![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

God's Gay Warrior

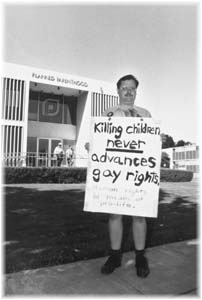

Right to Gay Lifer: In his quest to protect the gay gene pool, activist Steve Cook has made strange bedfellows of the anti-abortionist religious right. Photo by Christopher Gardner

The specter of genetic genocide against homosexuals has led one man to launch a crusade against abortion By Michael Learmonth STEVE COOK is a black sheep, a true eccentric. Not because he's vehemently anti-abortion and devoutly religious, and not because he's bisexual, but because he manages to be both of these at once. "I'm out of the closet as both gay and pro-life," Cook says. He wears a button with the image of a fetus inside a pink triangle, which says, "Human rights start when human life begins." Cook's on a crusade to end abortion, but not for the same reasons as the Christian Coalition or the Concerned Women of America. Like those two groups, he believes abortion under any circumstance is murder. But he has an additional concern. Cook believes some people may soon use abortion to kill off homosexuals before they are even born. After hearing of research that will soon allow scientists to identify genes that influence sexuality, Cook began to fear that that information would be used to selectively abort gay fetuses. He carries with him a briefcase packed with copies of newspaper articles, most from 1993, when researchers first reported discoveries that pointed toward the existence of the so-called gay gene. But Cook's anti-abortion stance and religious convictions pre-date recent advances in genetics by at least 30 years. Cook, who is 41, remembers vividly the day he became a Christian. It was a Sunday morning and he was 7 years old. He was listening to a radio evangelist in his house in Orange County, Calif., and it had quite an effect on him. "I gave my life to Christ in response to that radio message," he recalls. He walked into his parents' bedroom to inform them of his decision. His father was still asleep. He told his mother, and at age 13 convinced her to take him to services at the United Methodist Church. Neither of his parents was religious, nor had they been baptized. But growing up, Cook felt another calling that was more difficult for him to understand. He says that as a child, he liked to play with Barbie dolls, and remembers now that Ken didn't seem to think Barbie was all that in her summer bikini. In Cook's imagination, Ken always wanted to steal away with Alan. "I used to have them kiss each other on the lips," Cook says. Beyond playacting with Barbie's boyfriends, Cook didn't act on his urges. "I buried my sexual orientation and feelings for men as a teenager," Cook says. "Around 1980 they resurfaced." Soon after arriving in San Jose in that year, he began to search for a church that would accept his sexual identity. He found a local Episcopal church that recognizes gay and lesbian people as church members, and he was confirmed in 1981. Born to Be Gay COOK SAYS he became a member of National Right to Life in the late 1970s. In the years since, he has memorized an arsenal of sound-bites to convince anyone wavering on the issue or to shame those who believe in a woman's right to choose an abortion. "A child has brain waves at six weeks and a beating heart within 24 days," he says. "Most women don't know they're pregnant for three weeks, so every abortion kills a beating human heart." Today, Steve Cook is a part-time pro-life activist, a substitute teacher for the Alum Rock School District and an active member of St. Edwards Episcopal on Union Avenue, which affirms its gay membership but takes no position on abortion. In 1993, two scientific discoveries--and the ensuing media orgy over the so-called gay gene--reinvigorated Steve Cook's personal calling. Simon LeVay, a neurobiologist at the Salk Institute in La Jolla, announced that he had discovered a variation in the size of a part of the brain called the hypothalamus, which seemed to be smaller in gay men than in straight men. In the same year, researchers led by Dean Hamer at the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Md., conducted two studies in which they studied 76 gay men and 40 pairs of gay brothers. The researchers discovered a genetic marker on a section of the X chromosome which seemed to be passed down in families and shared by gay brothers. Marc Breedlove, a psychologist at UC-Berkeley, follows developments in human genetics and studies the effects of hormones on the development of animal fetuses. He says studies of identical twins--siblings with exactly the same genetic material--show that some sexuality can be inherited, because many share sexual orientation. Researchers at the Clarke Institute in Toronto have also discovered that birth order may have an influence on the sexuality of male offspring. The research is striking, and it suggested that the study of sexuality is a matter not just for the psychologists, but for biologists and geneticists as well. But the results were also misinterpreted. Unlike eye- or hair-color, sexuality is a complex trait influenced not only by genes, but also by environmental and possibly hormonal factors. Environmental factors--such as family dynamics and social conditions--may play a far greater role than genetics and help to explain why a baby boy born in New York City is more likely to identify himself as gay than one born in Des Moines. Researchers concede that genetic characteristics alone could never be used to predict sexual preference with certainty. Genes are but one clue in a very complex biological and environmental puzzle. Nevertheless, the discoveries produced headlines. Newsweek popularized the term "gay gene" by using it on its cover. Last May, the gay and lesbian news magazine The Advocate printed a photo of a fetus on the cover behind the headline "Endangered Species: This child has the gay gene. Will he be aborted because of it?" Weird Science ROBERT FOWLER, SJSU professor of biological sciences, says that the term "gay gene" is misleading. "All [Hamer] has found is a correlation between a sequence of DNA on the X chromosome and sexual preference," Fowler says. "He doesn't conclude that everyone who has this sequence is going to be gay. There is a tidbit of possibility that there may be a genetic disposition to male homosexuality, but no one is saying that it is a solid case, and that includes Hamer himself." Still, the first hint of evidence of a genetic link to homosexuality raised the panic that one day a test could be developed and that abortion would be used to de-select gay children. This is the primary concern of the 650-member Pro-Life Alliance of Lesbians and Gays (PLAGAL), an advocacy group based in Washington, D.C. Steve Cook is the vice president of PLAGAL and acts as its Bay Area representative. Joe Beard, a D.C. lawyer and PLAGAL's secretary, says the group is guided by two main concerns. "Number one," he says, "is the possibility of the discovery of a gay gene and the use of that information to eradicate gays and lesbians within the womb before they are born." "Number two," Beard says, "is the belief that when any segment of humanity is declared not fully human, this endangers the human rights of all humanity, whether it is lesbians and gays, Jews because of their religion or the unborn because of their stage of development." Beard believes the traditional alliance between the gay and lesbian community and the pro-choice movement is wrongheaded. "Many gays felt the concept of privacy expressed in Roe v. Wade logically extended to homosexual acts and that there was a legal connection between the right to abort a child and the right to make love to whoever you please," Beard says. The hatred expressed toward gays and lesbians by religious pro-life groups also drives them to the pro-choice side. "Groups like Feminists for Life and Americans United for Life are quite willing to work with PLAGAL," Beard says. "Others do not much care for us, like the actual leadership of the March for Life." However, even if a genetic test could be developed to determine a propensity toward homosexuality, the idea that such a test would ever be conducted on a pregnant woman defies common sense and violates the canon of medical ethics. No pregnant woman can walk into a hospital and ask to have a genetic rundown performed on her fetus. Prenatal tests are complicated, expensive and only performed if a doctor has a reason to suspect a problem. For example, women over 40 have a higher risk of bearing a child with Down's syndrome. For them, a prenatal test for that particular genetic condition may be appropriate. "It would not be ethical to engage in selection on the basis of non-disease-related characteristics or traits," assures Jeff Munson of the American Medical Association. "That kind of testing is simply not being done on fetuses." But the future of genetic testing is an ethical gray area. There are more than 4,000 known genetic disorders that can be predicted with varying degrees of certainty. There are genes associated with breast and lung cancer, schizophrenia, Alzheimer's and cystic fibrosis. Which tests should be performed and why? Who should know the results? Parents? Children? Employers? Insurance companies? "People are going to find genes that affect [disease] probability, and we as a society are completely unprepared to decide what to do," Breedlove says. Cook has already decided, and on various Saturdays he dons his sign and strolls along the Alameda in front of Planned Parenthood and sings, "Let there be peace on Earth and let it begin with me." In the second verse he sings, "Let there be peace in the womb and let it begin with us." This, he knows, puts him at odds with much of the gay and lesbian community. And though he is friends with some of the other pro-lifers who picket the clinic, he has to accept that the vast majority hate gays as much as they hate abortion. It's a lonely place, but he refuses to hide either identity to fit in. While abortion and genetics in fact pose little threat to gay fetuses, the prospect nonetheless gives Cook another reason to be out there. "I view pro-life as an extension of the peace movement," he says. "I sing so people know I come in the spirit of peace." [ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.