![[Metroactive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

![[Metroactive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Beyond Bond

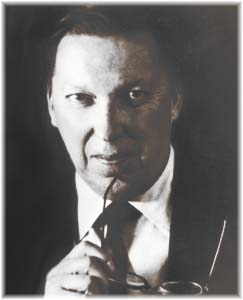

Man of Intrigue: Spy novelist Charles McCarry

Forget Fleming; lose Le Carré--Charles McCarry is the undiscovered master of the spy novel By Morton Marcus THE BRITISH ARE generally considered the nonpareils in foreign-intrigue literature. Although they didn't invent the genre, they perfected it, and are credited with the first spy novel that can be considered serious literature, Erskine Childers' still enthralling 1903 classic, The Riddle of the Sands. The U.S. has had its share of practitioners in the genre, starting with James Fenimore Cooper's The Spy (1821), generally considered the first spy novel, but none has boasted the depth of vision and literary ability to rank with the Brits. Or so it seems. "Seems," maybe, but it is not the case, as the great Eric Ambler himself proclaimed when he read The Miernik Dossier, the first spy novel by American Charles McCarry, saying that it was "the most enthralling and intelligent novel I have read in years." Such journalists and novelists as Richard Condon, John Gardner, Tom Wicker, George V. Higgins and Christopher Buckley have praised McCarry's novels with equally glowing remarks, while Peter Lewis, writing in Britain's The Daily Mail, said that McCarry "ranks up there with [John] Le Carré in a select class of two." Mysteriously, despite this praise, McCarry's work has not achieved popular success, and at this writing, all of his novels except his most recent one, Shelley's Heart (1995), are shamefully out of print. After writing for Stars and Stripes during World War II and working as a small-town newspaperman, McCarry was a CIA agent in the 1950s in Europe, Asia and Africa and then a speech writer for the Eisenhower administration. He has lived in Washington, D.C., for the past 25 years, rubbing tweed elbows with the powerful and the not so powerful. Although he has written a biography of Ralph Nader, Citizen Nader, and several other nonfiction books, McCarry's reputation among fellow spy writers and foreign-intrigue aficionados rests on six novels. Four of McCarry's spy stories elliptically trace the career of one Paul Christopher, CIA agent and poet. The books' moral and ethical considerations delineate the effects of "professional duplicity" on the human psyche. Understand that McCarry is not concerned with the tongue-in-cheek derrings-do of superheroes on the order of James Bond but with realistic character studies of complex human beings under stress. Add to this story lines, a historian's concern for the 20th century and an elegant prose style that renders time and place with a sensuous atmosphere enriched by years of travel, and you've got all aspects of the master novelist. Note that I did not say "spy novelist." McCarry is writing more than genre literature. He is writing literature with a capital "L." THE FIRST Paul Christopher novel, The Miernik Dossier (1971), may be the most unusual and literary of the lot. It is composed of 89 documents, collected from intelligence agencies around the world, concerning one Taddeus Miernik, a Pole working for the U.N. in Switzerland. Either Miernik is a harmless nerd who suffers from terrible body odor--or he is a master spy. Each document records a different aspect of the subject, as well as comments on other agents who also contribute reports to the dossier. It is soon apparent that the reports reveal more about the writers' shortcomings, prejudices and unfounded suppositions than they do about Miernik. This supposed comedy of spy manners is serious stuff, however, and soon the tragic implications of such human frailties are made all too clear. The method of the novel, of course, is pure Faulkner, and it is worked with the same expertise, although the material being explored does not occur in the backwaters of Mississippi but in the world of international politics. If Christopher emerges as a major character only in the last part of The Miernik Dossier, he is the sole protagonist in the next three novels. In The Tears of Autumn (1974), McCarry's lone bestseller, Christopher travels around the globe in an attempt to unearth a shadowy conspiracy of increasingly terrifying dimensions, which turns out to be the assassination of John F. Kennedy--and the theory presented in the book is not only credible but fascinating to consider. In the third novel of the series, The Secret Lovers (1977), Christopher falls in love with and marries the beautiful Cathy. Set in Rome, the novel revolves around a highly explosive manuscript that has been smuggled out of the Soviet Union, a manuscript that Christopher knows the CIA will want published. Publication, however, will put the writer's life in danger, an eventuality that Christopher has pledged to prevent. Ostensibly a love story, The Secret Lovers examines how the pressures and allegiances of intelligence work affect the lives of everyone with whom the spy comes into contact. Magnificent and chilling, the book, like the others, looks unflinchingly at what we do to each other in the name of job and country. In the end, it is clear that the novel's seemingly innocent title can be read at least two ways, both of them ironically suggestive. Are the characters secretly in love--or are they really lovers of secrets? The final installment in the Christopher series, The Last Supper (1983)--which Richard Condon claims is "like no other spy novel ever written"--unites all the characters of the previous novels and all the subjects referred to in them, to give not only a complete biography of Christopher but also a history of the American intelligence community. It is a tour de force and a fitting end to the Paul Christopher saga. McCARRY'S TWO OTHER intrigue novels are really political thrillers, The Better Angels (1979) and the recent Shelley's Heart (1995). Both center on intrigues at the top level of government, namely the presidency, and both contain the same cast of characters, several of whom are holdovers from the Christopher books. All six McCarry novels create a fictive world as convincing and inclusive as Faulkner's microcosmic Yoknapatawpha County. This is because McCarry is more than a spy novelist. His concerns are similar to Faulkner's, and his characterization and style alone place him beyond the claustrophobic categorizing of genre literature. McCarry is beyond Le Carré in vision and purpose and is producing some of the best, most readable and provocative literature today. In a word, he has set himself the task of recording the hopes, dreams, frailties and mistakes of several generations of Americans whose decisions have determined the course of 20th-century history. McCarry's six intrigue novels can be ferreted out in secondhand bookstores and are worth the search.

Shelley's Heart by Charles McCarry; Ivy Books; 624 pages; $6.99 paperback.

Morton Marcus is the author of the novel The Brezhnev Memo; his new book, When People Could Fly, will be released this fall. [ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.