based on a number of legal precedents. However, exclusion of nonresidents from a city-owned park on environmental grounds has never been specifically addressed by the California courts.

Park administrators say they worry that opening Foothills Park to the general public (Palo Alto's population is 59,000) would lead to overuse and a degradation of its pristine natural setting. "The ecology here is much more fragile," says Betts, explaining that the park's habitat includes wooded areas, a greater number of deer and wildlife as well as rare and endangered plants and wildflowers. No bicycles or horses are allowed on the trails, he adds.

City officials also fret about a spike in crime if outsiders are allowed to run roughshod over its hills and valleys. (Palo Alto's other 30 parks and nature preserves, however, are open to nonresidents.)

Protecting the park from strangers is more than a little ironic, given the fact that the land was confiscated from its original inhabitants, the Ohlone Indians, by Spanish explorers in the 18th century. For history buffs, Foothills Park was part of Rancho del Corte de Madera, and later the Doughertys farmed there for 40 years, until 1910, on land leased from the Boronda family. The Borondas sold the land to a San Francisco broker, Sanford Sacs, who then sold it in 1941 to Dr. Lee.

[ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.

![]()

Private Parts: Foothills Park is for Palo Altans only, and driver's licenses are routinely checked for entrance.

Send a letter to the editor about this story

.

From the August 8-14, 2002 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.