![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Movies Index | Show Times | San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Right on Target

Patrice Lecontes' 'Girl on the Bridge' balances the loss and luck of love

By Richard von Busack

FIFTEEN MINUTES into Girl on the Bridge, you know it's one of the year's best films. It begins with a close-up of the charming Adele (the pop star Vanessa Paradis). She answers questions, levelly, openly, even comically, about how she ended up throwing herself from a bridge into the Seine.

Adele outlines her life: getting picked up and getting dumped, and getting picked up again. She drifted into Limoges, one of France's most dismal cities. Even the judge trying her for whoredom was depressed by Limoges, Adele says, and so she did her best to make him feel better. Her monologue ends with a flashback to the bridge, where she stands, getting up the courage to drown herself. It's as if she's won the argument with her unseen questioners--she's proved that she's too unlucky to live.

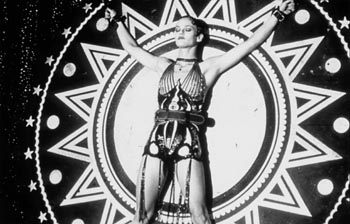

As she stands there over the water, a beat-up street performer named Gabor (Daniel Auteuil) starts trying to talk her out of it--dispassionately, using the intellectual approach, not the emotional one. Both end up in the freezing river anyway. They cheat death and, once they get out of the hospital, continue their conversation on a trip to Monaco and Italy and points east. Gabor is, as it turns out, a circus knife thrower, and the lithe, pretty Adele, who doesn't care much about her life, is the perfect human target.

It must seem a ghoulish story. In Gabor's company, Adele has an aura of luckiness powerful enough to turn a knife's blade: "It's not the thrower who counts, it's the target," Gabor says. These characters are too sane, too equal in power, to be reduced to terms like "sadist" and "masochist."

Director Patrice Laconte's urbane humanism shines over the give and take in this fanciful relationship. Laconte uses the sort-of romance between two circus performers as an illustration of how romantic love follows the laws of chance. In this breathless film, shot in ravishing widescreen black-and-white, the real subject isn't the old contrast between the grease paint and the suffering. What Laconte really likes is the tug of love--as opposed to a tug of war--between the man and the woman.

The ending of Girl on the Bridge seems too sweet; it makes me miss the strength of Laconte's finish for his 1990 film, The Hairdresser's Husband. In that film, the perfection of a love affair was perfectly sealed with death. What could have been a romantic cliche became a firmly argued point of view.

That kind of argument has been France's greatest gift to the movies. The elegant discourse between men and women flows into French cinema from French philosophy. In the best French movies, as in the best French writing, delicacy of feeling harmonizes with intellectual rigor.

This year's English art-house hit Croupier was fake cool--it gave its mostly male audience the usual lessons of film noir: dames are poison; a man can never let down his guard. That's not the kind of coolness and control I mean. Girl on the Bridge has Croupier's same atmosphere of night casinos and reckless impulse. Without being fatalistic, it stresses that a gambler's pleasures can never last, and that luck has to change.

Mostly, Girl on the Bridge urges the watcher never to be careless of good luck: "Learn to lose, or you'll take winning for granted." The film addresses that paradox: Who holds life lightly, holds it firmly. This paradox is as true about love as it is about life.

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![]()

Trouble in Paradis: Vanessa Paradis stars in 'The Girl on the Bridge,' Patrice Leconte's new film about the love between a knife thrower and his target.

Girl on the Bridge (R; 92 min.), directed by Patrice Leconte, written by Serge Frydman, photographed by Jean-Marie Dreujou and starring Vanessa Paradis and Daniel Auteuil, opens Friday at the Los Gatos Cinema in Los Gatos.

From the August 17-23, 2000 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.