![[Metroactive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

![[Metroactive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

The Thinking Heart

Etty Hillesum's remarkable Holocaust writings are often lost in the shadow of Anne Frank's famous diary By Tai Moses

IN HER LUMINOUS foreword to An Interrupted Life and Letters from Westerbork, Eva Hoffman writes that "all the writings [Etty Hillesum] left behind were composed in the shadow of the Holocaust, but they resist being read primarily in its dark light." This is a significant statement, for, unlike authors of many Holocaust memoirs or diaries that leave a reader nearly paralyzed with depictions of Nazi horrors, Etty Hillesum left an incomparable record of the meaning of life that embraces both horror and beauty. Hillesum was a Dutch Jew who lived in Amsterdam and died in Auschwitz in 1943, at the age of 29. She began a diary nine months after Hitler invaded the Netherlands and continued her narrative for two years. Also included in this volume are letters Etty wrote to family and friends from Westerbork, a detention camp in the north of Holland where Jews were held before transport to the death camps of Poland. Hillesum went voluntarily to Westerbork in July of 1942, at about the same time a young girl named Anne Frank began writing her diary in the attic of a house a few miles away from Hillesum's home in Amsterdam. After the war, a writer friend of Hillesum's tried to get Etty's diaries published but met with no success. The diaries languished unread for 38 years until, in 1980, the eight handwritten notebooks were shown to J.G. Gaarlandt, a Dutch publisher who was entranced upon reading the first sentences. First published in the U.S. in 1982, An Interrupted Life is taught in university courses on Holocaust literature and has garnered a small but passionate following, but for the general public, the book is often overshadowed by The Diary of Anne Frank, the familiar touchstone by which most of us measure Holocaust diaries. This edition marks the first time that Hillesum's diary and the letters from Westerbork have been published together in English. The ensuing portrait is a transcendent work, created during one of the darkest eras in modern history. HILLESUM, WHO aspired to be a writer, was so attuned to currents both within and without that she often suffered from overwhelmed senses; she describes feeling like a "soul without a skin." It is this receptivity that makes her observations so original and compelling. This territory, of Holocaust documentary, has been visited before but never with a view as capacious as the one from Hillesum's soul. What makes her story so unusual is that Hillesum's passion, even in the lengthening shadows of Hitler's genocide, was for self-scrutiny. She possessed a lucid, unfettered mind, capable of imaginative leaps of intellect. Her diary is a chronicle of an intellectual and spiritual development that in normal times might take a leisurely lifetime but out of necessity was fitted into the brief interstice of two years. The first page of her diary contains the sentence "I am accomplished in bed." The last entry, roughly two years later, reads simply, "We should be willing to act as a balm for all wounds." Between these two statements, the first boastful, the last wise, lies a profound internal transformation in which the volatile, self-absorbed girl leaves behind her Bohemian sensibilities and evolves into the compassionate, profoundly ethical individual one meets later in the Westerbork letters. In the diary's first half, Hillesum reveals herself as ardent and impulsive, given to idealistic whimsy but capable of flashes of pure brilliance. Central to her life during the diary years was the intense relationship she had with Julius Spier, a psychotherapist who had studied with Carl Jung and founded an analytic process called "psychochirology," the reading of palm prints. He also engaged in an unorthodox method of therapy that began with a wrestling match between doctor and patient. To tame the mind, he believed that one must first conquer the impulses of the body. Today, his methods would raise a few eyebrows, but Spier seems to have been an undeniably charismatic and intuitive man, and Hillesum, who was always one to struggle for self-mastery, was intrigued by him. Spier became Etty's friend, spiritual mentor and ultimately her lover. She suffered storms of conflict over her feelings for him. She was captivated by the "confounded eroticism" both possessed, yet she yearned for a completely spiritual union free of physical longing. The relationship was certainly the most influential of her life, for it was through Spier's encouragement that she began to reach into the depths of her being and begin the interior conversation that became a dialogue with God. MIDWAY THROUGH the diary--about the time Jews are ordered to wear the yellow star--one detects a maturing in Hillesum's thought. As the Nazis instituted one after another of the repressive edicts that made the lives of the Dutch Jews miserable, Etty increasingly drew sustenance from her spiritual beliefs. She describes a newfound serenity: "Somewhere there is something inside me that will never desert me again." Yet she never withdrew into the contemplative life; she remained always engaged with the world and with her wide circle of friends. Her spirituality was rooted in her observations of a world in which suffering and delight were intrinsically bound together. Hillesum's religiosity was highly personal, almost Whitmanesque in its ecstatic rhythms. In her writings is also something of the fierce visionary spirit of Simon Weil. Her own description of her experience seems to place her squarely in the company of mystics: "When I pray, I hold a silly, naive, or deadly serious dialogue with what is deepest inside me, which for the sake of convenience I call God." One of the most striking elements of Hillesum's legacy is her compassion. She refused to join her fellow Dutch in despising the Germans. Etty was no innocent, she was simply loath to add another iota of hatred to a world already reeling with abominations. She kept trying to find, even in the Nazis, some grain of humanity; yet she was careful to note that "the absence of hatred in no way implies the absence of moral indignation." Hillesum wanted to be the "thinking heart of the barracks." Her eloquence and candor, her expressive, questioning mind, are all wondrously present in her diaries and letters. Perhaps most remarkable is that in the midst of a campaign bent on extinguishing her and her people, Etty Hillesum created a work of profound connection. She was wildly in love with every moment of her life, and although she never knew it, she succeeded in at least part of her most earnest desire: "And if at the end of a long life I am able to give some form to the chaos inside me, I may well have fulfilled my own small purpose."

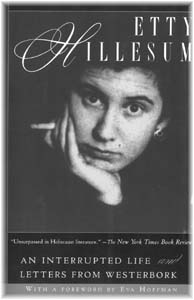

An Interrupted Life and Letters From Westerbork by Etty Hillesum; Henry Holt & Co.; 375 pages; $15.95 paper. [ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.