![[Metroactive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Walk on The Wild Side

With enough stamina and ability to improvise, anybody can walk the whole of our coastline

By Richard von Busack

THIS GUIDEBOOK records an unsung feat. In 1996, the authors and their party walked the 1,150-mile length of the California coastline from Oregon to Mexico in an effort to chart the best border-to-border hiking trail.

Those who know and love the California coast will start wondering right away: How did they survive the car traffic? Can you go to the beach at the border of Baja California or does La Migra drive up in a jeep and push guns in your face?

Volume 1 of Hiking the California Coastal Trail already charted the way down the wild coast of Northern California. This conclusion takes the foot traveler through the more populated half of the state. Part of this trail runs through civilization of a sort: the densely populated beach towns of Santa Monica and the Orange County coast. Hiking there is just a matter of ambling down the shore.

But if you were to quit your job in Sunnyvale, strap on a backpack and start following the beach until you hit Mexico, you'd encounter more than a few obstacles on the way. The hiker has to travel past the nuclear power plants at Diablo Canyon and San Onofre, and the military bases at Vandenberg, Oxnard and Camp Pendleton.

The 1996 travelers were aided with sag wagons, but they still needed boats to get around breaks in the coast at Long Beach, Morro Bay and across the "severely polluted" Tijuana River. And parts of the coast are still pretty much as the conquistadors found them.

For example, take the 6 1/4-mile trek from Ragged Point to Piedras Blancas in northern San Luis Obispo County. The initial warnings in the chapter caution against high tides, rogue waves and security guards from the 77,000-acre Hearst Ranch, which owns the area. Here's the book's account of this leg of the trip:

I managed to get down to the beach north of Ragged Point by heading west for 1/4 mile, then descending a rough, steep path north, but once I reached the beach, the shoreline west and south was impassable and the shoreline north was only passable for 1/8 mile, 5/8 mile at minus tides. The Whole Hikers [i.e., the 1996 party] managed to follow a bluff-top path southeast through the pine forest, then bushwhacked to bluff's edge and scrambled down to the rocky beach, but when I tried to retrace their route in 1999, I got tangled in a huge poison oak thicket.

In the next few pages, the authors give almost algebraic directions for a better way of wending your way along the waterline to Piedras Blancas (motel, cafe, maybe a gas station). And while the California Coastal Act provided for public access to the entire coast of California, the same lack of official paths makes for similar bushwhacking: the book urges more permanent path markings.

I'M NOT A SERIOUS HIKER, myself, and count it as a special day if I make it up to the top of the granddad trail at a state park. But these two books bring the exciting news that some of the California coast is still remote and unsullied.

Even the beaches south of L.A., madly overdeveloped, include the less-crowded shores at Crystal Cove and San Onofre--the latter, probably less visited because people are still superstitious about Our Friend the Atom.

And if the cheese-box condos and industrial blight are depressing, there are also odd ruins along the way that remind us of the impermanence of developers' dreams. The book notes two strange Southern California sites.

One is the postapocalyptic abandoned housing track south of Playa Del Ray on a cliff under the runway at LAX. When I lived near there, it was a deaf ghetto. Only the deaf could live there without being driven nuts by the sounds of the jets. But even the deaf have left. It's amazing that no one's ever filmed a Mad Max movie there using the crumbling stucco ranch houses and overgrown sidewalks as a backdrop.

Farther down the coast, just past Point Fermin, lies a whole sunken subdivision from the 1920s that slid into the ocean when the cliffs gave way--the easiest possible metaphor for California hubris.

Sidebars discuss the coastal history along the way: the debate over whether Morro Rock is named "Morro" (Spanish for "promontory") or "Moro," because it was black as a Moor.

Hiking the California Coastal Trail also includes accounts of the attempts to reroute development by Heal the Bay in Santa Monica and to restore the Los Angeles River, currently held captive in a riparian minimum-security prison of concrete and chain-link fences.

This volume invites the reader to follow the path in its entirety and achieve something that will really stop conversation. Or the reader could do the walking in little pleasurable increments. The Whole Hikers made it, weeping, to the polluted sands at Border Field State Park, within sight of the seaside bullring across the international line. Who says Californians are underachievers?

This maddening state demands so much from its people. We're in thrall to the landlord or the mortgage company, obsessed with career calculation, subject to 10-hour workdays--we endure the crowds that are here, and fear the crowds to come. Add to these stresses the sense of impermanence--the knowledge that one good shudder of the earth could destroy it all. But as the book points out, with a little hiking off the beaten path, there's still the chance of being the only soul on a California beach.

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © 2000 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.

![]()

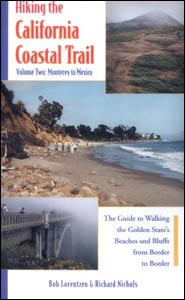

Hiking the California Coastal Trail, Volume Two: Monterey to Mexico

By Bob Lorentzen and Richard Nichols

Bored Feet Publications;

368 pages; $19 paper

From the August 17-23, 2000 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.