![[Metroactive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

![[Metroactive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Joyce on a Mission

Samuel Ornitz--novelist and blacklisted screenwriter--was an unsung pioneer of stream of consciousness By Harvey Pekar

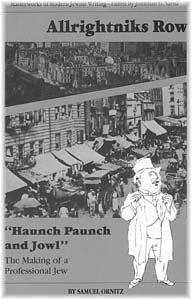

IF ANYONE remembers Samuel Ornitz at all today, it's as a screenwriter who was one of the Hollywood 10; his reputation as a novelist didn't survive the 1920s. Despite the neglect, Ornitz is a significant literary figure whose work deserves to be kept in print and read by anyone who cares about the evolution of the American novel. Born in 1890, Ornitz is a link between Yiddish-speaking, foreign-born American novelists such as Anzia Yezierska and Abraham Cahan, who were mainstream stylists, and the daring Jewish fiction writers of the 1930s: Daniel Fuchs, Nathanael West and Henry Roth. Ornitz belonged to a forgotten avant-garde movement that employed stream-of-consciousness techniques before the 1922 publication of James Joyce's Ulysses brought the method to general attention. In 1887, Edouard Dujardin published an entire stream-of-consciousness novel, Les Lauriers sont coupés. Other writers who were using stream-of-consciousness passages prior to the 1920s were George Moore, Arthur Schnitzler, Romain Rolland, Dorothy Richardson, May Sinclair and André Bely. In the U.S., James Oppenheim employed a bit of stream-of-consciousness in his 1914 story cycle Pay Envelope, which anticipated Sherwood Anderson's Winesburg, Ohio. Waldo Frank used the technique in his first novel, The Unwelcome Man, published in 1917. Probably under Frank's influence, Evelyn and Cyril Kay Scott, Harlem Renaissance novelist Jean Toomer, Elliot Paul and Ornitz incorporated stream of consciousness into their writings by the mid-1920s. The pre-Joycean stream-of-consciousness style, influenced by impressionistic French symbolist poetry, was often spare, peppered with ellipses and relatively easy to follow, as in this excerpt from Ornitz's 1923 Haunch, Paunch and Jowl (sometimes titled Allrightnik's Row):

I ONCE TOLD Leslie Fiedler, one of the leading mavens of American-Jewish literature, that Ornitz was an early experimenter with stream-of-consciousness passages. After I'd pointed them out, Fiedler agreed, but he was astounded that he'd missed the fact that Ornitz was such an advanced stylist. He had always associated stream-of-consciousness writing with Joyce's complex prose and the art-for-art's-sake attitude of most modernists. Ornitz, on the other hand, was a didactic leftist who dealt with problems of the poor and political corruption and inequality. Fiedler had grouped Ornitz with turn-of-the-century realists and naturalists like Upton Sinclair, who hoped to bring about political and social change with their work. Indeed, Ornitz was influenced by men like Sinclair and Emile Zola, but that didn't prevent him from using advanced prose techniques. Haunch, Paunch and Jowl, originally billed as the anonymous autobiography of a corrupt Jewish judge, sold fairly well, and is the only Ornitz work still in print, albeit from a small press devoted to Jewish literature. In Haunch, Paunch and Jowl, Ornitz writes vividly about life in New York's Lower East Side around 1910, discussing crime, politics, religious and educational institutions and the labor movement. The novel anticipates Michael Gold's more celebrated Jews Without Money by several years. In his second novel, A Yankee Passional (1927), Ornitz deals with Catholic-Protestant antagonisms. The protagonist, Daniel Matthews, is a deeply spiritual Catholic who builds a religious movement that gains considerable support but runs afoul of the Vatican--as well as of militant Protestants because he is a pacifist opposed to U.S. entry into WWI. Eventually, he's murdered by members of a Ku Klux Klanlike organization, the American Guardians. By the time of A Yankee Passional, Ornitz had absorbed the influence of Joyce. His work became more complex and, at times, pretentious. Like Joyce he employed neologisms, e.g. "sordidsimple," "greengray," "softsmooth." There are also striking parallels between the novel and Nathanael West's 1934 A Cool Million. The heroes of both are naive, saintly, taken advantage of by self-seekers and ultimately martyred, and both books contain fascistic organizations (the National Revolutionary Guard in A Cool Million). These similarities could be coincidental, especially in view of the fact that A Cool Million is a farce and A Yankee Passional very serious in tone, but West did know Ornitz when both were screenwriters. During the 1930s and much of the '40s, Ornitz worked in Hollywood writing scripts for mostly insignificant movies. Primarily involved in political organizing, Ornitz became an official of the Screenwriter's Guild and worked for many leftist causes. Together with other writers, including Theodore Dreiser and John Dos Passos, he visited Harlan County, Ky., in 1934 on behalf of striking coal miners, and the experience prompted him to write a play, In New Kentucky. Like many American Socialists and Communists, Ornitz sincerely believed that under Stalin the Communist Party was a force for good. He stood up for his beliefs, was convicted of contempt of Congress in 1947 and served a jail term. When he found out the truth about Stalin, he was reportedly furious. In 1951, Ornitz's final novel, Bride of the Sabbath, was published. Unfortunately, it's conventional stylistically and deals with the same themes as his earlier novels. Though his work was marred by melodrama at times, Ornitz was a passionate, challenging author. He--along with Waldo Frank, Jean Toomer, the Scotts, James Oppenheim and Elliot Paul--should be cited in accounts of 20th-century fiction. Their exclusion to date has been a serious oversight.

Allrightniks Row: "Haunch, Paunch, and Jowl": The Making of a Professional Jew by Samuel Ornitz; Masterworks of Modern Jewish Writing Series, Markus Wiener Publishers; $9.95 paperback. [ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.